A Close-Up on Iranian Cinema: On Godfrey Cheshire’s “In the Time of Kiarostami”

Abe Silberstein reviews Godfrey Cheshire’s “In the Time of Kiarostami: Writings on Iranian Cinema.”

By Abe SilbersteinJune 8, 2023

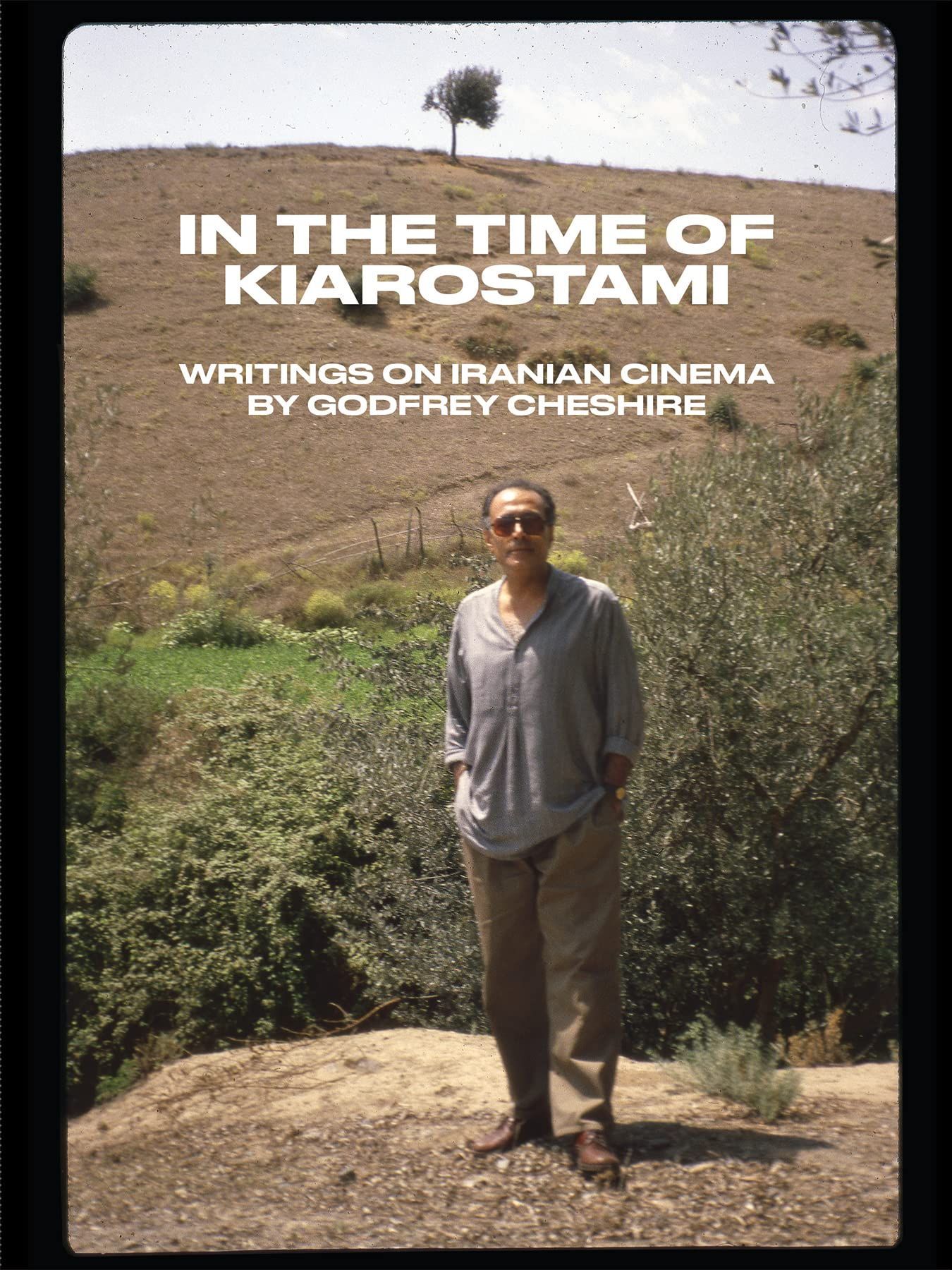

In the Time of Kiarostami: Writings on Iranian Cinema by Godfrey Cheshire. Film Desk Books. 309 pages.

IN THEORY, a fundamentalist religious dictatorship should not be a hospitable environment for an extraordinary artistic flowering whose treasures continue—four decades later—to please, confound, and reinvent themselves to audiences around the world. Yet this seems to be exactly the case with Iran’s cinematic output since 1979, when Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and his followers consolidated power in the wake of the Shah’s departure. (The Shah was himself a tyrant, but of the kind who sought to project a modern and art-friendly image.) We are all familiar with artists, writers, and filmmakers circumventing official and de facto censors to produce subversive masterpieces. But the consistency of Iranian cinema’s march across the world stage over the last 30-plus years suggests that something more powerful than individual creativity is at play—rather, a kind of relentless cultural force inexorably punching through whatever obstacles an authoritarian government places in its way.

The movies did not come especially late to Iran, nor was there a shortage of talented auteurs. This makes it all the more astonishing that so much of the international acclaim for Iranian cinema came after the establishment of the Islamic Republic. This artistic space was occupied by the most celebrated (at least in the West) of Iranian filmmakers: among others, Abbas Kiarostami, who died in 2016; Mohsen Makhmalbaf; Bahram Beyzai; Dariush Mehrjui; Jafar Panahi; and Asghar Farhadi, who in recent years has twice won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, putting him on a short and highly distinguished list with Akira Kurosawa, Federico Fellini, Vittorio De Sica, and Ingmar Bergman.

That information about Farhadi is a throwaway fact I learned while reading In the Time of Kiarostami: Writings on Iranian Cinema (2022), film critic Godfrey Cheshire’s account of his decades-long association with Iranian films. Born and educated in North Carolina, Cheshire moved to Greenwich Village in 1991 to write for The New York Press, at the time the main competition to The Village Voice for readers of Gotham’s alternative weeklies. Serendipitously, this was also around the time Iranian films began to crop up on the festival circuit and garner critical notice. Few of those observers, however, were as smitten as Cheshire, who went on to visit Iran seven times and become personally acquainted with some of the giants of Iranian cinema, including Kiarostami—whom he describes on the dedications page as a “phenomenal artist, inspiration, and ever-generous friend.”

Engagement with Kiarostami, who is today virtually synonymous with the movement known as the New Iranian Cinema, comprises the largest and most substantive section of Cheshire’s book. It is preceded by two autobiographical chapters on the author’s involvement with Iranian cinema, original writing as well as republished journalism, and followed by a too-brief treatment of other Iranian filmmakers via previously issued reviews and conversations. Still, In the Time of Kiarostami is a worthy and insightful companion for those looking to climb the heights of Iranian cinema, a journey on which scaling Mount Kiarostami is simply unavoidable and undoubtedly for one’s betterment.

¤

The author’s admitted lack of critical distance from Kiarostami is not so much a problem as it might seem. Cheshire, along with a handful of other alt-weekly critics like The Chicago Reader’s Jonathan Rosenbaum, was an early champion of the famed Iranian director long before their friendship began, and his initial euphoric feelings have long since been vindicated. However, this discovery of Kiarostami was only “early” in the context of international film criticism: by the early 1990s, he had been making films for a little over 20 years, starting as a house director for the state-run Center for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults (known colloquially in Persian as “Kanoon”). Kanoon, founded with the support of Queen Farah Pahlavi, was a redoubt for left-wing artists, including filmmakers associated with the Iranian New Wave (roughly 1963–74). Kiarostami’s career spans the Iranian New Wave, the tumultuous revolutionary period, and the New Iranian Cinema, but he first came to the attention of international critics with the release of Where Is the Friend’s House? (1987), perhaps the most sublime film ever made about childhood, which would become the first entry in his unofficial Koker trilogy.

Kiarostami was not one to make overtly political statements, in his films or in public commentaries. One major exception was First Case, Second Case (1979), his first film following the ouster of the Shah. This short work displays the ideological contradictions of postrevolutionary governance—when the act of defying authority, the very impulse which birthed the new regime, is criminalized. First Case, Second Case presents its argument as a classroom parable, in which a teacher removes an entire row of students from class because one of them repeatedly makes disruptive noises under the desk. In the first episode, one student decides to break this solidarity so he can return to his seat; in the next, the students leave the room and resolve not to betray the guilty student, even though it would allow them to reenter class.

Prior to showing the finales of the scenarios in First Case, Second Case, Kiarostami records interviews with the parents of the children playing the students, a diverse group that includes retirees, manual laborers, an accountant, and a navy colonel. What would they want their children to do? The answers vary but all center on whether the lesson of solidarity is worth more than a week of school.

Following the enactment of each finale, Kiarostami turns to prominent writers, experts, community leaders, politicians, and clerics to comment on the students’ choices. Most are sympathetic to the students who refuse to name the disruptive student and even condemn the teacher for practicing collective punishment. On these remarkable scenes, Cheshire writes: “Such anti-authoritarian views coming from the authorities themselves would have been unimaginable a few months before and would be so again a few months later—a prognosis that, as it turned out, was confirmed by the career of the film.” Fittingly for a film exposing the anxieties of a new political era, First Case, Second Case was first honored with an award and then totally banned (even for international export) by the young Islamic Republic.

Like the revolution itself, First Case, Second Case serves as a transition work from one period of Kiarostami’s career to another. In the decade before the revolution, Kiarostami directed four feature films, all of which are thematically rich and skillfully crafted but do not leave a distinct mark on the Iranian cinema of their time. They were squarely in the tradition of the Iranian New Wave, a realist cinema best exemplified by The House Is Black (1963), a raw 20-minute exploration of a leper colony by the poet Forugh Farrokhzad, and Dariush Mehrjui’s The Cow (1969), which placed the social deprivation experienced by rural Iranians in stark, psychologically harrowing relief. (The latter film angered the Shah’s government but found a crucial admirer in Khomeini.) In part inspired by the Italian neorealists, these films sought to lay bare the social inequalities and economic injustices of the Shah’s Iran. The failure of the 1979 revolution to resolve these inequities serves as a running theme in the succeeding New Iranian Cinema, a cinematic “wave” that continues to this day.

In isolation, the same perhaps is true of Where Is the Friend’s House?, Kiarostami’s first fictional work after First Case, Second Case, and the first in his Koker trilogy. But it was also the beginning of a legendary run of films that would help define what was most intriguing about the New Iranian Cinema, at least for viewers outside Iran—a critical distinction because, as Cheshire relays, Kiarostami in his lifetime was seldom viewed domestically as the country’s best director. His reputation in the West largely rests on six films he made between 1987 and 1999: The Koker trilogy, Close-Up, Taste of Cherry, and The Wind Will Carry Us. During Kiarostami’s meteoric rise, it was not uncommon to hear him dismissed by Iranians at home and in the diaspora as a festival director indifferent to the desires of Iranian cinemagoers. There are echoes here of criticism made of Kurosawa, whose films were thought to reflect more what a Western audience wanted to see in Japanese cinema.

In the book’s most perceptive essay, Cheshire makes two requests for admirers and detractors of Kiarostami’s work during this time, which he calls the “Masterworks Period.” To those who have judged Kiarostami’s work to be overrated or tedious, Cheshire implores them to “realize that the order in which you approach the films is crucial to how you understand them. Above all, view the Koker Trilogy in sequence, as a basis for watching the other films.” To the enthusiasts, he implores they go beyond placing Kiarostami within the context of Great International Auteurs and instead locate his work within Persian literary culture—in other words, to momentarily resist the urge to universalize the director’s work.

Having entered Kiarostami’s masterworks oeuvre at the wrong place myself, the first piece of advice struck me as quite sound. Clearly, Cheshire was prompted to offer it by the polarizing response to Taste of Cherry at the 1997 Cannes Film Festival. Though that film ended up sharing the festival’s top prize, the Palme d’Or, it earned the jeers of certain critics and viewers who disliked this slow-moving account of a suicidal man traversing the outskirts of Tehran in search of someone willing to bury his body. Leading this pack was Roger Ebert, who called Taste of Cherry “excruciatingly boring.” Cheshire attributes this reaction to those critics not putting the film in its sequential and cultural context. (In fairness to Ebert, as Cheshire notes, he did add that Taste of Cherry generated many fascinating movie reviews—an indication that the late Chicago Sun-Times reviewer was really stating what he believed art films are for, rather than simply panning Taste of Cherry.)

To begin with the Koker trilogy is probably the best choice for the initiate, but it also helps to go in understanding how this unintended trilogy plays with temporality, genre, and form. Where Is the Friend’s House? is an affecting film about a child looking to return a notebook to a friend who lives one town over. The boy’s journey from Koker to Poshteh and back evokes for me the dramas of childhood that seem trivial in retrospect but once colored my entire world. Where Is the Friend’s House? unashamedly inhabits the child’s perspective, and Kiarostami shows that these experiences are as profitable a basis for good art as any other. For an artist operating under the Islamic Republic’s gaze, sometimes with its critical support, childhood also offers important narrative possibilities. If done less explicitly than in First Case, Second Case, student-teacher interactions can serve as a relatable demonstration of the capricious and unjust use of authority.

Where Is the Friend’s House? is the only entry in the Koker trilogy that resembles a conventional movie. The following two films, And Life Goes On (1992) and Through the Olive Trees (1994), were made in the wake of the 1990 Manjil–Rudbar earthquake, which killed an estimated 50,000 people and left many more injured and homeless. The villages featured in Where Is the Friend’s House? were hit especially hard. Coming a mere two years after the end of the devastating Iran-Iraq War (1980–88), the earthquake exacerbated the pain and suffering rural families in Northern Iran were already enduring. Since Kiarostami seldom employed professional thespians for his films based in Iran, the actors in the film were drawn from the population of the villages, people directly affected by the disaster. In And Life Goes On, an actor (in real life, an unassuming economist whom Kiarostami encountered) playing Kiarostami returns to Koker and Poshteh with his son to find out if the cast members from Where Is the Friend’s House? survived. In Through the Olive Trees, another actor (this time a professional, Mohammad-Ali Keshavarz) plays Kiarostami, now reenacting the filming of And Life Goes On.

Watching these films as bodies continue to be excavated from the February 2023 earthquake in Turkey and Syria, the latter similarly pre-ravaged by man-made cruelty, it is impossible not to be moved by Kiarostami’s refusal to separate cinema from its participants. We are already emotionally invested in the characters of Where Is the Friend’s House? and, in And Life Goes On and Through the Olive Trees, we now care for them as people. Kiarostami’s simple humanity might be the skill most evident in these sequels. It is also, however, easy to understand why some Iranians at the time saw these films as exploitative, despite appearing to international audiences as overwhelmingly empathetic.

Intensely self-critical and autobiographical, Kiarostami would go on to make a film in 1999 (The Wind Will Carry Us) about a news-crew director visiting a rural Kurdish village in the hopes of filming their rustic funeral rituals. Is this a thinly veiled alter ego contending with the dark ambulance-chasing underbelly of the filmmaker’s art? As Cheshire writes, “Kiarostami leaves numerous gaps in the film’s surface that invite, even demand, our imaginative participation.” There are various other autobiographical and symbolic readings of Kiarostami’s work, which Cheshire explores. But the director’s idiosyncratic style casts an interminable, enigmatic shadow over his output—one reason why his films provide a hefty return on repeated viewings. There are always new layers to uncover, hitherto unseen symbols to be interpreted and subsequently reinterpreted. Reducing a Kiarostami picture to a specific theme or two (or worse, “morals”) is as futile as doing the same to one’s own life.

In addition to the natural disaster that provoked And Life Goes On and Through the Olive Trees, those films also reflected new artistic preoccupations for Kiarostami that arose with Close-Up (1990). In simple terms, Close-Up tells the story of a con man who convinces a stagnant upper-middle-class family that he is the socially conscious and politically audacious Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf. Makhmalbaf is, of course, a real person—and so is this story. But to say it is “based on a true story” would undersell its genius, as Close-Up itself became very much part of the story and has long since overtaken the events it supposedly depicts. Remarkably, Kiarostami secured the agreement of virtually everyone involved—Makhmalbaf, the fake Makhmalbaf (Hossain Sabzian), the victimized family, and the judge assigned to the case—to participate in the film. A bold mixture of reenactment, documentary footage, and a wonderfully staged climax, Close-Up was a complete departure from anything Kiarostami had done before and put him on a path of gutsy experimentation that would continue until his death in 2016.

To return to Cheshire’s second note on “reading” Kiarostami: if the order of watching Kiarostami’s films is critical in grasping their surface meaning and formal qualities, it takes a more serious engagement with Persian literature and history to apprehend his films’ cultural grammar. Cheshire writes,

Ultimately, the more one knows of their context, the more one realizes that Kiarostami and other Iranian directors need to be understood not so much in terms of Antonioni and Tati, say, but of Ferdowsi, Hafez, Sanai, Rumi, Ibn Arabi, Mulla Sadra, and other remarkable figures who share and illuminate their cultural lexicon.

Cheshire, who admits to a shaky relationship with the Persian language, relies on scholars such as Henry Corbin, a 20th-century French Iranologist, to provide a basis for cultural interpretation, as well as extensive dialogues with Iranian artists and scholars. Cheshire particularly focuses on Kiarostami’s engagement with Sufism and how faith interacts with even more ancient Persian concepts drawn, in turn, from Zoroastrianism. To demonstrate these presences of Shiism, Persian poetry, and other culturally specific forms, Cheshire wisely chooses The Wind Will Carry Us as a case study. It is one of Kiarostami’s more difficult films, profuse in local references not immediately accessible to even the most attentive Western cinephile. It will be intriguing what specialists make of these cultural and historical readings, and one hopes In the Time of Kiarostami will hasten the publication of more academic literature on this subject.

¤

While Kiarostami receives by far the most coverage of any director in the book, other major figures are not totally overlooked. Keen observations on the work of Makhmalbaf (as well as his daughter Samira), Mehrjui, Farhadi, Amir Naderi, Beyzai, and Panahi are threaded throughout. But it is only Kiarostami who appears to merit an extended analysis in a dedicated chapter of his own. This regrettable choice is mitigated by a solid and exhaustive index compiled by the book’s editor, Jim Colvill. Those making their way down the treasure-lined path of Iranian cinema will have no difficulty navigating the text in search of specific titles and individuals.

Indeed, one of Cheshire’s enviable skills as a writer is his ability to take decades of cinematic history and seamlessly tuck them into newspaper features and film reviews. His references to a director’s previous films, or their influences, never feel perfunctory or like exercises in flatulent name-dropping. Cheshire’s extraordinary access to Kiarostami as both an interview subject and a dear friend allows us to replace speculation with—whether fully factual or not—what the director wanted us to know. It is right to assume Kiarostami did not reveal everything, but he gave more than enough to appreciate every phase of his career, including a mystifying final work from 2017 (24 Frames). Viewers will likely struggle with several of Kiarostami’s films, as many critics did, but In the Time of Kiarostami hands us critical interpretive tools to appreciate them.

I began this review noting the not-so-peculiar coexistence of an oppressive government and a flourishing, internationally respected cinema. The ingenuity required of independent filmmakers looking to challenge audiences and critique the status quo is surely an important factor. Such Iranian films that make it through government approval naturally demand of the audience a greater degree of critical attention than was perhaps initially paid by the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance. But even that window is closing as the Islamic Republic confronts an existential threat: its own people.

In recent months, Iranians have taken to the streets in support of Women, Life, Freedom—just the latest sign of dissent the Islamic Republic has tried to crush. The filmmaker Jafar Panahi is now deemed so dangerous that he has been banned from working (and imprisoned several times, including for six months last year). The genius of Panahi’s most recent work, No Bears (2022), one of the best films of this young decade, clearly cannot be disentangled from the real-life persecution faced by its director. The art is extraordinary in large part because of the circumstances in which it was made.

Might this be why Westerners have become so fascinated with Iranian film in the last few decades—real and perceived qualities that denote a certain cleverness under pressure? If so, one should not evade the terrible discomfort brought on by “enjoying” such art. Still, understanding these films as a product of a rich Persian culture that predates the present authoritarianism offers a measure of relief, even hope. There will come a day when these works will be newly appreciated in an Iran free of theocracy and dictatorship.

¤

LARB Contributor

Abe Silberstein is a writer and critic based in Brooklyn.

LARB Staff Recommendations

My Lonely and Beautiful Country: On Nuri Bilge Ceylan

Kaya Genç analyzes the body of work of Turkey’s foremost contemporary filmmaker, Nuri Bilge Ceylan, through the lens of a recent academic monograph.

Hong Sang-soo’s Dream Time

On Hong Sang-soo's "The Day After" and the filmmaker's place in slow cinema.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!