Lucian Freud, sleeping by the lion carpet, 1996, oil on canvas

(1922–2011) / private collection

photo credit: © the Lucian Freud Archive / the Bridgeman Art Library

“Thinking in pictures is…only a very incomplete form of becoming conscious. In some way, too, it stands nearer to unconscious processes than does thinking in words, and it is unquestionably older than the latter both ontogenetically and phylogenetically.”

— Sigmund Freud

LUCIAN FREUD liked to say that he admired his grandfather most as a zoologist. “Lucian’s passion, absolute passion, for animals, even dead animals,” observed the Picasso biographer John Richardson, “like having a stuffed zebra head and dead chickens and things, all that came straight from Sigmund.” Animals were always part of the painter’s repertoire of portrait subjects. Dogs, horses, rats, monkeys, cats, birds — both on their own and in the company of humans — appear everywhere in his canvases. He always lived in the midst of a menagerie as well. He’d loved horses since childhood, rode them, and sometimes slept in the stable under the same blanket with them, resolving early on to be a jockey if he couldn’t be a painter. Dogs were constant companions, and, especially as he grew older, his own face came increasingly to resemble the elongated countenance, at once pointed and willowy, of his whippet, Pluto. He cuddled foxes on occasion. Within the walls of his different homes and studio spaces there were, at times, sparrowhawks, kestrels, and other birds of prey. His own hard stare was compared to that of a winged predator.

After Lucian Freud took over his grandfather’s home in Hampstead, Stephen Spender rented the attic apartment of four rooms, the largest of which he let Lucian use as his studio, a space the painter filled with dead birds. Geordie Greig, in his shamelessly distracted, potpourri biography, Breakfast with Lucian: The Astounding Life and Outrageous Times of Britain’s Great Modern Painter, recounts the surreal backstory to a famous photograph depicting Lucian Freud in bed, looking like winter, primevally ancient, while Kate Moss curls around him from the side — high summer personified, sated and golden. A director making a movie about Lucian in his 86th year had brought a wild zebra into her film studio for the painter to ride, as a playful allusion to the recurrent depictions of these animals in his paintings. When Lucian tapped the zebra on the nose and the zebra broke loose, the painter gripped the reins and wouldn’t let go. The zebra threw him to the floor, then pulled him across the studio. David Dawson, Lucian’s longtime assistant, thought it would be the end of him. He was hurried to the emergency room. The shot of Moss entwined about Freud was taken while he was recuperating in the hospital from being dragged along a studio floor by the zebra.

Freud was drawn to something feral in Moss’s own nature as well, which is why in her case he made an exception to his rule of not working with professional models. The restaurateur Jeremy King recounted that Freud spoke of Moss exactly as he talked about foxes. “He liked the free spirit. He liked the bite of danger,” King asserted.

But while Freud’s interest in the frisson of danger was real, his fascination with animals, both wild and domesticated, went deeper, calling to mind his grandfather’s explanation, in a letter to Marie Bonaparte, for his own attraction to the canine tribe: “Dogs love their friends and bite their enemies, quite unlike people, who are incapable of pure love and always have to mix love and hate in their object relations.” The idea of pure feeling obsessed both men. For Sigmund, the impossibility of actualizing pure emotion lay at the root of human suffering. In Lucian’s case, the embodiment of such feeling remained a real aspiration.

The profound connection between these two observers of humanity was hinted at by a snarky online comment posted in the Daily Mail about one of Lucian’s best-known paintings, a nude portrait of an immense woman nestled on a threadbare couch. “Benefits Supervisor Sleeping, is the reason why clothes are the world’s greatest invention,” went the wisecrack. In the sense that clothing helps us to obscure our true nature, Lucian might have agreed. Discussing the challenge of painting nudes with Michael Auping in an interview reproduced for the finely executed catalogue of Lucian Freud: Portraits, an exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in London and the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Lucian noted, “There is, in effect, nothing to be hidden. You are stripped of your costume.”

The painter’s distaste for disguise extended to cosmetics. After speaking with one heavily made-up woman, he protested, “I felt I couldn’t see who I was talking to.” This bias resonates with Lucian’s confession that “I am inclined to think of ‘humans’ […] if they’re dressed, as animals dressed up.” More indicative was his claim to be only “really interested in people as animals […] I like people to look as natural and as physically at ease as animals, as Pluto, my whippet.”

In another portrait of Sue Tilley, the enormous woman of Benefits Supervisor Sleeping (which set a record price, at $33.6 million, for a painting by a living artist), Freud made such associations explicit. For the vertical composition, Sleeping by the Lion Carpet, Tilley is depicted slumbering in a brown armchair, her head fallen to one side, her left arm draped over a colossal thigh, her right hand twisted up and back to prop her face, cheek squished into her palm. A large figural carpet, elevated off the floor so that it covers the studio wall behind her, shows a pair of lions stalking a group of gazelles. Tilley’s form seems to belong to this fantastical wild habitat, with its lush indigo sky and tawny hides, in some far more substantial fashion than to the dull gray-brown floor at her bare feet. Indeed, her head is positioned in such a way that it might almost be painted into the carpet, just beneath the lower lion, which is crouched, preparing to spring. She might also be construed as dreaming the primeval background scene that frames her face, her closed eyes screening the final moment before the hunt becomes a kill.

¤

Often Freud’s models would end up sitting for him for over a hundred hours in a process that could last many months, sometimes years. Embarrassment about the way one looks falls away under the glare of so prolonged a stare. Not all the emotions that replace it need be desirable, but that particular, red-faced register of being on display must begin to dissolve before Freud could paint. He believed that, in the end, the sitter’s pose evolved to reflect his or her own foundational identity.

In Man with a Blue Scarf, the critic Martin Gayford’s quietly enlightening account of sitting for two portraits by Lucian Freud over the period of a year and a half, Freud’s commitment to shamelessness, both in his own life and in the self-manifestation of his sitters, crops up repeatedly. Freud plainly relished unsettling others with anecdotes of his days in Paddington in the 1950s when a number of his friends, neighbors, and subjects were criminals. He expressed mild contempt for those of his pals, like Stephen Spender, who prized the standard virtues and wanted to be liked. “Better than wanting to be disliked, perhaps,” Gayford countered. “My idea was always to be feared,” Freud responded. His underworld companions robbed banks, slashed their enemies’ faces with razors stuck in potatoes, and doped dogs at racetracks. “I thought that was really clever and imaginative,” Freud noted of the last crime. At one point Freud remarked to Gayford of a mutual painter friend, “He has a quality that only the very best people and the very worst have, he’s absolutely shameless.”

Clearly, Freud enjoyed the tingle of shocking expectations, but he also knew just how far he could go before real alienation kicked in. You don’t end up leaving a £96 million will as Freud did — the largest sum ever bequeathed by a British artist — having lived in radical defiance of all social rules. Greig registers Freud’s deft navigation of English society but leaves it unanalyzed. A materialist study of Freud’s career has yet to be written but could prove more revealing than all the googly-eyed reiterations of his famed “Lothario” propensities.

In any event, freedom from shame was something that sitting for Freud could, at least temporarily, impart to sitters as a kind of therapeutic side effect. Tilley reported how her initial nervousness about stripping before Freud was short-lived. She soon grew used to being naked before the artist, and this familiarity was complemented by a sense of falling in love with the painting Freud was creating of her. “I’m not the ‘ideal woman,’ I know I’m not,” Tilley later said. “But who is? And he never made the skinny ones look any better. He picks out every single detail.”

The fantasy vision of the painter’s studio as a place where every sitter is seen fully, through and through, constitutes a radically egalitarian realm. The person who can see all our flaws — every last quirk of our fleshly being — would come to understand these defects so completely, and place them in so wide a context, that they would cease to be stigmata. Refusing the fetishistic focus on a single grotesque trait, the perception of ugliness would come full circle to where awareness of beauty is regained. In this way, Freud’s studio had the quality of a dream tribunal at which the defendant accused of dreadful things is given space to lay out with unlimited expansiveness the ways that he or she is not the monster depicted by the prosecution, but so much more besides and something else entirely. Freud enjoined his sitters to do nothing but be, in his words, “punctual, patient and nocturnal,” while holding nothing back in the visual confession they made before him of their physical being.

The illuminating effect of shedding shame and self-consciousness could work both ways for painter and model. Speaking of Benefits Supervisor Sleeping, Freud told an interviewer that he’d initially been “very aware of all kinds of spectacular things to do with her size, like amazing craters and things one’s never seen before.” But over time, as Sarah Howgate notes in a perceptive essay for the Portraits exhibition catalogue, Tilley “became more ordinary to him.” In place of the spectacular, he came to recognize the intense persistence of Tilley’s essential femininity. Freud acknowledged being drawn to extravagant bodies and, as much as he mistrusted this predilection in himself, continued to seek them out as a kind of testing ground for his powers of concentration, striving to see through the temptation of physically sensational features to the ur-forms preserved beneath their monumental rolls.

“You must make judgments about the painting, but not about the subject,” Freud once stated. Such an attitude requires striving to see past any single feature of the sitter in isolation, even if that trait is ravishing. In his book, Greig asks the painter, “And with the portraits of Caroline [Blackwood], were her enormous luminous eyes what was important?” “I never really think of features by themselves,” Freud rejoins. “It is about the presence.” The answer correlates with what Gayford calls Freud’s lack of sympathy for references to people having, for example, appealing eyes, legs, or busts. “I would have thought that if you wanted to be with someone, you would find everything about them erotic,” Freud remarked to Gayford. For the period of the sitting, anyway, Freud wanted to be with all his subjects, and this communicated powerfully to them. One model observed that posing for him “felt like being an apple in the Garden of Eden. When it was over, I felt as if I had been cast out of Paradise.”

But what, then, ends up on display for the viewer? What happens when the depth of dialogue between painter and sitter has enabled the artist to break through easy, socially conditioned responses to the human physique in order to portray some more fundamental quality than the labels “beautiful” and “ugly” typically suggest? These questions point to others about the nature of Freud’s art. He’s regularly characterized as a masterful realist painter, but that label may obscure more than it elucidates. If we’re studied as relentlessly as Freud purportedly observed his subjects, is the image on the canvas necessarily more objective? Or does the hypertrophied focus and temporal extension of the gaze mean that the rendering of the subject must then reflect the seer’s own psychological landscape? “My work is purely autobiographical,” Freud once announced. “It is about myself and my surroundings. It is an attempt at a record. I work from the people that interest me and that I care about, in rooms that I live in and know. I use the people to invent my pictures with, and I can work more freely when they are there.”

And what about all those moments in Freud’s work where elements of the surreal blatantly intrude into the realist frame, as in the painting that shows a naked man nursing a swaddled infant, while in the foreground an older man calmly reads a book with a gray dog curled at his feet? Or the early interior, The Painter’s Room, in which an enormous red and yellow zebra head juts through a square-cut window in a blue wall to hover above a tattered couch, evocative of the psychoanalytic patient’s lying-place? Or the portrait of a naked man in a weak contrapposto pose on a draped bed embracing a whippet, while another set of legs identical to those of the subject emerges from under the bedcovers along the floorboards?

The realist label for Freud’s work seems to correspond with his professed intention to make paint “work as flesh.” The thick, textured, dimensionality of his mottled oils is epidermal, to be sure. But something mystical creeps in when Freud appends to this aspiration the wish that his portraits “be of the people, not like them. Not having a look of the sitter, being them.” The label becomes more suspect still when we probe the question of what the reality of flesh consists in. While Freud talks of his intention to depict just what he sees, he elsewhere says, “The artist who tries to serve nature is only an executive artist.” To Gayford he expressed distaste for Picasso’s wish to make paintings that “amaze, surprise and astonish.” In remarks for the catalogue of an exhibition he curated of favorite paintings by other artists he asserted, “What do I ask of a painting? I ask it to astonish, disturb, seduce, convince.” Often Freud talked of despising paintings that exhibit theatrical propensities. Yet, in conversation with Auping, he mused that his painting was “a kind of unconscious theater. In an ancient world, painting and theater would probably be considered very close,” Freud opined.

Whatever else, his paradoxical comments reinforce the impression of artistic ambitions aimed backward toward the borders of myth, bent on evoking those primordial figures and configurations that spawned humanity’s mythic vision. It’s true, as well, that both Freud and his sitters commented on the “prophetic” character of his portraits — specifically the way he seemed, on occasion, to inscribe the imminence of death, self- or time-inflicted, on the lineaments of his models’ features. The writer and heiress Caroline Blackwood, who was once Freud’s lover and model, noted grimly that the eyes of his sitters as they gaze out from his portraits “suggest that, like the blind Tiresias, they have ‘foresuffered all.’”

¤

Another sensation tendered by the experience of sitting for Freud was release from consciousness of time. In part this was due to the sheer magnitude of the temporal commitment to which each model agreed. How could sitters have continued to tick off minutes when they knew the sessions might ultimately consume 150 hours or more of their existence? That trademark woe of our age — pointless freneticism, the ricochet between communication devices and the attendant pressures of our go-go reactive, ding-dong automaton lifestyles — had to be let go in Freud’s studio. His attitude, as he conveyed it to Gayford, was the reverse of working to a deadline. “When one is doing something to do with quality, even a lifetime doesn’t seem enough,” Freud maintained.

By virtue of his eccentric personality, Freud seemed able to create an atmosphere that displaced sitters as well from the customary axes of their lives. Gayford described his hours modeling for Freud as “remorselessly intimate,” in a manner that bore affinities to marriage, crowding out other friendships and responsibilities. “It is an experience almost like returning to youth, endless time and nothing to do, for the sitter at least, except chat,” Gayford wrote. “I’m not sure whether it is filling a hole in my life, but it is enthralling.” Elsewhere he likens the experience of posing for Freud to meditation, a comparison that resonates with his daughter Bella’s observation that the attendant break from daily routine “makes you conscious of life going on in the nicest way possible."

Needless to say, the economic reality of interrupting mundane life required, at the least, a flexible work schedule. Though Freud often paid his sitters something — on occasion with an etching of the oil portrait he was painting of them — many of his models were well able to afford their time off from rote being. Mostly, he compensated subjects with his own dashingly entertaining conversation and by cooking them fancy game or lobster dinners accompanied by champagne — repasts that factored as part of the painting process.

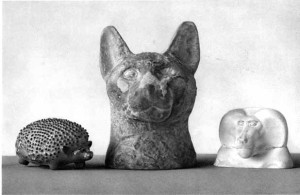

Animal mummies, cats: roman period, 1st century ad, London, British Museum from History of Egypt by J.H. Breasted

Animal mummies, cats: roman period, 1st century ad, London, British Museum from History of Egypt by J.H. Breasted

Gayford observes that journalism — his own profession — does not require sustained effort, but “can be done on a rush of adrenaline, then on to the next thing. Maybe that’s what’s the matter with it,” he muses. “Watching LF paint my portrait is making me think about the way I work myself. It is an example, enacted before my eyes at every sitting, of measured, steady progress towards a final goal.” This steadiness in no way precludes discursion; rather, such attention, again like meditation, enlarges his field of vision, allowing him to understand the context for his undertaking. Lucian also had a kind of spiritual reverence for the relationship between his subjects and their larger setting. “I like the models to be around in the studio even when I am painting something else,” he once said. “They seem to change the atmosphere, in the same way that saints do, by their presence."

The particular sense in Lucian’s subjects of having been granted dispensation to detach and unwind from the contours of habitual behavior evokes, as well, the world of Sigmund Freud’s consulting room. There, too, for months or years on end, analysands positioned in a state of repose allowed that which was hidden deep within to be slowly coaxed into visibility, or at least audibility. The precisely choreographed room where Sigmund saw patients — evocatively lit, mysteriously arrayed with antiquities, muted, secluded from the outside world — made for a chamber where patients’ fantasies and dreams felt at home, able to emerge and become subject to the doctor’s verbal dissection. Gayford describes Lucian Freud’s studio as a kind of operating theater, constructed in relationship to light so as to allow sitters to be viewed from multiple angles in the most controlled, revealing manner possible. Lucian’s demeanor while painting resembled that of “an explorer or hunter in some dark forest,” Gayford writes.

But what, finally, do these loose parallels between the practice of the doctor and the artist signify? To speak of a release from shame and time as therapeutic benefits is not to imply that these rewards were ever intended as such by the artist himself. No one — Lucian least of all — ever pretended that the experience of posing for him was meant to be in the service of anything but his painting. Why, then, was it in Lucian’s own interest for his subjects to enter into an unselfconscious meditative state analogous to that which Sigmund Freud sought to engender in patients? What, finally, is the relationship between the two men’s endeavors, and what can we learn from considering them in conjunction?

¤

An intriguing link between the two men can be traced through the work of James H. Breasted, an American Egyptologist. Breasted, who participated in the excavation of King Tutankhamun’s tomb and became one of the world’s foremost archeologists, was also a respected scholar of the ancient world. When the German-language version of his history of Egypt was published in the 1930s, in an edition rich with color plates and line illustrations, it became the standard work in Germany and Austria, where the discipline of archeology held exalted stature. Sigmund Freud considered Breasted’s work “authoritative” and drew on it in his own research into the evolution of human psychology.

Lucian Freud was presented with a copy of this same book when he turned 16 in 1939, and the volume remained a reference point, inspiration, and portrait subject in its own right throughout his life. He made two portraits and an etching of the book open beside a gray pillow, as well as a painting of his mother reading the work. No other book is so featured in the painter’s work.

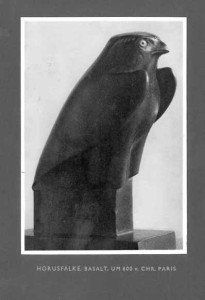

Horus Falcon, Basalt, c. 600 bce, Paris from History of Egypt by J.H. Breasted

Horus Falcon, Basalt, c. 600 bce, Paris from History of Egypt by J.H. Breasted

The frontispiece of Breasted’s Geschichte Aegyptens (History of Egypt) presents a color photo of a bird of prey figurine. Turning the pages, one encounters a striking panoply of human portraits, along with lions, cats, gazelles, baboons, and mythic hybrid creatures, like sphinxes. It’s easy to conceive how the artist, young and old, would find the book transfixing. But in the three portraits where the book’s open pages are legible, Freud always shows the same two-plate spread depicting a pair of plaster portrait heads from the workshop of the sculptor Thutmose at Amarna. Sarah Howgate has pointed out how these twin portraits resemble two small unfinished self-portraits by Lucian, which are propped side by side against a wall in the background of his painting Two Irishmen in WII. The flaking, granular quality of paint in Freud’s final work, Portrait of a Hound, a nude portrait of his assistant, Dawson, beside a whippet whose hindquarters are dissolving into blank space, is also eerily suggestive of the texture of plaster in the Egyptian heads. Speculating on why the pair of ancient portraits were so important to Lucian, Gayford notes that the Egyptians in this era created the “earliest great portraits” still extant. They are “wonderful representations of specific individuals,” he adds, and perhaps as such were understood by Lucian as “representations of pure being."

Along with the history of Egypt, a second work by Breasted also proved seminal to Sigmund Freud’s thinking. Breasted’s The Dawn of Conscience was, in fact, the single greatest influence on Freud’s last major essay, the controversial Moses and Monotheism. Breasted’s book makes the argument that conscience — and, arguably, human consciousness as such — originated, not as Biblical sources contend among the Hebrews, but within Egyptian society during the brief, revolutionary reign of Amenhotep. Amenhotep, Freud wrote (following Breasted), developed a religion with marked similarities to early Judaism, most notably in its swerve from a universal god or gods to exclusivist monotheism. Sigmund dates the start of Amenhotep’s rule to about 1375 BCE and quotes Breasted’s reference to this pharaoh as “the first individual in human history.” Moses and Monotheism, published in 1937, used Breasted’s arguments about Amenhotep’s character to make the case that Moses was by blood an Egyptian who’d been heavily influenced by that ruler and left Egypt after Amenhotep’s death to found his own religion.

Small sculptures, late 18th dynasty, Berlin. from History of Egypt by J.H. Breasted

Small sculptures, late 18th dynasty, Berlin. from History of Egypt by J.H. Breasted

Freud’s motivations for writing this work, which was castigated for depriving the Jews of their heroic lawgiver right at the outbreak of World War II, were complex. But critics of Freud’s book tend to overlook the extreme ambivalence of the doctor’s portrait of Amenhotep. On the one hand, per Breasted, Freud designated him as history’s first individual. However, Amenhotep was also responsible, Freud argued, for bringing Egyptian religion “greater clarity, consistency, harshness, and intolerance.” Freud himself was never a monotheist, and in 1939 the decision to create a revisionist genealogy of the charismatic founder of a harsh, intolerant faith was hardly a simple paean to moral genius. Freud’s interest in tracing Moses’s roots reflected his concern with trying to excavate the psychological situation that gave birth to human conscience — a moment which also might be said to mark the appearance of the first “symptom” from which all subsequent human neuroses evolved. While conscience was essential for the survival of civilization, it also represented for Freud the disease that no one “civilized” could ever truly recover from.

It’s not coincidental that the double-page spread in the Egyptian book which Lucian received the same year his grandfather published Moses and Monotheism — the two portraits that he paints again and again — are dated to precisely the period that struck his grandfather as foundational for the human predicament. The head on the left is dated to around 1400 BCE, the head on the right to 1370 BCE. According to his grandfather’s dating scheme, they thus perfectly span the period just before and after Amenhotep’s assumption of power, tracking between them the dawn of human conscience and individual consciousness. Lucian Freud was obsessed with “the individuality of absolutely everything,” Gayford reports, not just people and animals, but eggs and other objects as well. At the same time, he had a phobia about being photographed and a devout hatred of activities he perceived as efforts either to conceal or counterfeit people’s biological identity.

Titan, Diana and Callisto, 1556–1559, oil on canvas, 74” x 18.5”

Lucian described himself, indeed, on more than one occasion as a biologist, explaining that he liked to paint nudes because of the way the naked body served as a translucent window onto forms that lay deeper underneath. “One of the most exciting things is seeing through the skin, to the blood and veins and markings,” he remarked to the art critic William Feaver. Above all, Lucian used his vision, his understanding of selfhood as something distinct from the usual confluence of ego and identity, to make the case for a kind of animal individuality. As Marina Warner once noted, Lucian was a determinist who “paradoxically managed to restore to the naked body its character as the inalienable possession of an individual.”

Yet if both Sigmund and Lucian felt driven to look backward to a moment when the human countenance could still express “pure,” biologically defined being, their rationale for doing so was ostensibly antithetical. Whereas Sigmund’s psychoanalytic project was, in theory, dedicated to helping people become more conscious as a way of helping them acquire a measure of perspective and control over their drives, Lucian was interested in returning his subjects — or at least their bodies — to the depths of unconsciousness. While his grandfather studded his consulting room with ancient figurines from Egypt, Greece, and Rome as totemic spirits that might catalyze the analytic process of exorcism, tempting the patient’s incubi to emerge by way of sympathetic identification, we might say that Lucian Freud sought to transform his subjects back into those ancient dream-beings from which modern human psychology evolved.

Once again, what all this means for viewers of Lucian’s canvases is, of course, debatable. What would appear in a portrait that actually succeeded in depicting pure being? In Lucian Freud’s idiom, might this ideal represent the point at which our most archaic selves and absolute individuality converge? If the painter’s true aspirations, in life and art both, were aimed at getting beyond the symptom of conscience, what are we left with but raw id? Caroline Blackwood, who knew well what it felt like to be painted by Lucian, to be both intimate with him and sexually betrayed by him, to drive him out of his mind and into a state of pure anguish when she’d left him, once wrote, “Lucian Freud has always had the ability to make the people and objects that come under his scrutiny seem more themselves, and more like themselves, than they have ever been — or likely will be.” In this richly enigmatic observation we glimpse the start of an answer to many questions raised here.

Blackwood implies that a painting might so far transgress the boundaries of mere semblance as to literally reconstitute an aspect of the subject’s reality that the subject herself has surrendered to social constructs. In so doing, she hints at a third form of delivery conjured in Freud’s studio. But to chart this last release we must first consider a pair of Titian paintings that Lucian called the most beautiful pictures in the world.

Both paintings, Diana and Actaeon and Diana and Callisto (1556-1559), portray mythological scenes involving a fatal exposure of flesh. Each canvas shows a human subject unwittingly contracting sexual guilt in the eyes of the virgin-huntress goddess, Diana. In Diana and Actaeon, Actaeon is represented accidentally stumbling into the scene of Diana bathing naked with her handmaidens; Diana’s gaze is furious as she tries to veil herself from Actaeon’s helpless stare. In Diana and Callisto, Diana commands her own nymphs to expose the nakedness of her handmaiden Callisto, thereby baring proof of her illicit pregnancy (caused, in fact, by rape). Sexuality as such has doomed these human beings. Titian shows the figures in the instant before Diana moves to punish them.

“These Titians [...] have what every good picture has to have, which is a little bit of poison,” Lucian remarked. “In the case of a painting the poison cannot be isolated and diagnosed as it could be in food. Instead, it might take the form of an attitude. A sense of mortality could be the poison in a picture, as it is in these.”

Green slate tablet first dynasty, circa 3400 bce Oxford, Ashmolean Museum from History of Egypt by J.H. Breasted.

Green slate tablet first dynasty, circa 3400 bce Oxford, Ashmolean Museum from History of Egypt by J.H. Breasted.

But the sense of death pervading these canvases is only part of what gives them their aura of luminous, perilous imminence. Those who know their myths as Freud did will recall that, before being torn apart, Actaeon is transformed into a stag. Callisto, before dying, is turned into a bear, then set amid the stars. Both figures, driven to violate the rule of a god by virtue of an erotic nature for which they bear no responsibility, are changed into beasts.

Finally, we might conjecture that what Lucian Freud sought to portray in his profoundly disturbing, riveting canvases, was a form of emancipation from the human condition as such — the release of metamorphosis. The dream life of flesh is all made up of animals, the painter suggests. His grandfather, meditating on the collapse of European civilization in the late 1930s while reading Breasted’s history of Egypt, would have agreed. Ultimately, more even than trying to imbue the individual with knowledge that allowed control over the drives, Sigmund, like Lucian, sought to bare those animal truths that damn man’s efforts to deify himself, locating truth and beauty closer to the bone.

In the fall of 2013, Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum mounted the city’s first exhibition of Lucian Freud’s paintings. Throughout his lifetime, Freud persistently refused invitations from Viennese curators to display his work, refusing to exonerate the Austrian state from culpability in his family’s fate. Among the portraits on display in the posthumous show is a work depicting his lover Bernardine Coverley sinking into an old, dark, Freudian couch, face averted, breasts engorged, pregnant with the future in the form of their daughter, Bella. She’s pure physicality — but enlarged rather than reduced by that containment within the body. On the label is a note reading: “This painting is exhibited in memory of Sigmund Freud’s sisters, who were deported from Vienna and died in concentration camps: Rosa in Auschwitz, Mitzi in Theresienstadt, Dolfi and Paula in Treblinka.” The anonymous tribute in this haunted setting evokes a line Freud scrawled in charcoal over the densely paint-gobbed walls of his studio: “Art is escape from personality.”

¤

LARB Contributor

LARB Staff Recommendations

Photography’s Chattering Ghosts

Why do we trust, or distrust, photographs? What are the forces that exist behind these images and why do they command such authority?

The Secrets of Consciousness and the Problem of God

I. LET’S SAY YOU WERE GOD. How could you know this? How could you be sure that you weren’t rather a mad person, thinking you were God...

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2014%2F03%2FFreud1-resize-for-web.jpg)