THE FIRST TIME I saw Taylor Negron was at Beth Lapides’s UnCabaret, back when it was at LunaPark on Robertson. It was probably some time in the mid-’90s. He told a story about going to the beach as a kid, and driving home with his swim trunks full of sand, eating a basket of warm raspberries in the back seat of the family car. It was a simple story, a story about a moment, but his description of the sweet berries exploding in his mouth, the juices running down his chin, was so open-hearted and sensuous, I found myself utterly transfixed by it. He was like nobody else I’d ever seen on stage: gorgeous in a high-cheek-boned way that was masculine, feminine, and leonine. He was both innocent and completely knowing. He was dignified and dirty. He made us laugh, hard, as he simultaneously linked us to the divine and universal experience of sweet, delicious berries.

In the endless march of comedians of the 1990s, with their relentless repetition of setup, punch, and callback, Taylor Negron was unique — a rose among the brambles. He was more than a stand-up; he was a humorist in the great oral tradition of Hans Christian Andersen or Will Rogers — a Scheherazade in shirtsleeves. Taylor was a born entertainer, and had a way of telling a story that riveted you to your seat no matter what the subject — though the subject was usually himself. His language was at once lyrical and conversational, his powers of observation sharp; he saw the details that others left out, and the obvious pleasure he took in relating them was delicious. His stories unspooled easily, casually, but any pro could see beneath the surface the impeccable timing and the hours of rewriting and rehearsal that went into them. What I loved about listening to Taylor was the way he licked his words as he spoke them. He enjoyed the sound of his own voice, which is essential to any good performer. He had an ear for rhythm and cadence and a way of joyfully lilting his “L’s” as he moved, fluidly, languorously, between the elegant and the lewd.

The next time I saw Taylor was probably two years later, at Mordigan’s nursery, back when Mordigan’s was at the eastern end of the Farmer’s Market, before it got plowed under for the Grove. It was a slow weekday afternoon, and I was wandering among the native plants. He was the only other customer in the store, and, of course, I recognized him immediately. We made eye contact and smiled. His aura, if I may use a word Taylor might not approve of, was powerful. He was simply a radiant human being. I could feel warmth and vitality coming off of him in waves.

I made it my business to find out who this man was. I have to admit: I became a wee bit stalkerish about Taylor in the years that followed. I learned he was a fairly well-known actor I had never heard of, with a name that caused me no small amount of cognitive dissonance: “Taylor” belonged to four girls in my daughter’s third-grade class. As the years went by, as I raised my children and began writing and performing my own stories, I thought of him often. I relished the idea that someday we would be friends.

I went to his shows, was introduced to his friends, and vanquished whatever degrees of separation stood between us. It wasn’t hard to do as Taylor had as many friends as a sane man could manage, and we shared colleagues in the burgeoning Los Angeles writing/performing/acting/storytelling community that Taylor helped pioneer and nurture.

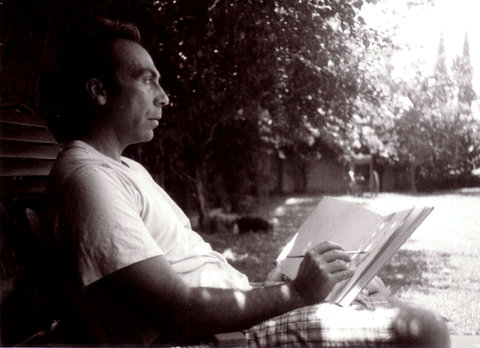

Taylor in Palm Springs, 2001, Polaroid by Mark Schwartz

Taylor in Palm Springs, 2001, Polaroid by Mark Schwartz

Taylor was, in his own words, “fame-ish” rather than famous. He referred to himself in a recent piece as “that guy.” That guy you recognized, you knew you knew, but didn’t quite know how. His IMDb entry reveals a long career as an actor, mostly in vehicles that I missed. When I watched TV with my kids I might see him flash by in episodes of Zoey 101 or That’s So Raven. I remembered him delivering pizza to Jeff Spicoli in Fast Times at Ridgemont High, but only after the fact was pointed out to me. I watched his legendary “area rug” bit from Punchline for the first time a few hours after he died because people were saying “area rug” in my feed and someone sent me the link. It is 52 seconds of hilarious, classic, flawless Taylor. I was the last to know about it.

Taylor’s fame-ish-ness was part of his pixie dust, and it spiced much of his conversation. If he referred to his friend “Lucy,” you could be pretty sure he meant none other than Lucille Ball. He dined out on celebrity, but it wasn’t what gave him sustenance. That came from making art and friends. If he had fans, it wasn’t because he was a huge star, but like a star, he had gravitational pull. Taylor could have been stuck in a cubicle in Van Nuys doing data entry, and everyone would have wanted to be near him, he was that charismatic.

But Taylor was always meant for fabulous things. He was a local boy who grew up, in his own words, “California Gothic.” His childhood house was in Echo Park, on grounds where the old Mack Sennett studio once stood, and there he watched black-and-white movies with his film-besotted grandmother. He came of age in Glendale during the Charlie Manson era, and he remembers seeing Joan Didion crying at the steering wheel of her green Jaguar “on Moorpark, below Ventura.” He used to say, “I remember when the palm trees were short and Tomorrowland was modern.” Taylor was made of Los Angeles — woven from palm fronds and eucalyptus, red carpet and call sheets. He connected old Hollywood to new Hollywood. He knew Mae West and the Olsen twins. He knew everyone, worked with everyone, and was loved by all.

Taylor was to the camera born. He could orient toward key light like a lizard tracking the sun. This might have made him insufferable had he not such a love for and ability to recognize talent and beauty in others. Talent thrilled him, and he was always ready to swing the klieg light onto the person standing next to him. Hell, he was the klieg light. To be loved and beheld by Taylor was to find yourself warmed and well lit.

Taylor performing in New York, May 2013

Taylor performing in New York, May 2013

After almost two decades of flirtation, Taylor and I finally had our first official date in June of 2012. He invited me over to his shabby-chic Silver Lake apartment for dinner. Of course, the boy who loved berries grew up to be an exquisite cook. He was very European in the kitchen, chopping herbs on a worn chopping block, tossing everything into a well-seasoned Le Creuset pot, free-styling the recipe as we gabbed non-stop. Taylor was a brilliant conversationalist, simultaneously ribald and refined, a vivid raconteur, able to surf any subject, digressing into delicious anecdotes that he buttoned up with perfect punch lines. He was also a good listener and a canny reader of people. That night, when I told him I had gone to boarding school as a kid, he laughed and said, “Oh, I know you. You were raised to be unique and iconoclastic, but secretly you yearn to be a part of the group.” Bam. Taylor.

As we talked I kept dog-earring other topics I wanted to parse with him. There wasn’t enough time for us to get to all of it, but we did our best, staying up until 2 a.m. As I drove home, both sated and stirred up, I felt once again that I had touched the divine. I wanted more of him and yet I knew that the price of loving someone so magnetic was that I would never ever get enough. And I never did.

Taylor Negron passed away on Saturday, January 10, after a seven-year battle with cancer, the details of which he kept private from all except his closest circle, most of whom were with him in his final few days. He leaves behind friends, fans, and family — all bereft and struggling to make sense of a future suddenly made dimmer by his departure.

I didn’t know Taylor Negron the longest, or the best, but like all who loved him, I am grateful for the moments I shared with him, a man who had, above all, an exquisite sense of moment. If there’s a heaven, Taylor Negron is surely there now, telling stories about all of this, eating warm berries, sticky with the sweetness that was his beautiful and all-too-short life.

¤

LARB Contributor

LARB Staff Recommendations

America Hates Women

Bad Feminist brings an inclusive and modulated voice to what has been, at times, a shrill conversation.

Fifty Years of Rechy's "City of Night"

On the 50th anniversary of his first novel "City of Night," John Rechy talks to Charles Casillo about its publication and its impact.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2015%2F01%2Ftaylor_negron.jpg)