All photos courtesy of LA-Más.

WHEN DAVID DE LA TORRE opens his mailbox these days, he typically finds an offer to buy his home. Once, it was hand-written. Speculators canvasing the neighborhood are apparently a common sight — BMWs inching down residential streets, past modest single-family homes on small lots with low fences. Just a few blocks over, shrubbery leads up the hill to gridlocked freeway lanes. It’s comfortable here. Not quaint, manicured, or fussy. Quiet, but lived-in.

Elysian Valley — also called “Frogtown” — is sandwiched between the Los Angeles River to the east and the I-5 freeway to the west. Traditionally working class with a large immigrant population and, historically, a mix of residential and industrial uses, the 0.79-square-mile area has seen properties flip since the Army Corps of Engineers announced a year ago a $1-billion plan to revitalize the Los Angeles River. The investment would focus on an 11-mile stretch of the waterway, part of which passes beside Elysian Valley. With the city repositioning its river as an amenity rather than a flood control channel, the neighborhoods along its banks are receiving unprecedented attention. Property values are rising.

Factors like these leave certain Frogtown residents on edge. They’re worried about displacement. They’re worried about commercial activity coming in that won’t serve the community. (When De La Torre welcomed a new salon to Riverside Drive, he discovered that it charged $75 for a haircut.) They’re worried about density and height — developers building as big as they can legally go and dwarfing the one-story houses; about naked bike rides and eminent domain. Some of these fears are well founded (that naked bike ride really did happen — “a 200-nudist cycle parade down Blake Avenue,” said De La Torre). Others, less so. Regardless, there’s a sense in the community of losing control — that outsiders serving private interests will transform this neighborhood of about 8,900 into a place residents will no longer be able to recognize, or afford.

Certain property owners and developers in Elysian Valley — some long-standing, many newer — are eager to take advantage of the new market. Elysian Valley is just minutes from downtown Los Angeles, where revitalization has taken root after decades of failed efforts to bring economic activity back to a long-abandoned historic core. Mark Pisano, former executive director of the Southern California Association of Governments, has called the land along the river among the most undervalued in the county. He likens it to waterfront real estate.

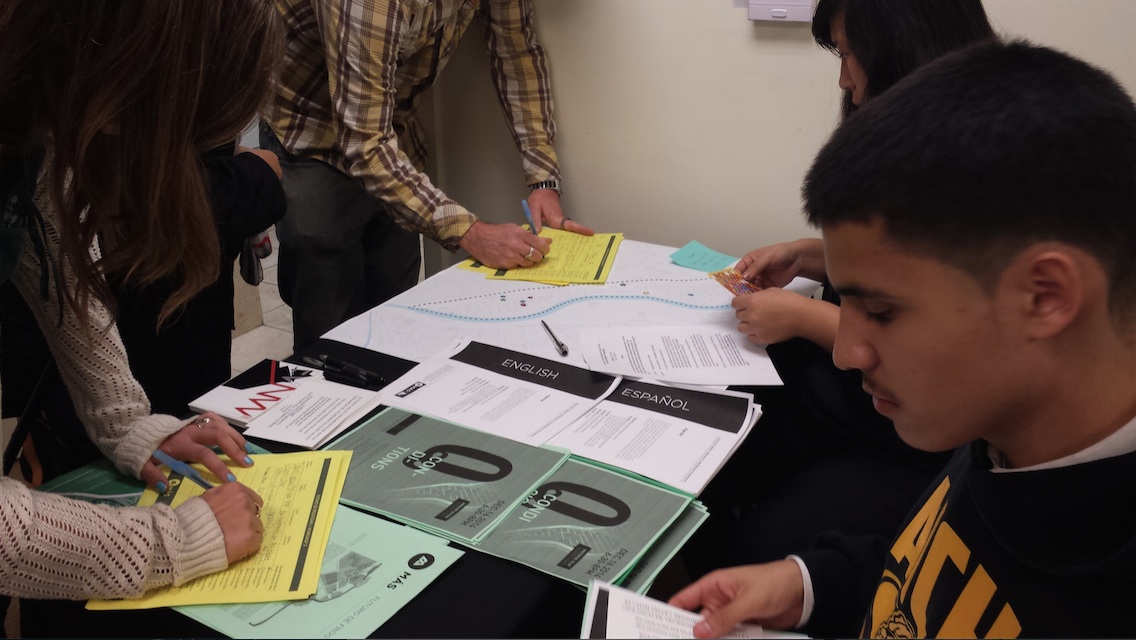

Enter LA-Más. The non-profit organization, co-founded by Elizabeth Timme and Mia Lehrer, launched the Futuro de Frogtown project in September to bring stakeholders into a strategic planning dialogue with one another. Through a “co-visioning” process, Más, as it’s called, sought “to redefine the existing paradigm of real estate developers versus community members” in a way that would “direct market forces to incorporate social and community goals into the development process.” Building on past participation in the 2013-2014 Northeast L.A. Riverfront District Vision Plan, Más held six interactive workshops intended to get beyond the kind of rote debate into which conflicts like these typically devolve.

Futuro de Frogtown encountered multiple and complex perspectives, including a group of community members opposed to change of any kind. This is nothing new: in Los Angeles County, neighborhoods have gained reputations for waging all-out wars to stop development, from Hollywood to Santa Monica. These narratives, whether in Southern California or in other regions nationally, often present community members as underdog heroes — struggling to preserve their way of life as 20-story condos rise up next to mom-and-pop grocers — or else selfish villains — NIMBYs standing in the way of collective progress because it blocks their canyon views. It’s not always so simple.

There are understandable, historical reasons why Frogtown residents might believe the only power available to them comes from impasse. For decades, the City of Los Angeles has had a less-than-exemplary relationship with communities like Elysian Valley. But the fight over Frogtown is more than an example of local power struggles taking place around the country. It also reveals the shortcomings a “no change” strategy can pose for residents seeking to protect their neighborhood. When calling for a standstill in the face of a shifting market, a community can miss the opportunity to offer alternatives that proactively meet its needs, ultimately leaving outside forces to determine the area’s outcome.

Given these dynamics, what would it take for traditionally disenfranchised populations to become real partners in guiding neighborhood change?

¤

Más held its third session last October at Framatic, in Frogtown. Folding chairs had been set up in the factory’s only clear area. Everywhere else, there were picture frames: piled high on shelves, leaning against each other, hanging off of racks, divided neatly into black frames and white frames, protected by cardboard and foam dividers. The owners, David and Edwina Dedlow, purchased the property in 1997 but had been in the neighborhood since the early 1980s.

Helen Leung, Más’s director of social impact and a co-leader on the project (along with María Lamadrid, design researcher for Más) explained why Más chose to hold the meetings at sites in the community rather than, say, in an auditorium at a school: “In addition to working with developers and property owners — in the sense that we’re using their space as an example and a microcosm of a larger issue — we’re inviting them to join throughout the process.”

About 25 attendees milled around as Más staff taped up five posters, each depicting a hypothetical future for the factory and the Dedlows. Participants used stickers to mark which scenarios they would choose, first imagining they were community members and next thinking like real-estate developers.

Timme explained the usual dynamics the project was aiming to get past: “There’s these two polarities that are both so reinforcing and validating for their own arenas: ‘Let’s keep everything just the way it is’ versus ‘I have all these rights to this parcel to make money, and if I talk to you about what I want to do, you are going to make it untenable for me to develop.’” This “completely co-dependent dance,” as Timme calls it, doesn’t result in satisfied communities, functional neighborhoods, or successful business.

Mott Smith, a developer who formed Civic Enterprise Development LLC and served as a consultant on the project, took the floor to ground each alternative in “market reality.” This meant opening up the brain of a developer and putting it on display: revealing the costs and risks someone looking to build in the area would consider.

A collection of pink and yellow stickers across the bottom of an option featuring affordable housing showed it to be a popular choice. But when Smith got into the details of what building affordable housing would look like in Elysian Valley, opinions changed.

First, in the example provided, the floor area ratio, or FAR, for the building was nearly 2, rather than the 1.5 maximum currently allowed. The FAR metric indicates density: how much total floor space can be built (including additional stories) compared to the parcel of land’s size on the ground. Smith explained why it was legal for affordable housing to exceed the limit: because of incentives provided by government to developers that build housing where rents coming in would be below market rate. This meant that affordable housing would be a denser use of a given lot than most other types of development.

Residents exchanged looks. Rick Cortez, the founder of the local architecture firm RAC Design Build, was seated in the back of the room. RAC Design Build had recently released a “smart growth” initiative that had garnered media attention, suggesting that the current density allowed along the river in Frogtown was too high and should be decreased. The Elysian Valley Riverside Neighborhood Council, along with many residents, was calling for the zoning rules to be changed in a similar manner to the initiative outlined by RAC Design Build. Here, however, they were confronted with a dilemma: looking at this example, limiting density would be at odds with promoting affordability. (Smith argues, as do many experts, that density and affordability are inherently linked in this way.)

Smith revealed another fact about affordable housing that troubled residents. Those currently living in a neighborhood are usually not the ones who will inhabit new affordable developments constructed there — first, because it would require extraordinary luck for an affordable unit to be available exactly when a local family wanted or needed it, and second, because legally, all income-qualified families have an equal right to affordable units, regardless of where they are from (affordable housing is allocated by lottery). While new affordable housing is good at preserving “census diversity” in an area, Smith explained, it wouldn’t do much to help the families currently there who wish to stay.

What had attracted participants to the affordable housing option in the first place was the hope that community members could remain in Frogtown even as land values skyrocketed. With this new information, residents largely preferred to attempt to keep the neighborhood as is rather than advocating denser, affordable developments. The top, articulated priority was preserving the physical appearance of the neighborhood — seemingly, at any cost.

“With ‘no change,’ there’s a risk of vacant businesses,” Smith warned. That prospect didn’t seem to worry the crowd.

One participant told the story of a friend whose property had been walled in by the new three-story RiverHouse development, which had created an L-shape around the home and blocked its view of the river. Residents shook their heads in concern.

Adaptive re-use, then, seemed like the order of the day: keeping the facades of the neighborhood intact. This option most closely matched participants’ stated desire to retain the built environment as is — although, were it implemented, it likely wouldn’t resolve many of the fears underlying that preference. Even if Frogtown’s skyline remains the same, its indoors and inhabitants may still change dramatically.

¤

David De La Torre met me at the Jardin del Rio community garden on Riverdale Avenue in a suit and tie. He had walked over from Sunday morning church services. After he unlocked the artisan-crafted gates — a metal mural of orange suns with mustachioed faces at their centers, an egret holding a fish in its mouth, dragonflies — we sat down under a gazebo. Numbered birdhouses, each a different color, marked the 28 plots tended by community members. De La Torre noted, “We have the true melting pot of America here. If you look at the sign outside this garden, it’s in four or five different languages. I have African-American, Japanese, Korean, Hispanic, Filipino, and Chinese gardeners.”

De La Torre started and heads the Elysian Valley Neighborhood Watch, which began out of a desire to decrease crime in the neighborhood by first reporting that crime to police. He has been an Elysian Valley resident for 35 years, has served on the neighborhood council, and attended the local elementary school as a child. “My neighbors have placed trust in me over the years. They can bring just about any issue to me — from how to deal with a water bill problem, to issues of social justice, tree removal, sidewalk repair, you name it.”

De La Torre noticed early signs of the changes to come starting in 2007-2008, when plans surfaced to pave the walkway alongside the Los Angeles River — long used by elderly Frogtown residents for constitutionals — in order to create a bicycle path. De La Torre lobbied then-City council member Eric Garcetti to maintain the walkway’s historical use.

“It did anything but that,” he told me. The city’s response was characteristic of what De La Torre terms “one of the biggest tragedies” — his perception that projects are “brought in here without true community engagement or coordinated planning.” The notion in Frogtown that elected officials aren’t operating out of respect for local wishes has been reinforced by experiences like these.

De La Torre explained the concern permeating the area as whispers of “gentrification” spread: “Here’s the fear: it is not of the people that are coming in. Elysian Valley is the most embracing of neighborhoods. The dynamics of its demographic makeup are proof of that. Dissatisfaction comes from the failure to recognize the characteristics of the neighborhood.”

He described the community as “middle income and blue collar” with “a large elderly, conservative, church-going population.” The area is also 60 percent lower-income Latino. As intensive river revitalization has become increasingly likely, De La Torre has noticed the impacts:

All of a sudden, it seemed that things were becoming hip that weren’t hip for this neighborhood. Marijuana dispensaries opening up just wasn’t hip. A nudie bar entertainment center isn’t hip to the greater population of this community, or a party element hosting weekday and weekend events. People are going to bed early to get up early for work, yet the neighboring business is holding entertainment that is noisy and inconsiderate, adds traffic, takes up parking spaces, and is a blight because you wake up the next morning not well-slept and with bottles on your front lawn.

The big question for De La Torre is whether Elysian Valley residents will benefit from the investments pouring in. The area still lacks basic infrastructure. There are no streetlights on as many as 10 blocks, and no sidewalks on some (like Blake Avenue) — fixes that he feels are urgent. Residents have also pointed to sewage issues and frequent electrical outages that need resolution.

De La Torre can see a potential upside for himself and his neighbors if the outside interest in Elysian Valley is channeled productively. He’s focused on bolstering existing businesses or supporting new enterprises using the skill sets in Frogtown:

A local licensed baker has come to me and said, “David, I want to set up a bakery opportunity here in Elysian Valley that not only makes my goods accessible to all, but also affords me the opportunity to employ within.” If that baker, who resides here and whose children attend our local schools, is not made a part of this winning formula, then this grand development will have failed.

¤

Before LA-Más embarked on Futuro de Frogtown, they set up office space in Elysian Valley, on North Coolidge Avenue at the Los Angeles River — because they wanted to be clear that they aren’t here for the short term or for superficial answers as part of due diligence.

“We were really passionate about offering an alternative model to community engagement that was not a mea culpa or ‘I’m doing this because it’s a box I’m checking off to be able to build a project,’” said LA-Más co-founder Elizabeth Timme.

A couple that lives in the area funded Futuro de Frogtown: Julia Meltzer of the non-profit arts organization Clockshop, and David Thorne of Elysian, a restaurant. Its name is a nod to one of their previous projects.

Adding to the local ties, project co-leader Helen Leung grew up in Elysian Valley herself. In high school, she helped with the formation of the neighborhood council. Given this history, along with her training in public policy and urban planning, Leung has opinions about the changes coming to Frogtown. So does Timme — she’s an architect. But in the spirit of the project, they kept these opinions to themselves.

Futuro de Frogtown’s six sessions yielded a document that went through community review. It summarizes the views articulated by stakeholders and identifies policy changes in line with those views. LA Más’s ultimate hope is that its outreach efforts and distillation of community preferences can help inform zoning changes currently under consideration by the City of Los Angeles.

In the time since Más began its engagement process, the city’s Planning and Land Use Management Committee approved a motion first introduced in February of 2014 by Councilmember Mitch O’Farrell, who represents Elysian Valley. It instructs staff to update the “Q,” or Qualifying, Conditions governing parts of Frogtown. Q Conditions place additional requirements or restrictions on properties beyond the specifications of that area’s zoning type and are outlined within community plans. The motion calls for changes in line with “preserving and enhancing the neighborhood character” and “seeking a higher degree of compatibility of architecture and landscaping for new infill development,” as well as allowing/incentivizing live/work units, adaptive reuse, and affordable housing. The Elysian Valley Riverside Neighborhood Council had begun requesting such adjustments in 2013.

The Department of City Planning has released a draft ordinance, and is scheduled to hold a June 9 public hearing on the matter. The proposed changes will pass through the Planning Commission and then on to the City Council, a process that could have new zoning regulations in place by the end of the summer.

(Los Angeles’s re:code initiative, conducted by the Department of City Planning and a zoning advisory committee, will rewrite zoning language across L.A. over the next four years to simplify it and eliminate complex requirements like Q Conditions. That means any adjustments made as a result of the motion would provide only a temporary “fix” for Frogtown.)

RAC Design Build’s call to decrease the building density allowed in certain parts of Frogtown (which is specified in the Q Conditions) is likely what propelled the motion forward. The architecture firm’s founder Rick Cortez garnered local media attention in October when he pointed out that Councilmember O’Farrell’s office had promised a solution faster than it was being delivered. This is an unusual circumstance. Architecture firms don’t often advocate more stringent limitations on what can be built.

Sitting in his studio’s kitchen last fall, across the street from Más’s space on North Coolidge Avenue, Cortez shared the worries that prompted RAC Design Build’s slow-growth initiative: Of the 30 or so riverfront properties in Frogtown, 15 had been bought up in the last 2.5 years, he explained. In the Commercial Manufacturing zone adjacent to the river, buildings can be about four stories high. As developers come in, the fabric of the built environment is likely to get denser and taller since current policy allows for that increased density, even though property owners historically have not taken advantage of it.

Cortez thinks that the land along the L.A. River should be developed solely for commercial use. Building residential towers there doesn’t make sense, he explained, because the river is really “a creek” for most of the year. Adding density along the edge of such a small body of water would be like “three photographers in the desert around a single poppy.”

Beyond the stylistic inappropriateness is a bigger question for Cortez: who feels ownership over the space? He fears that residential development there would give homeowners the sense that they had claim to the river as their backyard.

According to LA-Más’s draft project report, “developers are predicting that the market will support high-end residential use in the community.” That means intervention would be necessary to promote commercial over residential use — intervention in the form of policy.

As a player in L.A.’s built-environment scene, RAC Design Build can speak the language of city planning in a way that local residents can’t. To illustrate the future RAC Design Build wants to avoid, the firm created renderings using the currently allowed building density exercised to its maximum that showed a wall of four-story development along the riverfront, blocking access. Others in the field have called these renderings “misleading,” demonstrating a worst-case scenario with incorrect setbacks. This professional concern hasn’t stopped many in the community — including the area’s neighborhood council — from supporting the same decrease in allowed density that RAC Design Build proposes.

RAC Design Build seems concerned primarily with aesthetics. Cortez seeks “to make beautiful things,” he has said. If appearance is the driving concern, as it seems to be for Cortez, then changing the Q Conditions could make sense. But when non-architect residents want things to stay the same, they often mean a whole lot more than building setbacks. Since affordability is arguably at odds with keeping the built environment as it is today, community members must consider whether decreased FAR will lead to a neighborhood they can continue to inhabit.

Occidental College’s Mark Vallianatos believes that cutting the neighborhood's allowed density in half would be a “big mistake,” because doing so would limit the amount of new housing built there. Los Angeles downzoned in the 1970s and 1980s, he explained, which helped make it one of the least affordable cities in the nation. Vallianatos points to a recent report by the state Legislative Analyst's Office, which found that limits on housing capacity are the main cause of out-of control home costs in coastal California. He noted: “It may seem counter-intuitive, but the best chance for existing residents to retain a stake in their community is to make housing more abundant, both in Frogtown and throughout the rest of L.A. Unless we increase housing supply, rents will continue to rise, wealthier outsiders will outbid locals, and the children of current residents will be priced out of Frogtown.”

¤

The Q Conditions in question date back to the Silver Lake-Echo Park-Elysian Valley Community Plan update in 2004. Patricia Diefenderfer was the planner tasked with the area at that time. After studying Frogtown extensively, she explained, one of the plan’s main objectives was to create a neighborhood center at the site of what used to be a Bimbo Bakery and its environs. She noted that Elysian Valley lacked services and amenities — there had been only “one or two bodegas or corner stores, no retail or grocery stores,” among other problems. The Department of City Planning selected the Bimbo site to become a node for commercial use and public facilities to meet the needs of the community.

Back then, Diefenderfer recalls, residents did have concerns about density. She explained why the 1.5 floor area ratio — the current level — was eventually selected: “The community wanted to see investment, because investment would give them services and facilities. That wouldn’t happen if no one wanted to build anything. While scale is an important issue, if you limit what can be developed too much, nothing can happen. It wasn’t reasonable to constrain it beyond [1.5 FAR].”

Today, the Bimbo site is being developed as a small-lot subdivision project. The community still lacks a neighborhood gathering point. The desired commercial spaces and public facilities articulated in 2004 haven’t materialized. The neighborhood council’s list of desired additions to Elysian Valley include many of the same items Diefenderfer remembers: “library, community center, laundromat, grocery store, senior center, farmers’ market.”

An argument can be made that reducing the density permitted to developers would make those investments even more unlikely. Granted, the real estate market in the area has changed since 2004, and interest in developing there is now significantly higher. But if developers can’t build profitably due to stringent restrictions, interest could wane.

¤

By the final Más meeting, held at the Elysian Valley United Community Services Center in December, the conversation had become tense.

The building, a large shed-like space with a metal roof, used to be a sweatshop. It now houses a high school extension. An assortment of tables and their attendant supplies — stacks of geography and algebra textbooks, tubs of crayons, paint bottles, rulers — had been pushed back to set up the chairs and Más’s display. A TV, circa 1995, stood on a rolling stand under crests hanging on banners from the ceiling, and student art was pinned to the wall — yellow construction-paper turkeys made by tracing a hand. Weight-lifting equipment took up the front of the space on a stretch of carpet next to a mirror. Attendees ate lo mein and fried rice, courtesy of a long-time Chinese community member, as they talked among themselves.

The crowd was larger than the other meeting I’d attended — about 40 this time. Craig Weber, a senior city planner for Los Angeles, was attending in an unofficial capacity to observe, but obliged Leung’s request to offer an overview of the government process to update Elysian Valley’s Q Conditions.

When Weber was finished, a young resident standing in the corner raised his hand to ask: “How can we trust these meetings when they’re funded by developers?” From a book he was holding, he quoted some dense phrases about rights.

“I don’t know what you’re reading from,” Weber said.

The young man looked triumphant: “The State Constitution of California.”

The State Constitution doesn’t govern development, Weber tried to explain — the city’s General Plan and zoning laws do.

It was clear that the resident who had been reading was angry — but it was also clear that Weber wasn’t the cause. They were having two different conversations: the first, about a traditionally blue-collar immigrant community surrounded by “gentrified” or “gentrifying” neighborhoods, and the frustration residents experience when they see a future for their home that doesn’t include them; the second, about a technical city process for updating rules governing the built environment so that they better reflect residents’ desires. In theory, both Weber and the Constitution-reader were on the same team, but many of the participants didn’t see it that way.

It’s possible that emotions in the room were heightened because this was the final Futuro de Frogtown meeting, and some residents thought it would be their last chance to weigh in on the situation (it isn’t — as the city continues to consider revising Q Conditions, it will hold an official open house and public hearing) while others were ill-informed about eminent domain threats.

As Smith walked residents through scenarios in which different Q Conditions could promote specific types of development, many of those present resisted discussing the alternatives outlined. They instead expressed, again, that they wanted no change to how buildings look, the price of housing, the density of development, or the ease of parking. Even if improvements to infrastructure or the addition of services could come with development, these residents would prefer a standstill.

One group that has been vocal in the neighborhood does want to prioritize affordability — enough that they are willing to accept increased density (but not height) to accommodate it. When a participant spoke out on behalf of this approach, the room did stop and listen. But those who came in committed to preservation didn’t seem to budge. There’s a logic here: communities across the L.A. region that have taken a hardline stance against development have sometimes succeeded at slowing down particular projects, or making it untenable to increase density in a particular area through litigation.

But the problem with “no change,” and the crux of what bothered the Constitution reader, is that it isn’t actually a long-term option. A property owner could make no changes to her land, or the city could make no changes to the rules governing the area. But making no changes is not the same as stopping the area from changing. External conditions — river revitalization, rising property values, the real estate market as a whole, and the desire of millennials to live in city centers, among other factors — mean that Elysian Valley will probably change no matter how residents respond. Understandably, this reality can be difficult to accept.

In Smith’s words, the community does have the power to make certain paths of development easier or harder, like digging a ditch so that water is more likely to run down a particular path, by working in concert with city planners. Deciding which ditches to dig first requires imagining a future that’s different from today, but somehow positive or beneficial.

When zoning does not match the market, which can occur when residents want to stop realities on the ground from persisting, every development becomes an exception. It’s not that big projects don’t get built, Smith noted — it’s that they must go through long and expensive processes, but get built all the same.

“What about a community land bank?” asked Tracy Stone, a local architect who had hosted an earlier Futuro de Frogtown meeting at her live-work studio. There are tools outside the realm of zoning, Smith confirmed, that communities can use if they mobilize.

Stone’s suggestion didn’t get much attention that night, but it was a fresh example of trying to envision what the community does want, rather than reiterating what it doesn’t want, and coming up with options to get there.

¤

Futuro de Frogtown reached 1.65 percent of Elysian Valley residents. The effort achieved participation “slightly higher than other similar initiatives in the neighborhood,” according to Más’s draft report. The long list of strategies used to connect with residents, according to the project’s final report, include: “bilingual communications,” “paid advertisements,” “community partnerships,” “project website,” “door-to-door canvassing,” “bi-weekly open houses,” and “workshop markers.” De La Torre confirms that the makeup of participants was noteworthy: “LA-Más is the single group that has most genuinely made an effort to be inclusive in their outreach.” Still, the views of such a small cross-section of the community can’t be taken as representative.

For those who did attend, Más managed to bring developers and residents together so that they could engage not through contracts and ordinances, but face-to-face in the same room. Meetings were structured in a way that made tangible conversation most likely — providing multiple scenarios, seating participants in the spaces they would be discussing, bringing in Smith to moderate. Residents were exposed to ways of thinking about their neighborhood that, while foreign and even unsettling, educated them to the realities they face. Around less contentious subject matter — like formalizing the informal businesses in the area — the community did find consensus. Más recognized the diversity of opinions they were dealing with — a range of views more complex and broad than any one process (or piece of journalism, for that matter) could encapsulate.

What Más didn’t expect to grapple with, however, was the distrust leveled at the organization, despite its best intentions. At the closing celebration for Futuro de Frogtown, project co-leader Leung acknowledged this:

If we proactively and consistently told our story, perhaps so many individuals would not have misconstrued our interests and our intent. Our favorite examples include conspiracy theories that we were supporting eminent domain, encouraging high-density projects, or working for evil developers.

That context of fear informed the recommendations the project yielded. In the end, Más did advise the Los Angeles Department of City Planning to abide by residents’ articulated wishes: to consider decreasing the allowable density of buildings by half or further limiting their height, as well as directing buildings in the area to be used for commercial rather than residential purposes (along with a number of other findings).

Más must have found itself in a bind. The organization was obligated, based on the goals of the Futuro de Frogtown project it laid out up front, to pass along resident preferences to the city. But Más subtly acknowledges in its report that the community’s baseline wish at the heart of it all — to stay in Frogtown — might be adversely affected by limiting housing supply, implicit in the very recommendations it has offered: “If the above changes are enacted, the likelihood of new affordable housing in the community is significantly reduced and the community-wide impacts of the issue remain unaddressed.”

¤

Academic literature treats gentrification and displacement as two separate phenomena. According to Occidental College’s Mark Vallianatos, current research suggests that gentrification does cause some displacement but is offset by most residents liking the changes and trying to stay. “Low-education, minority, low-income, long-term resident and renter households do not exit gentrifying neighborhoods at greater rates than they move from non-gentrifying neighborhoods,” he stated. The existing residents who remain, Vallianatos said, “show larger income gains than residents of non-gentrifying neighborhoods” and “show larger increases in satisfaction with their neighborhoods than renters in non-gentrifying neighborhoods.” According to the research, he said, gentrification will eventually transform a neighborhood's demographics less by forcing residents out than by the barriers to entry that gentrification creates for low-income individuals who want to move into the area. All told, gentrification — rather than spelling the certain death of a long-standing community — might have a more complex impact than popular culture would have us think.

Still, Silver Lake and Echo Park are Elysian Valley’s neighbors. The ongoing narrative in Los Angeles and other major cities is of hipsters displacing long-time residents in urban centers. Plus, Frogtown is located close to Chavez Ravine — the site of Dodgers’ stadium and also the most infamous and dramatic example of eminent domain in Los Angeles. The displacement of Mexican-American families that occurred there in the early 1950s, in order to build public housing that never came to fruition, took place during the lifetimes of Elysian Valley’s older residents. It’s understandable that a fear of being pushed out runs deep.

But, no matter how understandable it may be, basing decisions on fear alone could prevent Frogtown inhabitants from engaging solutions that proactively steer development and investment.

¤

Since Más began Futuro de Frogtown, discussion of the Los Angeles River’s future has evolved — through a conversation mostly between land-use professionals, government, and academics, later picked up by the media (including some news coverage of Más’ process, spurred by its final report release).

Among the buzz is a new tool from Sacramento that is now under serious consideration for the area surrounding the L.A. River. Enhanced Infrastructure Financing Districts, as they’re called, would allow improvements along the waterway to pay for themselves up front, using bonds —based on the notion that such improvements will increase property values, and therefore ultimately increase property taxes collected by local government.

Last month, the Los Angeles Business Council reported that an EIFD focused on just the Northeast L.A. Riverfront — about five square miles, including Elysian Valley — could yield up to $217 million over its 45-year life (which means up to $31 million could become available in the near-term for spending, if bonds are issued). Those dollars would go toward infrastructure and redevelopment opportunities in that same area.

Such resources would provide Elysian Valley and its adjacent neighborhoods with a tremendous opportunity — for instance, a chance to realize the sewer upgrades and streetlight installations they’ve long clamored for. But an EIFD’s central mechanism relies on facilitating the rise of property values — accelerating the shifts in Frogtown that certain residents are determined to halt.

If an Enhanced Infrastructure Financing District does come to pass along the river, it may be the first of its kind in the state. That means the City of Los Angeles and its partner entities could help define — through practical experience — how EIFDs are viewed and used across California. And if successful, productive community engagement came to pass in waterfront neighborhoods as part of an EIFD, it could set a significant precedent.

With enthusiasm for river revitalization brimming across the city this year, many Angelenos have heard promises of the public good to come as we renew our aqueous artery. As elected officials champion this transformation and the catalytic potential of an EIFD, it is that same leadership’s responsibility to act on behalf of citizens in close quarters with the river who stand to benefit or suffer.

Futuro de Frogtown revealed that even sensitivity, thorough research, and a deep knowledge of the issues might not be enough in the face of a community’s historical relationship with government and development. If the municipality does want residents’ trust over the course of river revitalization, what can it do to prove worthy of it? How can those in power and those who feel powerless both create the conditions where collaboration is possible?

¤

Molly Strauss is editor of The Planning Report and a writer in Los Angeles.

LARB Contributor

Molly Strauss is editor of The Planning Report and a writer in Los Angeles. She is on Twitter @mmstrauss.

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Tale of Two ’Hoods: A Rap on Silver Lake

Silver Lake: a correspondence.

Seeing Water in Los Angeles: On Lethe’s banks

Los Angeles's riparian history

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2015%2F06%2Ffrogtown-feature.jpg)