A Portrait of the Young Girl: On the 60th Anniversary of "Lolita" Part I — An Interview Series

By Erik MorseJanuary 6, 2015

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2015%2F01%2FLolita-Cover.jpg)

Left: Olympia Press’s two-volume edition of Lolita as part of its nondescript “The Traveller's Companion Series,” 1955.

- Part I: Lara Delage-Toriel

- Part II: Meenakshi Gigi Durham

- Part III: Lorelei Lee

- Part IV: Emily Prager

Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul. Lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta. She was Lo, plain Lo, in the morning, standing four feet ten in one sock. She was Lola in slacks. She was Dolly at school. She was Dolores on the dotted line. But in my arms she was always Lolita.

— Vladimir Nabokov, Lolita

It is through the Young-Girl that capitalism has managed to extend its hegemony to the totality of social life. She is the most rugged pawn of market domination in a war whose objective remains the total control of daily life and “production” time.

— Tiqqun, Introduction to Preliminary Materials for a Theory of the Young Girl

¤

AFTER NEARLY 60 YEARS, the character of Lolita, nee Dolores Haze, continues to hold court as the most notorious tween in American letters. Nabokov’s third English-language novel, provisionally titled The Kingdom by the Sea, Lolita was first published in 1955 by Maurice Girodias’s Olympia Press after numerous New York publishers rejected it for its explicit portrayal of narrator Humbert Humbert’s pedophilia. Although the Paris-based Olympia had the distinct honor of publishing semi-legal texts by Jean Genet, Henry Miller and William Burroughs, Girodias’s “blue” press (whose covers were in a nondescript green) was organized as and perceived by most as a porn publisher — lending Lolita its less than literary tenor. The book was subsequently banned in France, England, Australia and parts of the US. It was only published in the United States three years later when writers and critics like Graham Greene and Lionel Trilling publically offered their endorsements. (Trilling, perhaps incautiously, extolled it as a book “not about sex but about love […] It put the lovers, as lovers in literature must be put, beyond the pale of society”). In part because of its blacklisted status, by 1958 popular scuttlebutt had elevated the G.P Putnam’s Sons English edition to a bestseller and invented a new cultural archetype in post-War American literature: the nymphet.

As Barbara Churchill writes,

[T]he Lolita image has so pervaded popular consciousness that even those who have never read the book usually know what it means to call a girl “Lolita.” The moniker “Lolita,” translated into the language of popular culture, means a sexy little number, a sassy ingénue, a bewitching adolescent siren.

Ironically, it is because of her very prominent role as an erotic cipher that Lolita’s physical appearance — as Nabokov describes — has often been exaggerated or reinterpreted like an inexhaustible Rorschach. . Ephebophiles and media marketers have been typically as elated by the signifiers of “[a] disgustingly conventional little girl…Sweet hot jazz, square dancing, gooey fudge sundaes, musicals, movie magazines and so forth,” as Nabokov was repulsed by them. Indeed, through the highly subjective — and sociopathic, as some would claim — portraiture of Humbert’s erudite pervert, only a few basic, physical statistics of Lolita avail themselves to the reader. She is introduced as 12 years old, 4’10” tall and 78 pounds, with chestnut hair, brown skin, pale-grey eyes and lips the color of red candy. Several years younger than the teenage Lolita Sue Lyon portrays in Stanley Kubrick’s 1962 film adaptation, she never sported the heart-shaped sunglasses, freshly polished toenails, or dangling lollipop with which she became associated. Nor did she exhibit the kinds of hyper-sexualized, “jail bait” delinquencies that served as fodder for a half-century of school-girl pulp, porn, and mondo. She was prepubescent and pre-sexed — sex for her is an act that, according to Humbert, the child imagines to be “merely as part of a youngster’s furtive world, unknown to adults [and that] [w]hat adults [do] for the purposes of procreation [is] no business of hers.” It is only in Humbert’s purpled ruminations that Lolita attains the rarefication of the Grecian nymphet, which he characterized as “maidens who, to certain bewitched travelers, twice or many times older than they, reveal their true nature which is not human, but nymphic.”

Is this the image of the girl-child that has come to stoke the juvenescent lusts of decades of literati, as well as latter-day porn enthusiasts, whose internet metrics consistently place “teen” as the highest porn-related word and category search on Google?

In his 2008 study, Chasing Lolita, literary critic Graham Vickers explains, “Lolita was to become the patron saint of fast little articles the world over, not because Nabokov’s mid-1950s novel depicted her as such but because, slowly and surely, the media, following Humbert’s unreliable lead, cast her in that role.” In the aftermath of Lolita’s eroticization of the young girl, there remains a singular aura about her, largely because she inhabits one of the last taboos of which we do not speak — yet her likeness has saturated our daily perceptions of fashion, celebrity and youth culture. “She it was to whom ads were dedicated: the ideal consumer, the subject and object of every foul poster,” Humbert observes of his nubile “brat”’s vulgar taste in the American culture of the commodity. From victim to coquette to sex kitten to feminist and young girl, her star persists in differing generational guises of power, seduction and maturity. Among her sisters are Carroll Baker, Natalie Wood, Brooke Shields, Traci Lords, JonBenét Ramsey, Britney Spears, Miley Cyrus, Lana del Rey, and the nameless, near-naked vixens of countless Calvin Klein and American Apparel ads.

In this series, the Los Angeles Review of Books assembled a group of female authors, artists and performers who, dedicated to examining the faces, bodies and voices of the young girl, consider the significance of Nabokov’s pubescent protagonist as both a literary conceit and an object of patriarchal fetish. Among the many important themes and motifs they consider include these larger, crucial questions: Who precisely is Lolita and why are we awestruck in her presence? How have our perceptions of her changed since 1955? What does she look like now? Are we all guilty of objectifying the young girl? And why are we afraid to articulate the sex, passion and emotions of the contemporary nymphet?

¤

Lara Delage-Toriel is a professor of US literature and creative writing at the University of Strasbourg and former/founding French Nabokov Society president. Her current work focuses on the body in American literature, and she has written extensively on representations of women in Nabokov’s oeuvre. She is also the author of the bilingual text, Lolita de Vladimir Nabokov et de Stanley Kubrick.

ERIK MORSE: Do you remember when you first read Lolita?

LARA DELAGE-TORIEL: Lolita was the first of Nabokov’s works I read, when I was 19 or so. I remember noticing his Lectures on Literature, propped up high in our local library, some years beforehand, and associating the letters that made up his name with some remote area of knowledge, an islet to which I was denied access. Then one morning I found a boat. It was on the Parisian metro, on my way to the Lycée Henri IV. A classmate was immersed in Lolita and encouraged me to read it. I remember buying the book without daring to start it. I only did so a few months later, after I’d stumbled upon chapter 2 of Transparent Things in the course of a translation class: “As the person, Hugh Person (corrupted ‘Peterson’ and pronounced ‘Parson’ by some) extricated his angular bulk from the taxi that had brought him to this shoddy mountain resort from Trux, and while his head was still lowered in an opening meant for emerging dwarfs […]” I still feel the awkwardness of the position I’d been thrust into, an Alice in Nabokovland trying to coax her translator’s bulk into a hole cut out for crazy creatures. Only then did I feel ready to read Lolita.

What were your initial impressions, both of Nabokov’s story and the character of Lo? Do you recall how you first envisioned her before seeing other visual depictions?

I don't quite remember the exact impression either the novel or its eponymous character made on me. All I know is that I decided to launch into a Master’s Thesis on Nabokov just a few months later.

Though the original Olympia Press edition of Lolita had only a simple green cover — which was standard for their "porn" catalog — there have been numerous pictorial covers over the last 60 years. Is there any cover or edition that you think made a particularly lasting contribution to the iconography of the nymphet?

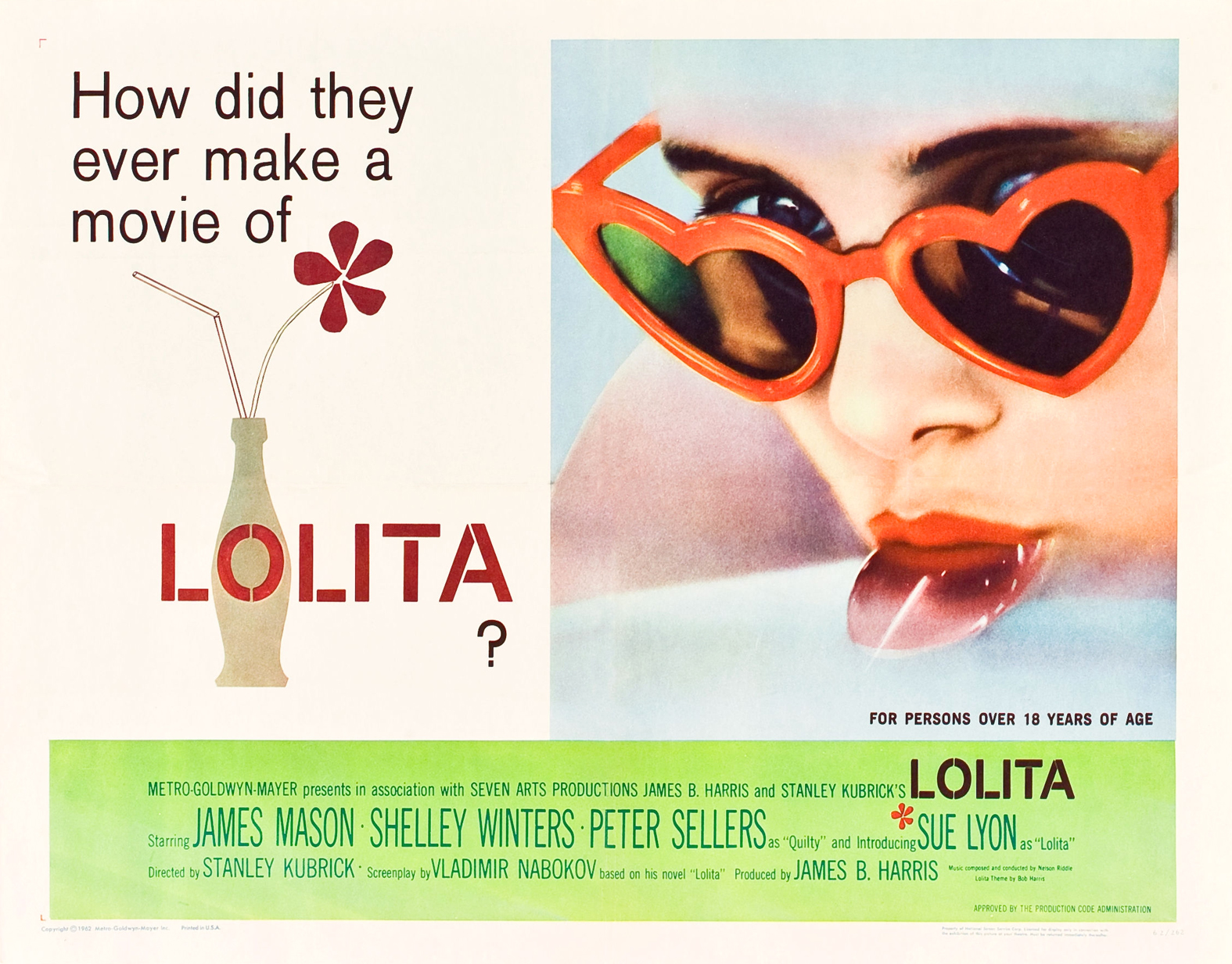

“There is one subject which I am emphatically opposed to: any kind of representation of a little girl,” wrote Nabokov to Walter Minton of Putnam’s, in 1958, when discussing the dustjacket for the first American edition of Lolita. In a certain way, therefore, Olympia Press was one of the rare publishers to offer an acceptable cover by Nabokovian standards. The iconography that has prevailed most often shows not a little girl, but a young woman. The representation that perhaps has left the most lasting contribution to Lolita’s iconography is the poster of Kubrick’s 1962 adaptation, which metonymically features Sue Lyon’s eyes peering at us through red heart-shaped glasses, a red lollipop between her red lips. I say “metonymically” because one of the chief attractions of this picture is its incompleteness, the fact that we are only allowed a fragment of the girl’s body, suggestive of greater riches to be mined. The actress’ alluring gaze places the reader or spectator in the same position as Humbert Humbert/James Mason, when he first discovers Sue Lyon lying in a bikini suit in her mother’s garden. We are made complicit in our voyeuristic desire as she makes us “salivate” for more. But most importantly, this picture inverts the novel’s initial power relationship: whereas Nabokov’s girl is constantly an object of gaze and desire, a prey whose voice and thoughts are most often smothered by the narrator’s overweening presence, here she clearly becomes a gazing subject, and therefore a much more active, self-conscious and potentially dangerous female.

MGM’s infamous teaser poster for Stanley Kubrick’s Lolita, with lollipop and heart-shaped sunglasses, 1962.

In an essay dedicated to the literary pictorialism of Nabokov, you write that "his art has too often been treated as a kind of rococo wedding cake, decked with delicate sugar flowers and sexy little girls — fantastically ornamental, indeed, yet hardly artistic, in the noblest sense." Nowhere is this more true than in Lolita, the only text of his to have captured the attention of the reading public, who seem ambivalent to label Nabokov as a literary "dirty old man" in the vein of Bataille, Lawrence, or Miller. What kind of influence do you think the specter of Lolita has had in depictions of femininity and girlhood in the literary arts?

The fact that Lolita has become a common noun — a linguistic process that goes by the name of antonomasia — indicates how widespread the influence of Nabokov’s nymphet has been. Shaped into a figment of our “collective representations” — to borrow a phrase by sociologist Durkheim — her image has most often been reduced to a certain type of female figure, “a precociously seductive girl” (Webster’s Dictionary). Accordingly, apart from Amy Homes’s controversial The End of Alice (1997), the various pastiches, parodies and winking allusions that have been spawned by Lolita draw less on the theme of child abuse than on the erotic appeal of a 14+ young girl who would qualify as “that horror of horrors” by Humbert’s book. No trace of tragedy remains in Steve Martin’s blithe story, “Lolita at Fifty” (1998) or Lee Siegel’s romance, Love in a Dead Language (1999). Since she is much less of a victim, the young girl gains in agency and the reality of her far from “innocent” teenage mind is foregrounded — particularly when the narrative is written from the girl’s point of view, as in Pia Pera’s Diario di Lo (1995), or Emily Prager’s Roger Fishbite (1999). In Frédéric Beigbeders’s Au secours pardon (2007), the largely quoted blog of 14-year old Lena reveals how sexually experienced she already is.

Do you think Nabokov has generally avoided the kind of public censure typically experienced by those writers/artists interested in childhood sexuality?

One tends to forget that public institutions and media in the 1950s did not welcome Lolita, although it soon turned into a bestseller and has since been canonized as a literary masterpiece. The reason for this critical endorsement is due to the fact that Lolita does little to satisfy the voyeuristic impulse and erotic gratification to which pornographic books generally cater. In order to appreciate the novel, readers need to wade through an extremely sophisticated text bristling with intertextual references, metaphors, puns, and metatextual patterns. The presence of an unreliable narrator — i.e. Humbert the pedophile — who admits he is a monster further thwarts any unmitigated form of identification with what little erotic fulfillment is actually described, essentially within the first half of the novel.

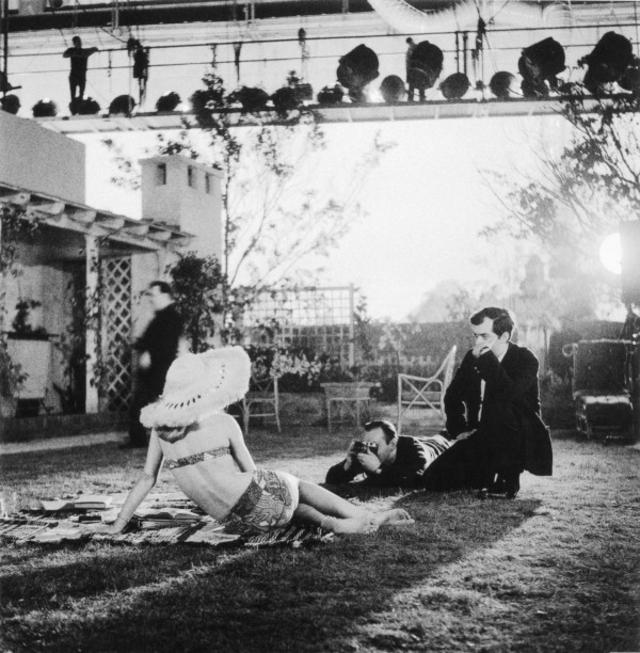

Reverse shot of Sue Lyon’s iconic pose on the Lolita film set. Included in the image: set photographer Joe Pearce and director Stanley Kubrick, c. 1961.

In Graham Vickers’s critical biography, Chasing Lolita, the author traces a wonderful cinematic history of the character of the precocious girl-child in American film, both prior to and after Kubrick’s adaptation of Lolita, from Shirley Temple to Brooke Shields. He points to the Tennessee Williams film Baby Doll as the primary example of film and rock ’n’ roll’s synergetic sexualization of the girl-child in the 1950s. In many ways Baby Doll’s Southern Gothic melodrama is the obverse of Lolita and yet was a much more radical onscreen exploration of sexuality. Can you speak a bit about how the culture and aesthetic of the 1950s, both in Europe and America, gave rise to this iconic shift in the sexualization of the young girl from what had come before?

Two important and interdependent trends might help us explain this “shift:” on the one hand, the prevailing Cold War ideology; on the other, the birth of a new youth culture after the Second World War.

America’s Cold War ideology was characterized by an anxiety-ridden rhetoric, which divided society, much like world politics, into simple binaries. Thus, in much the same way that communists threatened to penetrate the government, it was felt that sexually deviant individuals threatened to infiltrate American homes. As Estelle Freedman has shown, “each of the two major sex crime panics — roughly from 1937 to 1940 and from 1949 to 1955 — originated when, after a series of brutal and apparently sexually motivated child murders, major urban newspapers expanded and, in some cases, sensationalized their coverage of child molestation and rape.” According to Frederick Whiting, “the pedophile was considered the apogee and epitome of all sex criminals.” A striking illustration of this was featured in American Magazine (July 1947) by the picture of an enormous male hand looming over the heads of three girls, apparently between eight and 10 years of age, with an article by J. Edgar Hoover, the title of which could not be more explicit: “How Safe Is Your Daughter?” Of course, this kind of anxiety was not wholly new, but what grew in the 1950s was the presence in mass media of the teenager figure — and the teenage girl in particular — after the apparition of very young Hollywood stars like Shirley Temple in the 1930s and 1940s. Hence a double phenomenon arises: an urgency to protect the adorable child, but also a sexualized glamorization of youthful femininity, as seen by the increasing use of young girls as agents or objects of commercial baiting.

Against this backdrop of vulnerability, and hence control, emerged a new youth culture, seeking to free itself from suburban domestic standardization. One of its key representatives is Holden Caulfield, the main protagonist of Catcher in the Rye (1951), who wanders around Manhattan after he has been dismissed from school, and in the process pulls down all the idols of “phony” America. Another important role model for young people was furnished by James Dean, the “rebel without a cause” who gave youth a cause to fight for. Rock n’ roll and the Beat generation are also emblematic of this quest to find new idioms, codes, and territories in which to express an identity distinct from older generations. Humbert’s song makes quite clear the role played by rock n’ roll in allowing teenage girls and boys to acquire an autonomous space from which the parent is debarred:

Oh Dolores, that juke-box hurts!

Are you still dancin’, darlin’?

(Both in worn Levis, both in torn T-shirts,

And I, in my corner, snarlin’).

Leerom Medovoi has studied the way in which female teenagers also found within this context a space to carve out their own nonconformist identity, notably through the figures of the tomboy and the rough girl, as featured in films like Gidget (1959) and Girls Town (1959). Ironically, the nonconformism of youth culture was in fact absorbed by dominant ideology since it could serve as ammunition in America’s war against totalitarianism. In Lolita, Humbert seeks to conceal the traces left by his intercourse with a minor by suggesting “the abandoned nest of a restless father and his tomboy daughter, instead of an ex-convict’s saturnalia with a couple of fat old whores,” the former case appearing of course both more plausible and acceptable. Nabokov also mockingly evokes this absorption in a parodic scene featuring Miss Pratt, Beardsley College's principal, and her “progressive” theory of education. Concerned about Lolita's lack of sexual maturity, she gives Humbert a prescriptive account of youth culture's priorities: “Dr. Hummer, do you realize that for the modern pre-adolescent child, medieval dates are of less vital value than weekend ones [twinkle]?”

Either rightly or wrongly, it seems the lasting public perception of the character of Lolita has been due to Stanley Kubrick’s 1962 cinematic adaptation with actress Sue Lyon. In fact, the paradigmatic clichés we often associate with the nymphet — the heart-shaped sunglasses, the lollipop, the painted toenails — are not highlighted in the novel. So many of the subsequent fetishes and imageries that have become associated with the nymphet don’t seem to reside with Nabokov’s Lo, but with Kubrick’s. How did Sue Lyon’s portrayal of Lolita in Stanley Kubrick’s film emblemize or exaggerate a sexuality that had been absent in Nabokov’s text?

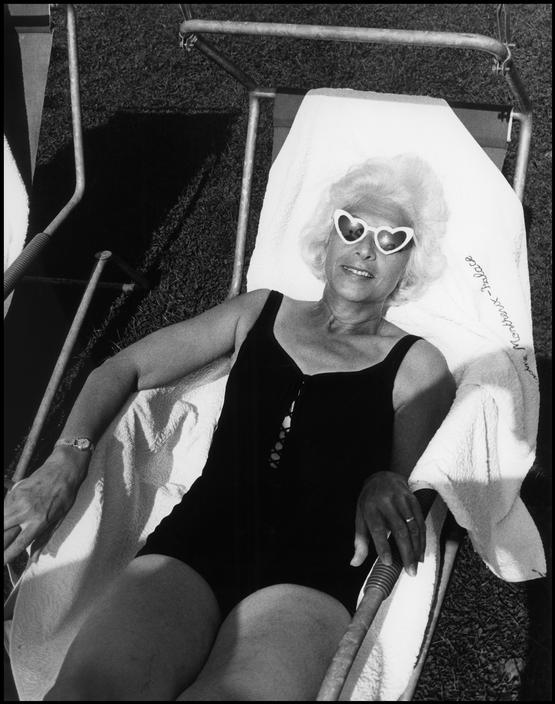

While I agree with you that Kubrick has greatly contributed to fashioning today’s perception of Lolita, I’d hardly say that sexuality is absent in Nabokov’s text, or that the paradigmatic objects we’ve come to associate with the nymphet were wholly invented by the filmmaker. I can think of a few basic facts about film as a medium that explain why Kubrick’s Lolita might give the impression of having created something entirely of its own: films are visual artifacts and most often last about an hour and a half to two hours. Since they’re visual, the objects they present (such as lollipops or heart-shaped sunglasses — the latter being in fact only used for the poster, not the film itself) can be immediately recognizable and reproducible. Surprisingly, although the Nabokovs pestered against the commercial distortions of the original nymphet, they did seem to endorse the heart-shaped prop, since a 1966 photograph shows Nabokov’s wife Véra smilingly wearing a similar pair of glasses (only they were white instead of red-framed) as she reclines in a bathing suit by the Montreux Palace Hotel’s pool. Thanks to its mimetic effect, film representation may thus strike a more immediate correlation with reality. And because a film is relatively short, it needs to concentrate and make a drastic selection of the information it’s going to show; this concentration acts as a kind of magnifying glass, making those objects that have been selected protrude.

Véra Nabokov lounging at Montreux Palace Hotel in Lolita sunglasses, 1966.

In comparison, novels can be much denser, their ingredients unfolding more leisurely over longer stretches of time, which makes it more difficult for their objects to become iconic. Lolita is however rife with artifacts which draw from popular culture: Cokes, sundaes, fudges, hamburgers — which, to Humbert’s dismay, have a much greater appeal for Lolita than Humbergers — comics, magazines, milk bars, chewing gum, and so on. More obviously sexualized items also appear in the novel, such as her lone white sock; the remnants of cherry-red polish on her toenails;; the “check weaves, bright cottons, frills, puffed-out short sleeves, soft pleats, snug-fitting bodices and generously full skirts,” which Humbert relishes; down to the nuances of swimsuits he has to choose from for his darling: “dream pink, frosted aqua, glans mauve, tulip red, oolala black.”

However, much of the allure of the nymphet lies in her elusiveness, in the narrator’s failure to fully depict and consume her: “I would like to describe her face, her ways — and I cannot, because my own desire for her blinds me when she is near. I am not used to being with nymphets, damn it. If I close my eyes I see but an immobilized fraction of her, a cinematographic still, a sudden smooth nether loveliness, as with one knee up under her tartan skirt she sits tying her shoe.” Humbert’s tartan evocation could have easily been a cliché, were it not for its fluttering fleetingness. Instead of cinematographically “stilling” and stealing images of the desirable girl, Nabokov makes them fluctuate within Humbert’s complex subjectivity, refracting them through “the prism of his senses,” and reflecting them in his very blood. The novel is hence permeated by the language of desire, with its incandescent curlicues: “What’s the katter with misses?” mutters Humbert the spoonerist as his kissing tongue runs amok. The suggestive playfulness of Nabokov’s prose allows him to be much more daring and subversive than Kubrick could ever be. One of the reasons for this is that although the latter had escaped from Hollywood, he still had to comply by current censorship rules, and thus had no choice but to turn the relationship between the stepfather and his protégée into something very chaste. Emblematic of this is the night in the Enchanted Hunters Hotel, which features James Mason not in bed with Sue Lyon, but trapped in a ridiculous cot, now a slapstick comedian instead of a Latin lover. Kubrick also chose to foreground the rivalry between Quilty and Humbert in order to steer his film towards the more politically correct form of the love triangle. So I’d say that Kubrick’s film does not so much exaggerate the sexual content of the novel as it transfers Nabokov’s diffuse poetic sophistication onto more readily accessible and less controversial iconic objects.

Despite Nabokov’s assertion that in Lolita he "revived" the modern term nymphet directly from its Greek predecessor, recent, literary scholarship has proven his claim to be suspect. From where did Nabokov retrieve the description of the nymphet and was he the first modern writer to transform the etymology of the word into its contemporary meaning?

Apparently Nabokov believed he had coined and therefore owned the term "nymphet" — as well as its various translations — when in 1960 he declared his intention to sue a French company that was about to make a film entitled Les Nymphettes. It is quite tricky to determine what measure of bad faith may have entered in a claim that was made at the very time when Nabokov was writing his screenplay for Kubrick. As critic Maurice Couturier has indicated, our author had indeed overtly acknowledged French 16th-century poet Ronsard's antecedence, during an interview he'd given for the French magazine L'Express barely six months earlier. However, he did state that the meaning underlying Ronsard's nymphet — a frolicsome little nymph addressed in a rather carefree and salacious song in the vein of the Roman elegists — was quite different from that with which Lolita is endowed. It is also true that Nabokov, a devoted taxonomist in the field of Lepidoptera, was responsible for devising a series of parameters and criteria which have come to define the contours of the nymphet, thus turning her into a type, in the zoological sense. Before him, 16th and 17th-century French and British poets had made use of the term “nymphet” as a diminutive within a mythological context, but without affording this creature any recognizable, individuating traits. Later on, in 1915, British writer John Louis J. Carter did publish a short novel called Nymphet, featuring a 12-year old girl involved in a love triangle with a mature man, but this work didn't leave any lasting trace in our culture. So, to answer your question: it depends, of course, what you mean by “modern” — the French consider that “modern” times start with the end of the Middle Ages and end with the French Revolution — but I'd say that Nabokov revived and refashioned a word which had been occasionally used as a poetic conceit during the Renaissance but which had fallen in oblivion since.

In addition to Lolita, the characters of the pedophile/nymphet appear in "A Nursery Tale" (1926), Laughter in the Dark (1932), The Gift (1935), and The Enchanter (1939). Nabokov was also an avowed fan of Lewis Carroll and was responsible for the first Russian translation of Alice in Wonderland in 1923. What all this means is that the character of Lolita has to be seen not as a momentary example of Nabokov’s interest in ephebophilia, but rather part of his integral fascination with the young girl in representations of women. You write rather beautifully on this subject that Nabokov’s motto was "caress the details," all the more so when these details belong to a woman. The "father of Lolita has indeed a weakness for female portraits, which he limns with utmost care, lingering on the woman’s colours and contours with chiaroscuro’s gentlest touches […] [I]n his attempt to frame women, Nabokov rises to the challenge of outstretching the frame of literature." To what degree do you think we can separate Nabokov’s descriptions of the young girl between some kind of rhetorical or poetic conceit, as opposed to an over-sexualized, fantasy/fetish figure?

In an essay entitled “Inspiration,” Nabokov identifies inspiration as a “nubile muse.” In the case of this writer, then, the poetic fuses with the sexual in the figure of the young girl, and more specifically the nymphet, a creature all the more attractive since it represents “the great rosegray never-to-be-had” (Lolita) and affords his male protagonists and narrators a transient glimpse of the ineffable, the absolute of art. As you have noted, Nabokov’s fictional world is peopled with such myriad figures of desire: to your bibliographical list, I wish to add Bend Sinister (Mariette), Invitation to a Beheading (Emmie), the poem “Lilith,” Ada (Ada and Lucette), Look at the Harlequins (Bel) and his final unfinished novel, The Original of Laura (Flora). These nymphets could be considered as Nabokov’s peculiar figuration of the age-old pantheon of muses, with its strong — yet not, in my view over- — sexualization of the creative impulse that springs from their appeal. And as I have shown in my PhD dissertation, it is often when depicting the nymphet's body that Nabokov's words become most radiant. Take for instance this passage from The Enchanter — the Lolitan Urtext, written in Paris in 1939 — where the main character observes the little girl during her sleep: “He dared not kiss those angular nipples [...]. His eyes returned from everywhere else to converge on the same suedelike fissure, which somehow seemed to come alive under his prismatic stare.” Notice how the writer arrests the reader's gaze by choosing an unusual term, “fissure” and an almost oxymoronic combination, “suedelike fissure,” yoking together textile and mineral realms, to designate the female genitals. With the term “fissure,” the pedophile's fascinated gaze not only seems to petrify the girl's body into that of a china doll, but also suggests its solution of continuity is not natural, making it vulnerable — as if this breach invited penetration, or else had let something from inside flow outside. Interestingly enough, Nabokov had also used this term — or rather, its Russian equivalent — to refer to his future wife's eyes after their first encounter, when he was aged 24:

Into the night, returned the double fissure

of your eyes, eyes not yet illumed

Although the erotic is less foregrounded, once again, the female body is characterized by some kind of insistently gaping lack or mystery awaiting to be filled or plumbed by the desiring spectator. These are excellent illustrations of Roland Barthes’s famous statement from The Pleasure of the Text (1973): “The most erotic portion of a body [is] where the garment gapes [...]; the intermittence of skin flashing between two articles of clothing [...], between two edges [...]; it is this flash itself which seduces, or rather: the staging of an appearance-as-disappearance.” An “enchanter” himself, Nabokov time and again glides back, through his prismatic and caressingly legerdemain art — and hence with complete impunity — to the intermittency of that gaping fissure, which thus becomes a topos, a common place, but one which he is able to toy with and remodel, sometimes self-mockingly, as in Ada when Lucette, referring to a film in which her own sister Ada acts the part of Dolores: “‘I’m like Dolores — when she says she’s ‘only a picture painted on air,’’’ — to which Van answers: “‘Never could finish that novel — much too pretentious.’”

¤

LARB Contributor

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Portrait of the Young Girl: On the 60th Anniversary of Nabokov’s Lolita Part IV—An Interview Series

An interview series dedicated to the imagery of Lolita and the young girl

A Portrait of the Young Girl: On the 60th Anniversary of Nabokov’s Lolita Part III — An Interview Series

An interview series dedicated to the imagery of Lolita and the young girl.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!