The Ideology of the Everyday: The Wende Museum’s “Face to Face” Exhibition

By Oleg IvanovAugust 29, 2015

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2015%2F08%2FConcert-in-Weissensee.png)

THE WENDE MUSEUM and Archive of the Cold War is located in a nondescript office building at the end of a cul-de-sac opposite Holy Cross Catholic Cemetery in Culver City. “Wende” means “turning point” in German, a reference to the museum’s mission to preserve the communist culture of Cold War central and eastern Europe following one of history’s most dramatic turning points: the fall of the Berlin Wall and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union. The art and artifacts on display in the exhibition rooms represent a tiny fraction of the museum’s collection, which consists of over 100,000 pieces in a variety of media, from paintings and sculptures to flags, uniforms, furniture, and documents. The Wende’s library and storage facility, a treasure trove for scholars, contains works from both official and dissident/underground sources, often allowing researchers to compare responses to the same events from these opposing channels side by side. One can examine a socialist realist portrait of Lenin alongside a painting from 1989 comparing him to a “red bitch,” or an official portrait of Brezhnev next to a samizdat parody that accentuates the simian features and cartoonish proliferation of medals of the original.

Hungarian (signed with monogram H.A.), Brezhnev caricature, without date, oil on canvas

The museum’s newest exhibition, Face to Face (on display through September 25), offers a microcosm of the museum’s dual approach to Soviet culture, juxtaposing official products of Socialist Realism with works by artists working outside of Communist Party parameters. The works in the exhibit range from the immediate post-World War II era to the last years of communism in the eastern bloc. The earliest works are paintings that display an absolute fidelity to the precepts, manner, and political underpinnings of Socialist Realism. The subjects of these paintings fall into two main categories:

1) farmers surrounded with state-of-the-art equipment gazing heroically into the future with joy and/or determination;

2) old women stoically gazing into the future after having survived the deprivations of Nazi occupation and the loss of their sons and husbands.

In both cases, the political message is clear: the victory of Soviet communism over the reactionary and backward forces of the past is right around the corner.

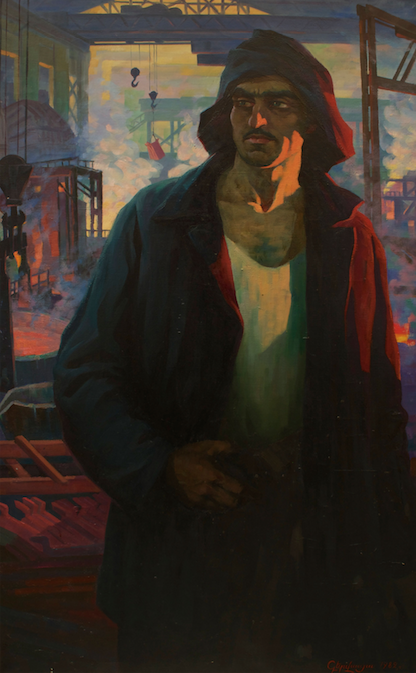

Gervasiya Vertanyan, Copper Smelter Ashot Restevanyan, 1982, oil on canvas

The conservative aesthetics of High Socialist Realism gives way to the more vibrant colors and increasingly impressionist manner of the 1960s, ’70s, and early ’80s, as embodied in the exhibition by two exemplary paintings from the period. Copper Smelter Ashot Restevanyan (1982), by Armenian artist Gervasiya Vertanyan, depicts its eponymous subject at work in a factory; the worker’s dark, shadowy form creates an otherworldly contrast with the background of pulsating neon tones. The painting’s ethereal atmosphere has more in common with 19th-century Symbolism than Socialist Realism. Portrait of a Girl with Heavy Fur (1977), by the Ukrainian Elena Vatslovna, shows a woman from the city of Vorkuta in the Komi Republic, north of the Arctic Circle, against an indistinct winter landscape. Ostensibly, the painting represents the ideal of friendship and brotherhood between the different Soviet Socialist Republics. The landscape depicted in the background is, on first look, almost indiscernible; close inspection reveals what could be a mountain range crossed by jet engine exhaust, but might just as easily be a river or a road.

Elena Vatslovna Yanchak, Portrait of a Girl with Heavy Fur, 1977, oil on canvas

The vague background is meant to emphasize the painter’s naturalistic rendering of the subject, one that ostensibly captures her “individuality” while simultaneously revealing “how art from socialist Eastern Europe was as diverse as its people,” according to the exhibition’s text.

A distinctly Western gaze informs the selection of these Eastern subjects, one that belies the curators’ argument, in the exhibit’s introduction, that the “idealized workers and farmers” represented in these quotidian scenes nevertheless capture “the individuality of those portrayed.” In fact, their individuality is denied twice over: the first time in the name of the political, and the second time in the name of the apolitical. If the painters idealize the Soviet people in the service of a simple political message, the curators do much the same thing by suggesting that the diversity of life in the eastern bloc can only be revealed by filtering out its political character. In effect, this replaces the overtly ideological worldview of Soviet communism with a Western tabula rasa, a seemingly apolitical image of “real life” that conceals within it its own underlying political assumptions about the realities of this world.

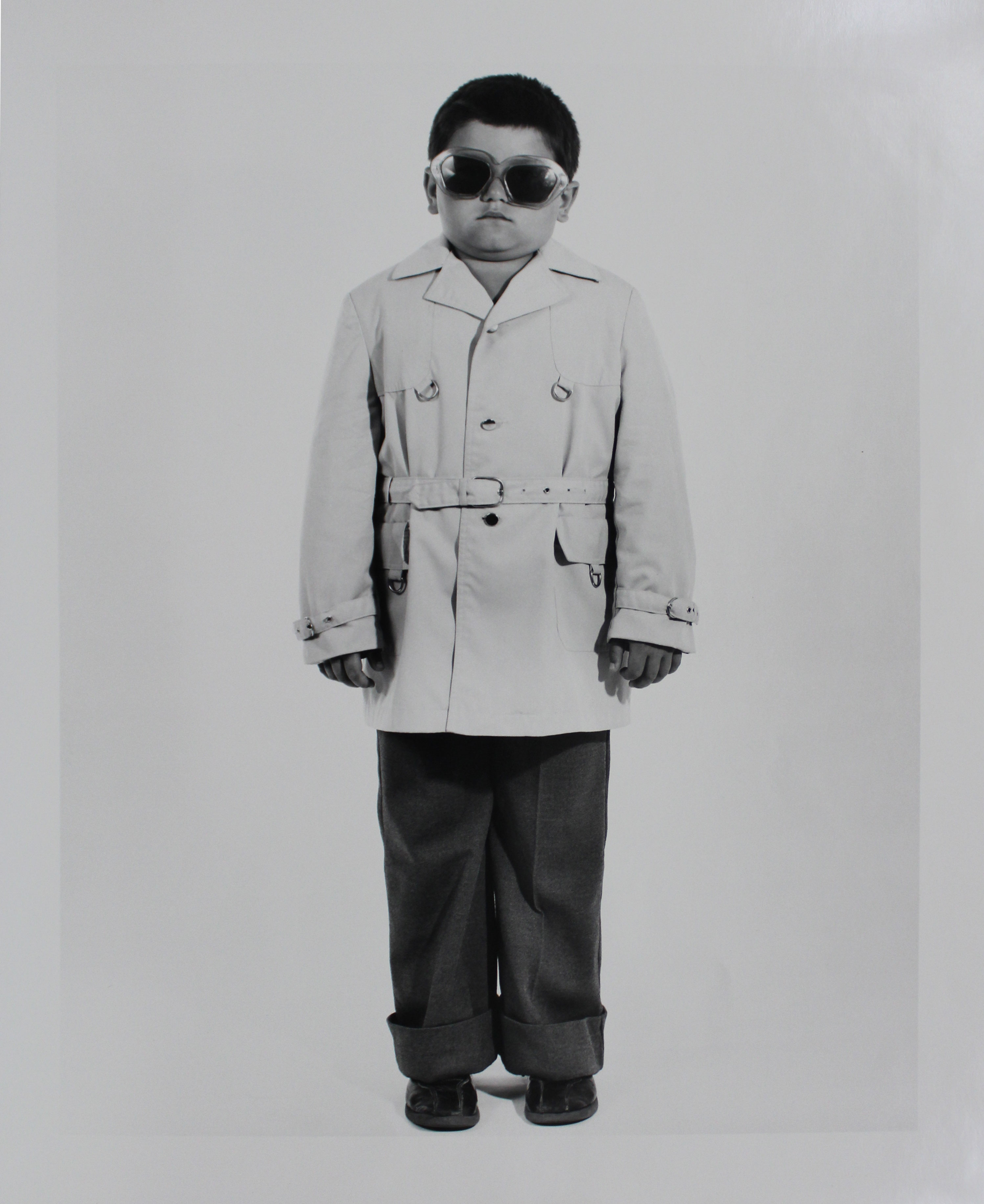

This kind of apolitical ideology is especially evident in the photographs of American Nathan Farb and the East Germans Claus Bach and Harald Hauswald. Farb’s Russians is a series of stark photographic portraits, black and white against a gray wall, of Russians that went to see the American photographer’s exhibition in Novosibirsk in the late ’70s (part of a cultural exchange program conducted during Jimmy Carter’s presidency). Farb snapped Polaroid photographs and gave the originals to his subjects, but, using a special technique of his own invention, also made negatives of these same photographs which he snuck back to America through an ambassadorial pouch. Despite the ostensibly “average” quality of his subjects, what Farb sets out to capture in these photographs is precisely their eccentricity and difference. One shows a laughing, overweight elderly woman in a sundress and kerchief with two full rows of gold teeth. Another shows a chubby child with a serious expression on his face; he is dressed like a secret agent, sporting a pair of wide-legged trousers, a long trench coat, and a pair of dark sunglasses.

Nathan Farb, Boy with Trench Coat and Sunglasses, 1977, polaroid photograph

According to the curatorial text, the child’s mother asked Farb to take his photograph for several days in a row, but the American replied that the child was simply not a very interesting subject. He only agreed to photograph him when the child arrived in this cartoonish getup, belying the curator’s claim that Farb’s work is a “candid … peek behind the Iron Curtain.” Contrary to the stated goals of Farb and the exhibition, it is precisely in emphasizing the otherness of his subjects that Farb captures the shared humanity that linked them to those on the other side of the Iron Curtain. Rather than candidly portraying average Russians, Farb instead manipulates his subjects to create a menagerie of eccentric, vibrant, and outlandish characters that undermine official depictions of life behind the Iron Curtain by authorities on both sides of it. Instead of an austere portrait gallery of proudly defiant workers and citizens, Farb’s black-and-white photographs, at once contrived and true to life, reveal the color and character of everyday Soviet existence. Farb’s camera captures his subjects simultaneously interpellated by two competing symbolic orders — Soviet communism and Western liberalism — and it is their placement at the intersection of these ideologies that gives these photographs an aura of authenticity. Beneath Farb’s aesthetic of candid simplicity lies the tension of two global empires locked in a struggle for ideological supremacy. In its own way, the pretense of providing an unfiltered view of Soviet life as an example of the West’s greater artistic freedom is as acutely political as the Socialist Realist paintings mentioned earlier.

The works of underground photographers Claus Bach and Harald Hauswald, according to the curators, “document life at the fringes of socialist society” in the German Democratic Republic in the late ’80s. Photographing “members of East-German society who were not represented in official art,” they too sought to present an authentic counter-narrative to state-sanctioned aesthetics, which championed representations of traditional (and, by this point, hollow and outdated) socialist values.

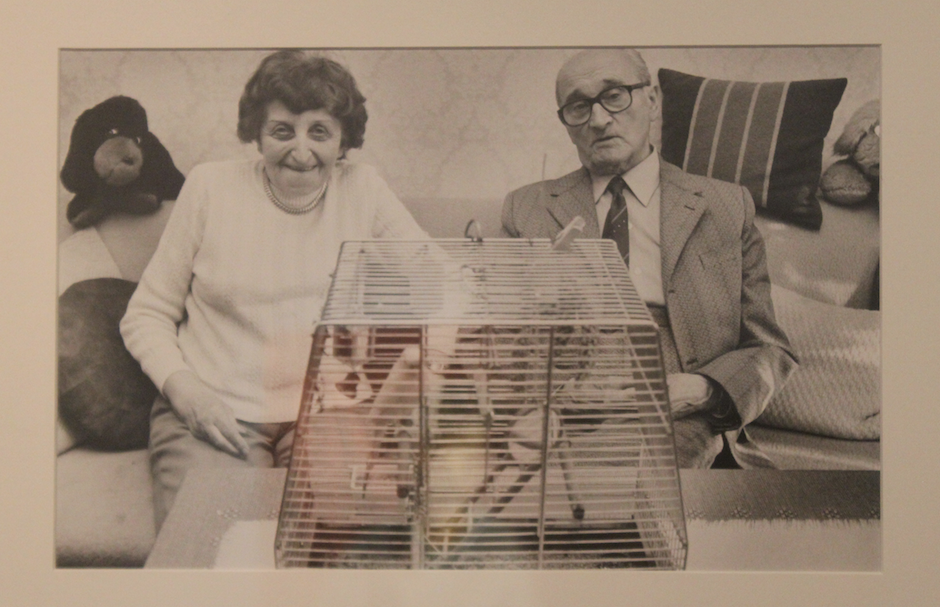

Claus Bach, from the series Pairs, 1986, photographic print

In the series Pairs, Bach photographed couples and housemates in their homes. What at first glance appears to be a simple premise meant to capture life under socialism without an ideological filter conceals the artist’s defiantly political stance. Bach allowed “his sitters to decide for themselves where and how they wanted to be photographed,” giving them ownership over their own representation in a manner that would be unthinkable in official art. While this aesthetic principle gestured toward the democratic liberalism that would soon supplant communism in Europe, it takes a great deal of effort on the viewer’s part to appreciate the photographs’ once revolutionary quality. Hauswald’s portraits of punks and hooligans feel similarly tame and even conservative in retrospect, as what was once a defiant gesture now comes off as merely voyeurism of the other, a GDR version of the hopelessly vapid photo blog Humans of New York.

Harald Hauswald, Concert in Weissensee, 1989, photographic print

Bach and Hauswald, like Farb, set out to show the lives of ordinary people behind the Iron Curtain, and their photographs share his mannered, politically apolitical tone. What appears at first glance to be politically neutral documentation of everyday life under socialism soon reveals itself as propaganda for a rival ideology, the official art of an underground that would become the establishment just a few short years later.

¤

Many of the dissident artists represented in Face to Face sought to undermine official communist ideology by depicting people outside of its dogmatic net, either as regular folks divorced from their socialist background or as outsiders abandoned by the system. But while these works reveal the state’s inability to fully encapsulate its subjects within its ideology, they also reflect the curators’ underlying nostalgia for a time and place when political art was of such radical consequence. This is typical of the Wende’s paradoxical project, which seeks to memorialize a lost way of life and the fierce resistance to it at the same time.

The first thing one is likely to see when visiting the museum is a vertical concrete block covered with a series of cartoonish faces painted in garish tones of blue, yellow, red, green, and orange. This is an original piece of the Berlin Wall that divided the western and eastern parts of the city, and the capitalist democracies of Western Europe from the communist eastern bloc, from 1961–’89. The painting was done by Thierry Noir, a West Berlin artist. While Noir did in fact paint on the Berlin Wall while it was intact, this particular mural was actually painted onto the broken segment of the wall after it came down in 1989; it is, in other words, a reconstruction of an earlier spirit of protest. Such nostalgic reconstructions are highly marketable; a block down from Checkpoint Charlie in Berlin — now a major tourist attraction — there is a Thierry Noir gift shop and art gallery. Perhaps it is the fate of all political art to end up as kitsch.

There is, inevitably, a nostalgic element to this preservation of Cold War culture and its discontents, one that seems to increase with time and distance for the participants of the era’s events. This is true of the dissident artworks in the museum that were initially made to protest an oppressive ideology: today, the celebration of these works contains an element of nostalgia for such protests, especially as they embody the lost youth of their participants. At the same time, even the works of official communist propaganda that the dissidents were protesting take on a sentimental tinge in this setting. As Milan Kundera wrote in The Unbearable Lightness of Being, “In the sunset of dissolution, everything is illuminated by the aura of nostalgia, even the guillotine.”

However, this aura cannot conceal that the principles animating countercultural depictions of everyday life outside the strictures of official state art behind the Iron Curtain have now become the region’s reigning ideology. Cold War dissident artists, activists, and intellectuals like Vaclav Havel, Lech Wałęsa, and Adam Michnik became important political leaders in their nations after the collapse of communism, guiding them toward the Western political, economic, and artistic freedoms embodied by the European Union. As these one-time nonconformists became members of the former communist bloc’s political and artistic establishment, the legacies of their movements became complicated by their complicity with power, and the ideology that gave rise to the period’s underground rebellion now shines forth from these works as transparently as that of Soviet communism does from the official art the dissidents set out to protest. What once appeared as “real life” looks, on museum walls today, like a different kind of propaganda.

¤

Oleg Ivanov is a freelance writer and PhD student in the Comparative Literature Department at UCLA.

LARB Contributor

Oleg Ivanov is a freelance writer and PhD student in the Comparative Literature Department at UCLA.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Muttnik: Canine Rocketeers in the USSR

Rigged with a faulty cooling system, Sputnik 2 was a lemon and killed Laika in three hours, frying her like Icarus.

When Gay Russia Speaks

A new book focuses on what gay Russians themselves have to say about being gay in Russia.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!