A Daughter’s Quest: On Anne Liu Kellor’s “Heart Radical”

Amy Reardon explores Anne Liu Kellor’s memoir about language, love, and belonging, “Heart Radical.”

By Amy ReardonNovember 12, 2021

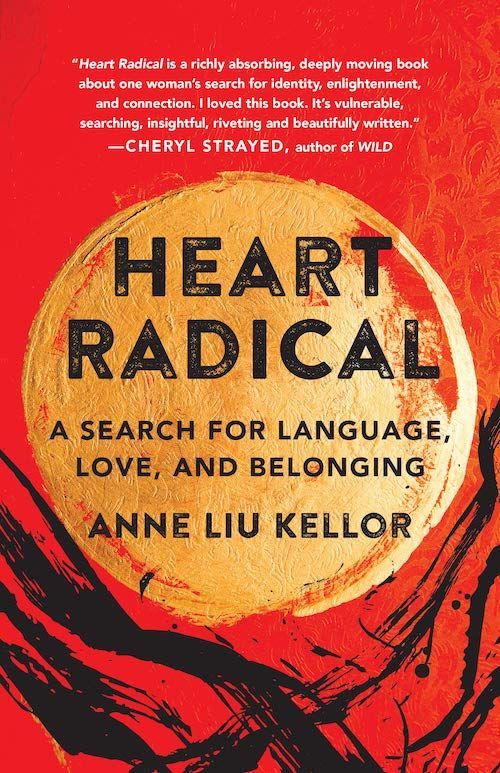

Heart Radical: A Search for Language, Love, and Belonging by Anne Liu Kellor. She Writes Press. 253 pages.

GROWING UP ASIAN AMERICAN in Seattle, Anne Liu Kellor struggled to understand the ache she carried inside. Her debut memoir, Heart Radical, tracks the author’s journeys to China and back home again in the late ’90s and early 2000s in search of her true self.

We meet Kellor after college, having become consumed with the need to learn the Chinese language and live in China. What she can’t seem to get her hands around is why. “All I knew was — I was filled with an intense longing and sorrow. Sorrow for the magnitude of suffering in the world, in China and Tibet, and within myself. Sorrow which I felt so clearly, but couldn’t understand why I felt so deep.”

There are clues. First among them, a general sense of opacity in her relationship with her mother, who immigrated from China as a girl, married a white man, and had two daughters. Also, there is this: “[N]or had anyone ever talked to me about what it was like to grow up multiracial — neither white nor fully Chinese, nor yet invited into a wider inclusivity as a person of color. Instead, everywhere I went, even at family reunions, I was simply reminded of my difference.”

Once in China, Kellor is immediately confronted with the grim realities of her limited language skills, widespread pollution, and her despair at a government that covered up the atrocities at Tiananmen Square. Just as she longs for deeper connections with others, she finds herself shutting down.

The same China where I witnessed a crowd in Chengdu pointing and laughing at the scene of a traffic accident, or where I watched a policeman kick over an illegal vendor’s cart full of apples and encourage bystanders to help themselves from the ground. The same China that is bent on getting rich and forgetting the past, watching out for one’s self at the expense of all others.

Kellor’s self-doubt is universally relatable, for who among us hasn’t yearned for faraway adventures only to arrive in a promised land and have our resolve immediately tested? “Maybe I’m too sensitive to live here for long, too permeable, too weak,” Kellor writes. “If there is an inner peace that I can cultivate wherever I am, I have not yet figured out how. I still have so much to learn about how to take care of myself. How to trust in what my body tells me I need.”

Which brings us to what’s most admirable about this memoir, and why Heart Radical is a timely read: its insistence on rejecting the same old, tired answers for complex questions that deserve more serious excavation. Kellor refuses to settle for uninterrogated expectations from parents and the culture. Which culture? Take your pick. American, Chinese, immigrant, religious, trauma, youth, academic. And then there’s my favorite aspect of this character’s journey. Like the best literary heroines, Heart Radical’s protagonist declines again and again with each new turn of the story to be subsumed by the men she meets in her travels. Even in the confusion and darkness that guides much of her odyssey, this self-professed quiet, heteronormative good girl nevertheless listens until she can hear her body and mind. To do so, she leans on her senses, on art, literature, dance, meditation, and mostly language. This writer digs until she finds and exposes that deeply human hum.

Her prose is at its best in the story’s most vulnerable moments.

In the morning, Yizhong and I wake late, snuggling in close like nesting rabbits, the air cold on our cheeks. I burrow in deep and breathe in his smell, a smell that somehow reminds me of my mother, something like peas. Maybe it’s a Chinese smell, or just skin and hot breath, the smell of someone else’s body.

In Heart Radical, the acquisition of language is a proxy for self-knowledge. When Kellor’s ability to communicate is stripped to only the essentials, she is forced to take a stand on questions on which she might vacillate if she had her native English to lean on, as with the choice to leave a Chinese lover. “I still love you, but my spirit needs more,” she says in Chinese. Indeed, the book’s title comes from the author’s language studies, her act of collecting words to describe her own heart.

One of the book’s sweetest scenes finds Kellor and a new friend, an artist she meets in China, giggling in the dark of their shared hotel room as the two young women exchange the English and Chinese words for body parts. “Now repeat after me, stress on the second syllable so you don’t confuse the two: Penis. Peanuts. Penis. Peanuts.”

The narrative choice to look back from middle age at her travels 20 years ago brings an important complexity that works to pull the story forward. A creative writing professor, Kellor seems to understand this, and it is her expert framing of her younger self’s search for her true nature through the lens of language acquisition that forms the book’s spine. The most charming among these tensions are the contradictions. For amid moments of despair, there are lyrical moments, like a sacred walk in Tibet. “I breathe in and feel my senses ripen; I exhale, grateful to be alive. Alive, alive, I am alive. I trust that I am guided, and I know I guide myself. Gravel presses indents into the soles of my shoes. Air brushes tiny secrets across the surface of my cheeks.”

Skillfully, Kellor threads the revelation of family secrets that ultimately will ease her protagonist’s angst and address the book’s central questions. “For years I’ve gone on, restraining, withholding. Yet the more I’ve learned to reveal, the less I can bear to hide. I am tired of being the quiet one, the one who bites her tongue to preserve the peace, to avoid the discomfort of confrontation.”

Heart Radical travels three continents in search of some person or place with answers, only to find them inside its protagonist, as we read in the book’s opening pages. “Now, there is still so much I do not know, but I do know that we each have an essential nature. And that it is our job to listen to that nature and figure out how to work with it, not how to become someone we are not.” With this memoir, Kellor has made a unique and tender contribution to the conversation about what it means to be fully alive.

¤

LARB Contributor

Amy Reardon’s work has been featured or is forthcoming in The Believer, Electric Literature, The Rumpus, Glamour, Adroit Journal, and The Coachella Review, among others.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Shocks in China That Were Heard (and Not Heard) Around the World

Lev Nachman on two books about China in the 1980s: Isabella Weber’s “How China Escaped Shock Therapy” and Jeremy Brown’s “June Fourth.”

The Complicity of Home: On Kazim Ali’s “Northern Light”

“Northern Light” is a mixture of memoir and environmental nonfiction that plays with the conventions of both.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!