ALL OF THE DEBATES — is True Detective a sexist show, or a show about sexism? A plagiarized show, or an original postmodern show? — miss the crucial point. True Detective is a show about HBO shows. Certainly not a feminist show, and not a postmodern show about the nature of systems themselves, but a show specifically about the brand of HBO on cable TV. This is why no one can decide whether there’s any there there. The show is about itself, about cable TV at the moment of the unbundling of the cable pipe. [1]

Cable TV right now is the scene of a struggle for cultural capital. Whether or not HBO has a lock on quality, it is where the debate over American cultural quality lives. That feels important, so the show felt important. It also left many of us feeling vaguely duped, as if perhaps sophomoric philosophical rantings and lush Southern locales had been used to repurpose yet another buddy cop duo solving the rape and murder of a pretty young white girl, as if perhaps the show were empty at its core.

You barely have to scratch the surface to see the show’s focus on choice, pipelines, and televisual technology. This show came out right after HBO Go and right before HBO Now, the first step toward streaming on-demand delivery of HBO shows. True Detective season one is of and about the first moments of a landscape that will test HBO’s brand as it has never been tested.

Call to mind the show’s imagery: The river, and the way that the crimes are bundled around that pipeline. Remember all those long loving shots of telephone wires? All the lush visuals that immersed us in communities lacking in basic technology? Those shots asked the audience: How will they ever get cable? The primary evidence for the crime in True Detective season one was a videotape that would get distributed only if the detectives didn’t come back from their last foray. The audience never got to see the actual content of that tape, another meta-fictional show. True Detective reminds you that you want to see the tape, and reminds you of its own power to broadcast or withhold the true crime.

Early in season one, Hart brought his mistress handcuffs because he thought it would be sexy to chain her up. She chained him up instead. Hart thought he wanted to handcuff someone else, but what he really wanted was to be handcuffed. This was the show’s basic playbook. You know you want it.

The “it” that the audience is always being reminded it wants is quality cable, and the show’s many many references go beyond Pizzolatto’s bookshelf to the fight between AMC and HBO. This was the hidden payoff of the show’s self-reflexivity. The title sequence and the show itself are chock-a-block with references to other quality cable shows, from the unnecessary Breaking Bad reference (where a drug dealer walks out in his underwear and a gas mask as a prequel to which the action will return) to its title sequence callbacks to AMC’s Mad Men, and HBO’s True Blood and Game of Thrones. Pizzolatto used to write for AMC’s The Killing, the other moody, lush, kinda disturbing cop show that was supposed to be not like other cop shows. Watch the title sequence again. The references are unmissable once you’ve noticed them.

The whole show is about pipelines and technology, choice and contract. Detective Hart’s crime, according to his wife Maggie, is that “he never really knew himself, and so he never really knew what to want.” Immediately following that accusation, Hart goes to a T-Mobile store. The location is gratuitous. It is the place where, coincidentally, a prostitute from the “ranch” he and Cohle had visited on their search now works. The camera lingers on the T-Mobile logo and the map of the United States. T-Mobile, of course, is a digital cell phone company famous for its lack of binding contracts.

The girl who looms up and out of the T-Mobile logo was the prostitute Hart tried to help, earlier, on the bayou. As Hart gazes into his new phone in a nearby bar, the girl follows him and sees that Hart has bought tampons. She asks him if he has a fun weekend planned. Hart, it’s implied, is buying tampons for his wife and so won’t be able to choose sex this weekend. The tampon is the visible symbol of the binding, monthly contract that Hart has entered into with his wife. The T-Mobile prostitute represents freedom from all that. Hart doesn’t know what to want, so when offered too much freedom, he chooses wrong. He cheats — he loses his beautiful wife.

Notice, again, his wife’s choice of words: “he never really knew what to want.” It’s not that he doesn’t know himself. He wants to keep his wife. A correct choice exists. It’s about the circumstances under which Hart can see what he wants. He needs that contract; when he throws it off, he loses everything.

Cohle, meanwhile, is overburdened by human freedom. He sees clearly the existential weight of choice: “We became too self-aware. Nature created an aspect of nature separate from itself — we are creatures that should not exist by natural law,” he tells Hart. “I think the honorable thing for our species to do is deny our programming. Stop reproducing, walk hand in hand into extinction — one last midnight, brothers and sisters opting out of a raw deal.” (The idea that humans should honorably march into extinction comes from Ligotti.) Hart makes the wrong choice by opting out of his monthly contract, but Cohle never entered into a contract — he is full of the painful self-awareness of freedom, the nihilistic extinction that comes of leaving the whole package of human drama, of “denying programming” and “opting out.”

Cohle goes to visit Reverend Billy Lee Tuttle, a stand-in for televangelist Jimmy Bakker and as such a symbol of the heyday of 1980s broadcast television. “Well Spring” is the school program that becomes central to the case, which also covers that period: broadcast is the source of the mystery, a wellspring, the original source for the pipeline. Cohle asks Tuttle about the schools, which, like televangelists and broadcast quality, have all but disappeared. The Reverend brings it back to choice: “People should have a choice in education like anything else.” Strange words for a presumably pro-life minister. But some choice is false, a televangelist wolf in sheep’s clothing.

This conversation leads directly to Cohle’s suspension at the police department. His suddenly outraged superiors say: “You don’t get to decide what kind of conversation it was,” and then end his contract, for one month. As the major abrades Hart, he calls him a “human tampon,” which recalls the T-Mobile scene. The words make central Hart’s inability to be the right kind of man on a monthly contract.

Cohle, in his existential exemption from contracts, seems to be plugged into the network through his brain. He’s the future. He is HBO Now, anywhere anytime. His visions never go away, he’s burdened by always seeing it all, the whole HBO universe, just beyond his eyeballs. It’s dangerous, this new reality.

In the final episode, Hart and Cohle drive off the grid, into a lush forest. Cohle says, “This is the place.” And then he tells Hart, “Ask to use the phone.” Marty, who is not plugged into the network through his brain, has to go find the landline.

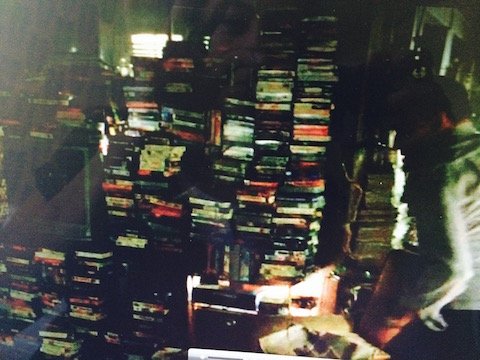

The terrible Childress house is a hoarder’s lair, derelict and full of dinosaur technology: books and VCR tapes. The old vacuum-tube television is an important visual centerpiece. The incestuous sex scene occurs in front of all those videotapes, because no cable means perversion and endogamous choice. When Marty has to clear the house and find the phone, he stops, bewildered, in front of this terrifying stack of VHS. But remember the lingering shot that established telephone poles alongside the leafless trees in the bayou. The pipeline taketh away and it giveth.

The terrible Childress house is a hoarder’s lair, derelict and full of dinosaur technology: books and VCR tapes. The old vacuum-tube television is an important visual centerpiece. The incestuous sex scene occurs in front of all those videotapes, because no cable means perversion and endogamous choice. When Marty has to clear the house and find the phone, he stops, bewildered, in front of this terrifying stack of VHS. But remember the lingering shot that established telephone poles alongside the leafless trees in the bayou. The pipeline taketh away and it giveth.

The cable pipeline is both threat and savior — the thing you don’t know you want, the thing you can’t admit that you want, that you can have too much of. HBO programming is the tape you both don’t want to see and are desperate for.

The cable pipeline is both threat and savior — the thing you don’t know you want, the thing you can’t admit that you want, that you can have too much of. HBO programming is the tape you both don’t want to see and are desperate for.

¤

Because the show is about HBO and cable itself, it prompted a mise en abyme of huge claims about the show’s genius alongside total pans, critics chasing their own tail and enjoying it. But the somewhat bizarre Vanity Fair profile of Nic Pizzolatto that just came out is a special case. The writer compared Pizzolatto to David Milch. Whatever you think of this compaison, Milch has a long and storied history of television successes. He is the original television auteur, and Pizzolatto is nowhere close. The comparison serves primarily to get readers invested in the question of whether season two can catch up to this Hail Mary pass.

The Vanity Fair profile is a kind of masterpiece of casuistry and hagiography. Its author writes of Pizzolatto: “When I was a boy and dreamed of literature, this is how I imagined a writer — a kind of outlaw, always ready to fight or go on a spree” (friends on Facebook joked that guru kings like Pizzolatto are “born with whisky in their blood like 12 point courier down a page”). In its purple prose, the profile helped along the process of branding HBO as the auteur-generator: “If he fails and the show tanks, he’ll be just another writer with one great big freakish hit. But if he succeeds, he will have generated a model in which the stars and the stories come and go but the writer remains as guru and king.” The plot and the actors and the show itself matter not. What matters is some essential and essentially vague (and therefore reproducible) quality — the quality of emperor auteur, the HBO brand.

When we realize that the emperor has no clothes, we learn something about ourselves (I was duped!) and about the emperor’s mind (he was foolish!). Once we realize their absence, clothes still seem important (because, cover that shit up). If we all decide that Pizzolatto was foolish and we were duped, his status may suffer, but HBO’s brand as the arbiter of status will remain intact. HBO still gives out the clothes. And that, ultimately, is HBO’s goal: it can’t always promise quality, but it can promise to remain the testing ground for quality, the scene of cultural capital itself.

True Detective season one was the culmination of a process where a self-referential debate over where “quality” lives has replaced quality itself. In a forthcoming essay on True Blood, True Detective, Veep, and Silicon Valley, Michael Szalay reads HBO programming as reflexively preoccupied with the distribution technologies through which the network disseminates its brand in an era define by direct internet delivery. On the one hand, HBO co-president Richard Plepler has assured viewers, “We’re not determining success on the basis of numbers. We’re determining success on the basis of quality and we believe the numbers will follow.” But at the same time, David Simon, the creator of The Wire, maintains that if his masterpiece were being pitched today, HBO would pass on it. He blames the industry’s new and “slavish devotion to audience metrics.” In the new on-demand reality, producers can see the exact moment when fans stop watching (like 30 seconds into Netflix’s House of Cards pilot, when the dog dies). It’s not yet clear how this will affect risky storytelling. But post The Sopranos and The Wire, it is clear that HBO needs both lots of eyeballs and the association with quality that make people pay for its brand. In what some critics are calling “TV III”: “By building an identity that is separate from the physicality of a conduit, HBO may survive as a brand long after it has lost its relevance as a premium channel.” [2]

True Detective season one was about cultural production in light of HBO’s brand, but also in light of this new technological reality. The lure of HBO prestige is the promise that audiences can garner some of the cultural capital that once came from reading the right poetry or the right novel. At the same time, on-demand television means a deep and undifferentiated pipeline, a wellspring of constant stuff to watch. We want to feel the gratification of having had the best, most discerning taste and at the same time we want a universe of programming in front of our eyeballs at all times. True Detective season one mocked us for wanting both quality and quantity, it was a go-away come-here about our own love of HBO and on-demand.

The Vanity Fair profile attempts to brand Pizzolatto in advance of season two. It says that he withdrew his first novel himself before it was about to be published. The implication is that he was not convinced of his own seriousness and quality as a writer, but that he was therefore a more serious arbiter of quality than his literary publishing house. The reporter sums up Pizzolatto’s decision not to publish with a sentence fragment: “Because screw this and hell no.” The question of Pizzolatto’s actual literary quality is thus replaced with an energy-drink tagline. Pizzolatto is in the process of becoming a brand. As a symbol of seriousness and quality, or as a symbol of the quest for seriousness and quality, he will continue to let HBO tell its story through him. Season one did this at a crucial moment when HBO was desperate to tell its audiences how to stay with the brand while leaving the contract.

Season one taught audiences to feel original by thinking about our unoriginal feelings about wanting something new. It was a meta-show about being a meta-show. Like Cohle, we want to “deny our programming and opt out of the raw deal” that is cable bundling’s iron grip. Like Hart, in the end we need to learn that opting out of the contract completely is a bad choice. We may or may not, with season two, see that the emperor has no clothes. But it doesn’t matter, as long as we keep asking: who is the next emperor, the next auteur? HBO could care less whether True Detective season two is actually quality original programming. The Home Box Office could care less if we say “screw this and hell no” to Pizzolatto’s next project, as long as we turn to HBO to pass the mantle to the next guru king.

¤

[1] Just before the Emmy Awards, a minor controversy erupted about whether the original show creator Nic Pizzolatto had plagiarized. The most direct verbal inspiration, for many turns of phrase if not quite plagiarism, came from Thomas Ligotti’s “The Conspiracy Against The Human Race.” The name “Carcosa” comes from an Ambrose Bierce story; “The Yellow King” from Robert Chambers. Pizzolatto’s original reactions seemed almost as if he had something to hide, instead of just embracing all the Easter eggs he had planted for literate viewers, but ultimately the idea that he was at fault didn’t stick.

[2] Michael Epstein, Jimmie Reeves, and Mark Rogers, “Surviving the Hit: Will The Sopranos still sing for HBO?” in Reading The Sopranos, ed. David Lavery, Palgrave MacMillan 2006.

¤

LARB Contributor

Michelle Chihara (MFA, PhD UC Irvine) is the former editor-in-chief of the Los Angeles Review of Books. Her fiction and nonfiction have appeared in Studies in American Fiction, n+1, Trop Magazine, Green Mountains Review, the Santa Monica Review, Echoes, Mother Jones, and The Boston Phoenix, among others. Her research involves real estate, financial panics, and contemporary culture. You can find her online at michellechihara.com.

LARB Staff Recommendations

You Can’t Make a Living: Digital Media, the End of TV’s Golden Age, and the Death Scene of the American Playwright

Digital Media, the End of TV’s Golden Age, and the Death Scene of the American Playwright

Gilding the Small Screen: or, “Is it just me or did TV get good all of a sudden?”

The true reasons for TV’s emergence as the preeminent mass medium of the early 21st century are primarily external to the actual business of creating...

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2015%2F06%2Fposter.jpg)