In Lieu of Solutions by Violet Spurlock

To experience gender and transition, In Lieu of Solutions looks outside the self: seeing herself as love does, Spurlock finds love to be a reprieve from her own point of view. The opening poem, “Epidermal Ripple Pools,” charts the welcome contradiction of seeing her own changing body described to her:

We debate about my tiny titties.

— You think they are getting bigger,

— I think they are getting smaller.

° Predictable.

— You say that I don’t see myself

— From the side.

° See, that’s an argument.

— You may offer me sensory details

— About how you view my profile

— But I process it as evidence

° (Against my perspective)

— For which I am grateful

Talking about what one sees alters it, both for the speaker and addressee, and a recounted dialogue brings two structural aspects of the poem to the foreground: the image and the argument. Spurlock is relentless in her pursuit of denaturalizing the poetic image. She has no hope of distilling anything to its essence—what she says is what we get, which means that by the time we get to an image, it’s already been “processed” through filters of thought and communication. Words arrange their object, composing, and a poem can compose at 100x magnification. The reader has their own hand in image formation: “Are my titties an image?” she asks. “Perhaps for you.”

Looked on by a lover, such “eye-dent-titties,” à la poet and playwright Nazareth Hassan, become an interpersonal argument. Within the structure of seeing each other every day, neither of us really knows what the other looks like, let alone what I do: changes are too minute to track, but they add up to a conversation. And so bodies are subject to co-construction, and the word is a malleable building material: we put ourselves together, iteratively, in conversation.

If gender weren’t mostly for other people’s benefit, we wouldn’t put so much effort into it (I sweep my floors before friends come over, not once they’ve gone back home). A gender, like a text, is editable, taking place through collaboration in a simultaneous self-to-self and self-to-other relation. As Spurlock writes, “My brain is under my hair. A sort of river like an avenue. Speak with your eyes to the revised version.” Gender’s underneath and on top too. It is an opportunity to go somewhere, and it needs pedestrians and people sitting on their stoops to do its affiliative work.

Sitting around and talking are critical elements of Spurlock’s pro-loitering poetics. To steal an hour from the logic of jobs and reroute it through the logic of love is to produce a speculative material: what people could be if we had more time to talk to one another. Other people are also an intervention in the estrangement produced by a body in the process of change:

If (‘our’) body describes its own process of remaking I won’t write

Once normal hormone (simply by having no point of comparison)

Become completely alien (or is this merely the halfway feeling—

[‘our’] body’s hallway) the hot flash of tears touched down upon me

My breast buds unknotted in retreat always aching and weakness

The only strength is shared strength we feel it in crowds and beds

If hair is at street level, hormones are the body’s hallways: a departure that is still interior, a sentence that turns over rather than arriving at an end, leading … we’ll find out where. Wherever we’re going, there will be other people there, protesting and fucking, with any luck.

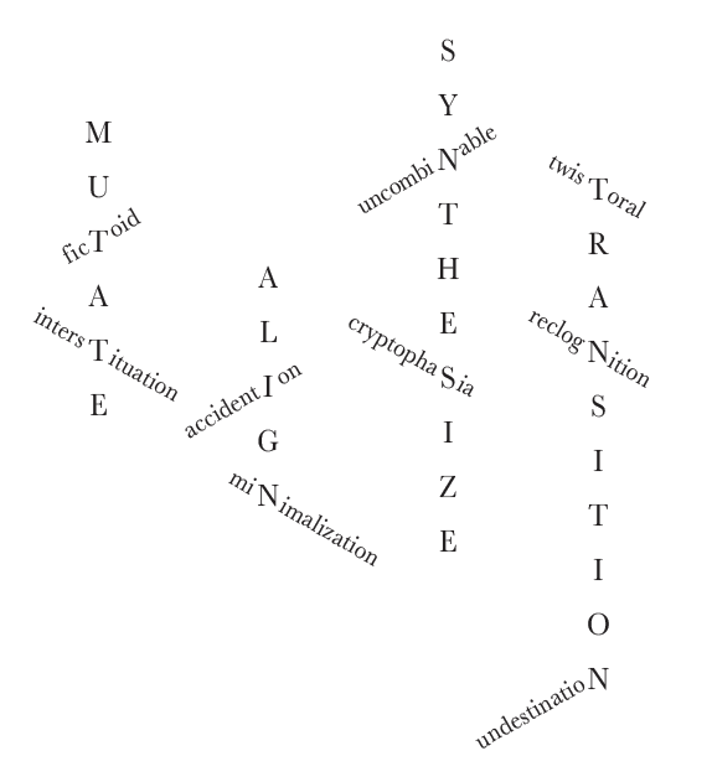

Across the book, poems reach out in form to find their directions, taking various shapes from tight columns to dense, wall-to-wall fields of boxed text. Toward the end of “Go By,” a series of visual poems branches off into word hallways, setting off from the starting point of a central word like “transition” to offshoots like “reclogNition,” an apt word for the gummy works of coming to see yourself while being seen by others.

Hormones are the condition under which one can encounter the obvious, the self. In Spurlock’s poems, our self-conceptions and their physical manifestations move in search of “undestination,” to meet the shifting words we use for them. Often, those words find their form in other people’s talk about their own bodies. “I will only feel right speaking of my own body but its totality is better represented by your parts so let me borrow them,” she requests, not quite politely. A conglomerate body is more honest than many formations of “we,” a unit which Spurlock takes an active interest in deconstructing. “[I]f you point out what / we ‘all’ have you probably / have quite a bit of it,” she points out early in the book. “We,” Spurlock proves, is never settled.

Still, totality, and finality, are temptations. As its title suggests, In Lieu of Solutions is an argument for the interminable process of avoiding a product. “Anyone interested in the solution is a problem,” Spurlock writes. This difficulty of continual remaking animates the book, showing the very concept of a social construct to be revisable for our own purposes, up to imagination’s limit: even stolen time from work takes the form of an “infinite lunch hour,” where work still frames what’s outside of it. These are the times when Spurlock invites us to stop making “sense and rent.” To do that, we’ll need each other.

The sociality of In Lieu of Solutions is environmental, coming to us from a context of Bay Area living room and backyard readings. Like many of us, I met Spurlock at a reading. Her poems live with friends as they engage in experiments to unfold the self within structures of sex and thought, activities better undertaken with company. Her partner, poet Sophia Dahlin, is an affectionate interlocutor throughout the book (in the title poem, Spurlock writes of her, “you see love in the world / by giving love to the world”). Reading In Lieu, I think of her bicoastal friendships with writers like Noah Ross, Bahaar Ahsan, and Lindsay Choi, as well as Shiv Kotecha and Rainer Diana Hamilton, whose own books are evidence that friendship and poems make each other possible.

In conversation with Hamilton for BOMB, Spurlock elaborates her intentions for a reciprocal poetics: “It’s also important to me to envision love between the book itself and the reader. The book should provide a container for the reader when they come apart, while also asking the reader to contain its own unraveling.” Spurlock shares this sensibility of falling apart and into each other with Bernadette Mayer’s “Walking Like a Robin,” which takes an instructional look at the aging, fragmenting body and its opportunities:

oh look, there’s some caviar

it must be my birthday, thanks

i must be very old, like seventy

i guess i’m falling apart, i’ll just

sew myself back together but will it last?

please take a piece of me back home, each piece

is anti-war and don’t pay your rent

A body, for Mayer and Spurlock after her, is relational. Like a book, it happens when there is a “you” to hand it to. This social gesture offers both pleasure and obligation: it takes a commitment to falling apart and refashioning the world, to which Spurlock asks the reader to “please contribute.” The world, and the poem, can’t happen without you.

LARB Contributor

LARB Staff Recommendations

Instruments of Unknowing: On John Lee Clark’s “How to Communicate” and JJJJJerome Ellis’s “Aster of Ceremonies”

Michael Weinstein reviews “How to Communicate” by John Lee Clark and “Aster of Ceremonies” by JJJJJerome Ellis.

No Forbidden Places: On Joyce Mansour’s “Emerald Wounds”

Ama Kwarteng reviews “Emerald Wounds” by Joyce Mansour.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2024%2F02%2FIn-Lieu-of-Solutions.jpeg)