A Boy Is Beautiful: On Edgar Gomez’s “High-Risk Homosexual”

Trey Burnette reviews Edgar Gomez’s debut memoir, “High-Risk Homosexual.”

By Trey BurnetteJanuary 11, 2022

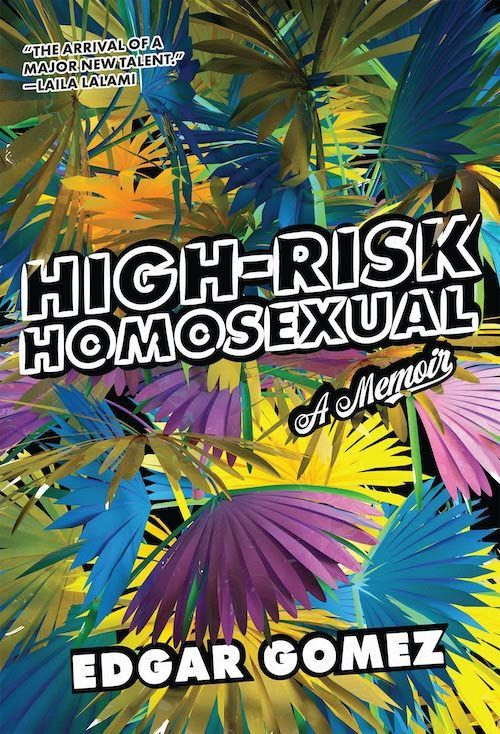

High-Risk Homosexual by Edgar Gomez. Soft Skull. 304 pages.

GROWING UP IN “The City Beautiful” of Orlando, Florida, is not easy for a femme-queer-Latinx boy of Nicaraguan and Puerto Rican heritage who has no safe space to express his beauty. However, Edgar Gomez’s High-Risk Homosexual sashays and shantays readers through the author’s teenage years and into his early 20s. In this debut memoir, the author explores “a world desperate to erase [him].” A place where queer Latinx men need pride for survival, but also where that pride can be toxic. Like a night out in Manolos, High-Risk Homosexual brings both pleasure and pain, and readers are lucky to be invited to this coming-of-age ki-ki.

The story begins with 13-year-old Gomez and his mother visiting her brothers in Nicaragua, where cockfighting and sex with a woman are supposed to turn Gomez into a man and stop him from being a “malcriado.” He returns to Orlando, still a boy, accepts his gayness, comes out to a few people, meets queer friends, and explores his identity. He makes his way to college, moves out of his mom’s house, strips on a stage with drag queens, and meets men at a bathhouse. He is greeted with both love and hostility during his exploration of himself. Eventually, Gomez lands in California, finds himself in a doctor’s office, in the backseat of a car, and in graduate school, still grappling with his fears.

As Gomez and his mother ride through the streets of Nicaragua in the backseat of a cab, heading to the airport for his mom’s return home, Gomez reaches into her purse, removes her press-on nails, and playfully applies them to his fingertips. His amusement triggers a scornful look from her. He pleads that he is “just messing around.”

“Well, it’s not funny. And your tios won’t think so either,” his mother warns. She has caught her son being a “bad boy” before, mimicking Britney Spears and wearing her dresses. Gomez is aware of all his desires, but as his family conspires, he unwillingly remains with his uncles, who attempt to indoctrinate him into their “machismo” version of manhood. Gomez finds himself locked in a room with a “girl-woman” where he must lose his virginity and something entirely different. “How long does it take for a boy to become a man?” the writer asks. Luckily, Gomez befriends a group of transgender sex workers, and these ladies tell him, “You know you’re perfect, right?”

As the story progresses, Gomez ignores his family’s spoken and unspoken suspicions and shaming of his masculinity and betrayal of their testosterone-fueled mandates. Of his mother, he writes, “I never answered her, because to speak would have been to acknowledge that I could hear, which would have meant that I’d heard them. If that were true then I couldn’t tell myself they didn’t know my secret. Everything would be okay as long as I kept quiet.” As the narrator gains a greater awareness of himself, he also diminishes himself to survive. That shrinking compounds Gomez’s sadness and further isolates him from his family, but his silence also serves to protect him. Gomez’s pain is felt in the narrator’s silence and in words unwritten. Gomez captures a truth for many LGBTQ+ youths: ignore the hate, silence your secret, and you may survive. But the narrator begins to break his silence and live beyond mere survival.

High-Risk Homosexual creates a safe space where Gomez navigates through the hostile world that wants him to be someone other than himself. Among the most beautiful scenes in the book is one in which the narrator finds his tribe. Gomez meets drag queens at a club, and he registers that they have found their safe place; he writes: “They found a place in their minds where it was okay to be sexy, where they were safe, and they carried it with them.” With the queens, Gomez begins to find what he is looking for: “For now it was enough that we were together in a place where we could be whoever we wanted to be and to hope that someday we could summon this feeling again.”

Gomez, the character, moves between two contradictory worlds, one where he shrinks and one where he expands, deciding how and when to be visible in his relationships with people and places. As narrator, he puts the sissy in the walk with candid, funny, and sometimes heartbreaking prose about his relationships. When Gomez comes out to his mom, she loves him and also shames him for what she fears: his homosexuality and her presumption that he will eventually die of AIDS. Gomez’s brother loves him, but Gomez never tells him he is gay. The limits of their relationship are fully elucidated when, after the Pulse nightclub shooting, Gomez’s brother does not reach out to check on him. Gomez writes, “Him reaching out to me would have been a breach in our unspoken contract about not discussing my sexuality.” Again, the characters quietly choose not to acknowledge his queerness, and Gomez’s sadness is expressed in what is not said. The shame, irrational fears, and tacit knowledge of the book’s characters are universal to many members of the LGBTQ+ community, both inside and outside the Latinx community. Fear of being an outcast or unlovable can lead to one’s unfulfilled self-actualization, often presented as anger or depression, and seen frequently when questions arise on Gomez’s journey.

Silence is Gomez’s familiar protector, especially regarding racial prejudices and pressure to embrace gender conformity, even within the LQBTQ+ community. He dresses in butch drag to retain a boyfriend’s affection and remains quiet about his femme identity. He plays into society’s stereotypes of Latinos “as savage and sex-crazed.” He writes, “Listen, I never told Eric I was masculine. I just didn’t say I wasn’t.” When Gomez does come out as femme, the boyfriend dumps Gomez from his “no fats, no femme” world.

In one of the book’s most contemplative passages, the narrator considers the consequences of homophobia for Omar Mateen, the Pulse nightclub killer. While holding Mateen accountable for his actions, Gomez writes, “I’m disturbed by the similarities we shared as teenagers.” The two lived near each other, struggled with their sexuality, and had immigrant families who held homophobic beliefs. He concludes: “In retrospect, it’s a miracle anyone ever comes out of the closet, considering all the ways the world tells queer people to deny ourselves.” Gomez knows he must take pride in his identity because he has seen the most disastrous effects suffered by someone who couldn’t accept his identity: rage and death.

Gomez’s memoir werks it and serves the tea with humor while addressing serious issues; therefore, the reader is not overwhelmed with sadness. His scenes involving drag queens, casual sex, moving out, and higher education constantly entertain, as when he ventures into a bathhouse, where he learns the rules are “[n]othing [he] hadn’t already learned from [his] mother.” Wash your hands. Gomez realizes, wherever he goes, clothes on or off, people are trying to heal their sadness with love.

In the title chapter, toward the book’s end, as Gomez becomes more eager to experience the physicality of his sexuality, he visits a doctor for a prescription of PrEP (Truvada). After seeing the medical insurance code “high-risk homosexual” on his paperwork, he struggles with feeling stigmatized. Angry and confused, Gomez asks if heterosexuals go through the same scrutiny. His anger grows when his shame intersects his queer identity and Latinx heritage. Gomez remembers being told to use the disadvantages of his immigrant status to get help with his college applications. And now, he is being told to use the obstacles of his sexuality to help him with a prescription. He writes, “I couldn’t help resenting what I believed I had to do to accept it, which was to take those things I’d slowly begun to take pride in — my queerness, my family’s migration — and claim they’d put me at a disadvantage.” Gomez tethers the universal dichotomy of marginalized people: what oppresses one also helps one rise. What brings shame also brings pride.

In High-Risk Homosexual, Edgar Gomez “long[s] for a guide to teach [him] how to navigate being a queer Latinx man.” But he slays and pieces together his own path while searching for a sense of belonging, agency, and a safe space to express his identity. Gomez’s vulnerable and humorous voice gives strength to High-Risk Homosexual. And yes, while this highly personal memoir is written through the unique lens of a femme-queer-Latinx, there is a universal narrative that will resonate with anyone who has ever felt marginalized. No matter how we identify or where we end up, ultimately, we are all high risk, and Gomez captures this universality so well. Shantay.

¤

LARB Contributor

Trey Burnette is a writer and photographer with a BA in psychology from the University of Southern California and an MFA from the University of California, Riverside. He studied comedy writing with The Groundlings and The Second City in Los Angeles. His work has been featured in The Kelp Journal and NBC News, and he served as nonfiction editor for The Coachella Review.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Trying to Build the World from Ash: Chris Rush on the Art of Memoir

Grace Hadland interviews artist Chris Rush about his new memoir, “The Light Years,” which details his coming-of-age as a gay man in 1970s suburbia.

Of Fairylands, Borders, and Charmed Circles: On Julio Capó Jr.’s “Welcome to Fairyland: Queer Miami before 1940”

Carlos Ulises Decena finds a welcome, nuanced portrait of queer history in Julio Capó Jr.’s “Welcome to Fairyland: Queer Miami before 1940.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!