All photographs published with the permission of Bukhara Magazine. All rights reserved.

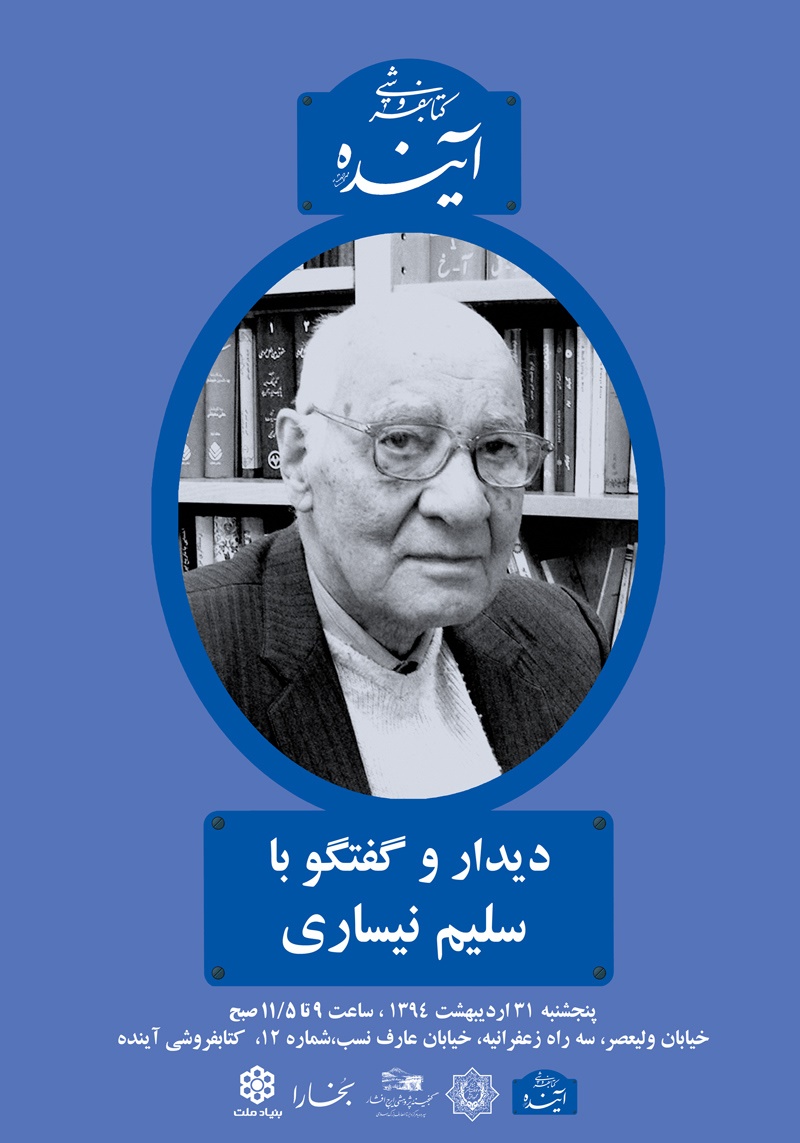

IT’S 9 A.M. on a cool but sunny Tehran morning in the spring. We sit in a corner of a garden in Bagh-e Ferdows, upper Valiasr Street, one of the only few homes of the early Pahlavi era that have not yet been razed to make way for an apartment building, or a high rise. There are sycamore trees all around us, once ubiquitous in the vast orchards that ran through this area. Every now and then two of the cats that frequent the garden casually pass by, their tails curved in the air. Ali Dehbashi, editor of Tehran’s Bukhara magazine, begins his conversation with scholar Salim Neysari, facing an audience of about 60, sitting on stone steps made into an open-air auditorium. Water, tea, coffee, and an assortment of pastries are offered in a corner.

Salim Neysari is 95 years old. His career spans 70 years as an administrator, dean, writer, researcher, and academic. He is also a keen reader of every existing manuscript of Divan-e Hafez, which total 48, and can effortlessly run through verses that differ from manuscript to manuscript. Nearly 500 ghazals make up the Divan of Hafez, all composed by the 14th-century poet who is perhaps the most widely read throughout the Persian speaking world. Verses in a number of his ghazals are common proverbs or sayings in the Persian language, including the first verse of the opening poem: “Keh eshgh asan nemood aval vali oftad moshkelha” — “Many hardships await on the path of love, that at first glance, showed to be simple.”

As Neysari begins to speak, the sound of a cane alerts the audience to a new presence. Even from the corner of our eyes we can spot that signature beard, flowing like a waterfall. The poet Houshang Ebtehaj, whose pen name is Sayeh, walks in with small, hesitant strides. Starstruck and giddy, we all want to look his way, but that would be disrespectful to the speaker. Neysari himself solves the dilemma, looking toward Sayeh and welcoming him warmly, while Dehbashi asks one of the volunteers to take him a chair. Days before the event on a social media, some speculate that Sayeh might be here today given his friendship with Neysari. But he rarely makes public appearances, so members remained undecided.

Ebtehaj is Iran’s most celebrated living poet. For 60 years, he has been both political activist and prisoner, involved with the leftist literary movement, revolution, and exile. In the early 1950s, along with poets Morteza Keyvan and Siavash Kasrai, he formed a social, political poetry circle that became both celebrated and widely read. Keyvan played a central role in connecting young leftist poets and intellectuals of his day. Sayeh, Kasrai, Mehdi Akhavan-Sales, and Ahmad Shamloo, among others, found their beginnings in his literary gatherings and vividly recall his cultural influence. Keyvan was the only civilian executed following the 1953 coup which ousted Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh. He was 33 years old. Sayeh writes of Keyvan’s unmarked grave: “Oh dear of my heart, which sycamore are you?”

Ebtehaj is Iran’s most celebrated living poet. For 60 years, he has been both political activist and prisoner, involved with the leftist literary movement, revolution, and exile. In the early 1950s, along with poets Morteza Keyvan and Siavash Kasrai, he formed a social, political poetry circle that became both celebrated and widely read. Keyvan played a central role in connecting young leftist poets and intellectuals of his day. Sayeh, Kasrai, Mehdi Akhavan-Sales, and Ahmad Shamloo, among others, found their beginnings in his literary gatherings and vividly recall his cultural influence. Keyvan was the only civilian executed following the 1953 coup which ousted Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh. He was 33 years old. Sayeh writes of Keyvan’s unmarked grave: “Oh dear of my heart, which sycamore are you?”

More than any other contemporary poet, Sayeh is referred to as the “Hafez of the age.” In 1967, at the Shiraz Arts Festival, he was scheduled to read his ghazals to an anticipating crowd waiting at the Mausoleum of Hafez. Travel writer and historian Mohammad Ebrahim Bastani Parizi later recalled that he had never before “seen audiences so welcoming and receptive to new poetry.” Neysari points to him when he is asked who he believes to be Iran’s greatest living poet. But this is far from a settled argument. Editor Manuchehr Anvar once commented during his own talk weeks before: “Persian literature stopped producing giants like Hafez long ago. We must now talk amongst ourselves in the world of dwarves.”

More than any other contemporary poet, Sayeh is referred to as the “Hafez of the age.” In 1967, at the Shiraz Arts Festival, he was scheduled to read his ghazals to an anticipating crowd waiting at the Mausoleum of Hafez. Travel writer and historian Mohammad Ebrahim Bastani Parizi later recalled that he had never before “seen audiences so welcoming and receptive to new poetry.” Neysari points to him when he is asked who he believes to be Iran’s greatest living poet. But this is far from a settled argument. Editor Manuchehr Anvar once commented during his own talk weeks before: “Persian literature stopped producing giants like Hafez long ago. We must now talk amongst ourselves in the world of dwarves.”

Walking in with Sayeh and later sitting to his right is Mohammad-Reza Shafiei Kadkani, a poet and one of University of Tehran’s most distinguished professors, and a scholar of medieval Persian Sufi manuscripts. Students from all across the country travel to the capital to attend his classes at the University of Tehran. During lectures, they sit on the floors, by the doorway, and on the window sill, often leaving him no place to go other than his desk (his chair is first to be given out to one of the standing students). His revision to more than 20,000 verses of mystical narrative poetry by the 12th-century Sufi poet Farid ud-Din Attar of Nishapur was published in recent years to wide critical acclaim. The multi-volume project includes a thousand pages of commentary in addition to the poems. Kadkani meticulously traces the sources of Attar’s poems to earlier books, stories, and mystics, and describes the roots and meanings of Sufi expressions, making Attar’s words accessible to a new generation. Rumi, who is more widely known and read in Iran and the West, writes: “Attar has traversed the seven cities of love, while we are only on the first street.”

The most accomplished of Iran’s students go to schools of engineering or medicine today. Kadkani was educated during an era where his overachievement (he could recite Ibn Malik’s 13th-century book of Arabic grammar by heart at the age of eight) led him to poetry and literature. He holds a stature of unparalleled admiration from the public, so much so that when he left Iran for Princeton in 2009 following the contested elections in June of that year, it was the gravest sign of what Iran had become: even Shafiei Kadkani would leave now. Rumors circulated that he would never return. And perhaps, that he did return a year later, was also a sign of how that Iran carries forward.

Salim Neysari has never before granted an interview, nor has he given a public talk. Kadkani and Sayeh are not seen at Tehran’s increasing number of book readings and cultural circles. Only one man can bring together artists, scholars, and writers of this caliber: Ali Dehbashi. Here, he is in his element, his lips curve in a smile of satisfaction; his usually worried eyes are calm. He has spent a lifetime cultivating relationships that would make this day possible — both for speakers and audience. Since his career began as an editor in the 1970s, Dehbashi has cemented his place as “the lover of the Persian language, across political borders,” as he is called by many who know him. He has also provided a gathering space for the artists of this language, and its legacy, to be presented and explored. In tandem with such efforts, he publishes what remains Iran’s most influential literary magazine: Bukhara.

The late Fereydoon Moshiri, whose poetry President Obama cited in his 2016 Nowruz message, was one of Iran’s most beloved writers. In 2000, just months before he died, he spoke at a ceremony marking the third year of Bukhara’s publication. He described how Ali Dehbashi singlehandedly publishes the magazine, nafas nafas zanan, always short of breath due to the severe asthma that Moshiri has seen “from up close.” “His right shoulder is always bent due to the weight of the bag he carries,” Moshiri continues, while pushing his right shoulder down with his left hand to show how Dehbashi stands with his signature shoulder bag, his “office, archive, library, and editing desk.” Like most other people who mention Dehbashi, he reminds the audience of the price the editor pays to bring each issue of the magazine to publication, one that he always anticipates: “I sit there, asking whoever walks in if it is in the mail.”

Ali Dehbashi rents a house on the first floor of a four-story apartment building — which currently serves as both his residence and the Bukhara office in downtown Tehran. The front door is open during visiting hours, early mornings, when I drop by every now and then. A hallway leads to a yard where dozens of tiny pots of flowers, either on the ground or on wooden stools are aligned in neat rows. He attends to the plants daily before heading out of the house. At the end of the yard, on the right, there is a door leading to the unit which serves as his home and office.

Inside, staring eyes confront the visitor in every direction: wide-eyed owl figurines made of sea shells, wood, ceramic, clay, metal, and straw. They hang from shelves and cases, or hold on to dear life from the outer most edge of a table — what can be seen of a table that is, upon which lie hundreds of pages of paper, books, and manuscripts. Long wooden bookshelves cover the walls from floor to ceiling in the living room. On the upper shelf of every case, fine leather-bound issues of magazines Dehbashi has edited, including Bukhara, shine with gold and green calligraphy. In front of each bookcase, a collection of folders, boxes, and more books are scattered. I spot a portable oxygen tank and inhalers in between the piles, hinting at how this chaotic calm can be instantaneously shattered. Photos of Dehbashi and writers and poets hang in various corners of the living room. One shows a much younger (and much thinner) Dehbashi gleefully smiling at the late Akhavan-Sales. He tells me that he has an archive of thousands of these photos in storage.

Copies of the French literary magazine Le Magazine Littéraire, a book of photos of Ernest Hemingway, and The Ultimate Book of Pens (Dehbashi collects fine pens) are among the other publications casually thrown around. Dehbashi knows exactly where everything is, and can effortlessly reach out and take a sheet of paper lying unseen beneath the stacks. Among the piles, visitors can find a stool or a chair or just an empty place to sit. Dehbashi warns guests about making a mess.

During the cold season, a thin camel-colored wool blanket hangs from Dehbashi’s shoulder as he moves from one part of the room to the other while receiving company, mail, editing or proofreading articles, and responding to phone calls on his cell. He does not use headsets on his phone, but instead chooses to put the phone on speaker and hold it horizontally in his right hand.

A student calls to say that he has gotten Dehbashi’s number through a professor, and needs help with a thesis on “how modernity is represented in Persian novels.” Dehbashi questions the student to get more details, in the process also quickly assessing the student’s knowledge and interest. He ends the conversation when he concludes that that the caller does not have much to offer, instead wanting Dehbashi to do his homework. He looks at his phone with disgust after hanging up. “This new generation is shallow in every aspect. I ask for details and he says he has to hand in the thesis in three months and, ‘oh I want to know about story writing in general.’”

Dehbashi doesn’t always pick up his phone. If he purposely does not answer someone and they call back, he will have a word or two with them. He barks angrily at one caller who has phoned three times in less than two minutes: “Maybe I can’t pick up the phone right now, hasn’t anyone taught you to not keep calling?” Journalists phone him often, a group with which he sometimes has tense relations. “An arts journalist working for a prominent paper once called me to inform me of an event,” he says, “naming Virginia Woolf as one of the guests — that’s the state we are in.” While I am sitting there one day, a reporter from a local news agency, a young woman, calls him and asks him to double-check a story she is running about a reading he recently hosted. He skims through her article and finds error after error, including mistakes with the names of speakers. He pauses for a moment, after finding a third name that is incorrect, then angrily demands: “What, so you party all night and transcribe your tape sleepy and blurry eyed in the morning?” He gives her the accurate names and spellings and quickly says goodbye.

Dehbashi doesn’t always pick up his phone. If he purposely does not answer someone and they call back, he will have a word or two with them. He barks angrily at one caller who has phoned three times in less than two minutes: “Maybe I can’t pick up the phone right now, hasn’t anyone taught you to not keep calling?” Journalists phone him often, a group with which he sometimes has tense relations. “An arts journalist working for a prominent paper once called me to inform me of an event,” he says, “naming Virginia Woolf as one of the guests — that’s the state we are in.” While I am sitting there one day, a reporter from a local news agency, a young woman, calls him and asks him to double-check a story she is running about a reading he recently hosted. He skims through her article and finds error after error, including mistakes with the names of speakers. He pauses for a moment, after finding a third name that is incorrect, then angrily demands: “What, so you party all night and transcribe your tape sleepy and blurry eyed in the morning?” He gives her the accurate names and spellings and quickly says goodbye.

Dehbashi is divorced, with a son, Shahab, who is a documentary filmmaker. Dehbashi confesses that he “neglected” his son to work on Bukhara, but that Shahab is slowly coming around to realizing the value of what his father tried to build. He tells the story of barely making it to the hospital in time for Shahab’s birth, arriving with his video camera in hand just as he was born. “And only a few minutes before, I ran into the room, and pressed record.”

Dehbashi’s social circle consists of Persian literature’s aging poets and scholars, some to whom he’s attended like a son. Nasser-edin Sahebzamani, author of The Third Script, a seminal work on Rumi’s spiritual instructor, Shams-e Tabrizi, says Dehbashi takes care of the “cultural dinosaurs.” But that is the drive behind much of Dehbashi’s work: to care for and recognize the giants he sees before him, whether in Tehran, Hamedan, Dushanbe, or Samarkand.

“My father was the stern military type. He’d point to our mother and ask: khanom [madam], what grade is that one in?” Instead, he explains, he found attentive caregivers in the literary scholars Anjavi Shirazi and Abdolhossein Zarrinkoob — both of whom are now deceased. He says: “I have had to see my father die, many times.” Along with Shirazi and Zarrinkoob, Dehbashi speaks fondly of Simin Behbahani, a poetess whom he knew well and who passed away in 2014. He tells me: “Somewhere in the afterlife, Anjavi and Simin are sitting together drinking tea and talking and I’d love to join them,” he hesitates here, “but not before publishing the latest issue of Bukhara.”

While spanning a long career in the publishing business, beginning with a summer job as an assistant in a printing house at the age of 12, Dehbashi’s most prominent work has been the publication of KELK and Bukhara, both literary magazines. Dehbashi worked as editor-in-chief of KELK from 1990 until 1997 when owner Mirkasra Haj Seyed Javadi dismissed him. Issue 94 of KELK, the last on which Dehbashi worked, was a tribute to Fereydun Adamiyat — son of a prominent supporter of Iran’s 1906 Constitutional Revolution and a later historian of that revolution, who became a high-ranking deputy of the foreign ministry under the Shah. Adamiyat chose to stay in Tehran following the revolution of 1979, but lived the rest of his days in seclusion.

After his dismissal from KELK, Dehbashi began where he left off by publishing Bukhara magazine within less than a year. But painter Aydin Aghdashloo hints at what Dehbashi’s removal from KELK meant to him: “His life project, momentarily failed.” Dehbashi calls Bukhara, which has now run for 111 issues, and 18 years, the “logical continuum of KELK.” At more than 500 pages printed on inexpensive groundwood paper, each issue presents analyses, critiques, poems, and photography. The connecting theme of the publication is a general focus on Iranian studies, but Iran as defined by the “cultural borders of the Persian language,” Dehbashi stresses. The face of one prominent person is featured on every cover, about which a number of articles appear. In September 2015, the 107th issue honored archeologist Shahriar Adl who passed away suddenly in Paris, having led excavation projects in Iran for four decades. Translations of Adl’s academic papers were published, as well as eulogies written by family and friends such as historian Ehsan Eshraghi and Irina Bokova, director general of UNESCO, an organization with which Adl collaborated regularly.

As Moshiri had noted during his speech years ago, Ali Dehbashi is not only the editor-in-chief of Bukhara, but the advertising manager, photo editor, and print production manager — the latter of which severely damaged his health, aggravating his asthma after spending long hours by the printing press for each issue. “I once went home to sleep for a few hours during a night shift at the chapkhooneh (printing house) and came back to find the printers sleeping too, despite having promised to finish the work. I’ll never repeat that mistake.” Almost daily, he visits Tehran’s paper district located in historic Zahir Ol-Eslam Street to check the price of paper and make a purchase when he thinks it cheap enough. “Paper has to be stored for the magazine, we can’t afford to buy all we need at once at any price.” He can trust no one else with the job he claims — not with his discipline.

To ensure the continuity of Bukhara, there are 6,432 pages of the magazine ready for publication. They lie in neat boxes, edited, typed, and formatted. “I could die tomorrow and the magazine could continue for a few years,” Dehbashi says. He saves three copies of these pages: one at his mother’s home, one at a friend’s, and one in his apartment.

Each issue of Bukhara is printed in 8,500 copies. 300 are sent to writers and institutions in Tajikistan, Pakistan, and India. The rest are distributed to kiosks and stores in Tehran and major cities. Still, the magazine incurs a loss of about three million tomans ($900) per issue, Dehbashi tells me. He explains that he tries to cover the costs in other ways. “I’m currently printing tomato sauce labels for a food company,” he laughs. All of this points to the fact that Bukhara is not the hottest thing on the newsstand. “I was once turned away at an ad agency because the secretary could not read the name on our cover and we were not using glossy paper,” he says, in his signature tone which moves between the mocking and the tragic. The logo she failed to read was designed by famed Iranian calligrapher and painter Mohammad Ehsai, and features the word Bukhara in simple Nastaliq script.

Dehbashi summarizes the perils of his work this way: “If you want to get something done, if you want to have an impact, you have to be prepared to face an uphill battle. In this country specifically, you have to be ready to have your shirt buttons yanked off and bricks thrown at you — even if what you want to do is as simple as walking from here to Enqelab Square” — a 10 minute walk from his house. Dehbashi’s metaphors frequently invoke physical harm or lurking danger. His alarming tone dramatically shifts when he speaks of the Persian language, cites a poem, or recalls the tiles and domes of Shiraz, Bukhara, or Samarkand — with a twinkle in his eyes and a lighthearted voice. Something beyond material comfort and recognition drives him.

When I press him about his financial wellbeing, he does not give a clear answer, but chooses to launch into another story. Behesht-e Zahra, in south Tehran, is a massive cemetery, where more than one million bodies are currently buried and where a grave can cost anywhere from three million tomans in the newer sections with few trees, to 30 million tomans in the older sections that are filled with ample green spaces. The Artist’s Section of the cemetery is where some of Iran’s most noted contemporary artists and scholars are buried. Years ago, Dehbashi was gifted a deed to a grave in the Artist’s Section in both recognition and reimbursement for the help he’d given the administration. “Then, one day I got word that they had buried someone in that space, so I called them. They said it was a two story grave.” He shrugs it off as inconsequential, his large body moving back and forth in laughter: “In this world, I owned a cell phone and a grave, and the grave I have to share now.”

When I press him about his financial wellbeing, he does not give a clear answer, but chooses to launch into another story. Behesht-e Zahra, in south Tehran, is a massive cemetery, where more than one million bodies are currently buried and where a grave can cost anywhere from three million tomans in the newer sections with few trees, to 30 million tomans in the older sections that are filled with ample green spaces. The Artist’s Section of the cemetery is where some of Iran’s most noted contemporary artists and scholars are buried. Years ago, Dehbashi was gifted a deed to a grave in the Artist’s Section in both recognition and reimbursement for the help he’d given the administration. “Then, one day I got word that they had buried someone in that space, so I called them. They said it was a two story grave.” He shrugs it off as inconsequential, his large body moving back and forth in laughter: “In this world, I owned a cell phone and a grave, and the grave I have to share now.”

I ask him if out of the hundreds of literature students admitted to Tehran’s universities, he’s ever hired interns or assistants. “I get regular calls. Two weeks ago a student’s parents called and asked me to accept him as an assistant, so he could begin to learn about publishing and editing.” On the first few days, the student showed up late. The subsequent week, he forgot an appointment. And that was the end. Dehbashi works alone not only because there is no one — but no one that is as uncompromising. He recalls his conversation with Neysari to emphasize this point: “The media called Neysari’s talk with Kadkani and Sayeh, the epic day of Iranian literature, but the boy (a volunteer) filming it fell asleep during Kadkani’s talk.”

It matters not that Kadkani’s contributions may no longer be as interesting to a 25-year-old Iranian youth — one must respect an ostad (master’s) weight.

When I meet Dehbashi in February 2016, his health has deteriorated. He is in panic mode because his rent contract is about to expire with no renewal. In a daze, he wonders how he will move thousands of books, manuscripts, and photos that have not yet been archived. He also has help staying at his home for the first time. Mr. Razi is from the olive orchards of Rudbar, Gilan Province, north Iran. He says that he once saw Dehbashi interviewed on satellite television, and wondered about meeting him in person. He later moved to Tehran to work at a fast food restaurant, and bumped into Dehbashi one morning near the editor’s home. Razi writes song lyrics and says that he hopes to have singers like Ebi or Dariush, Iranian pop singers based in Los Angeles, sing them one day. He points to a pile of books Dehbashi has given him to read at night, helping him through the study of Persian literature. “I don’t know how long he’ll stay though,” Dehbashi later comments, “no one can take my temper after a while.”

This particular morning, Dehbashi is angry at a celebrated Iranian poet for traveling to Isfahan while having agreed to meet with a group of Afghan poets that were in Tehran by Dehbashi’s invitation. Dehbashi took this as the poet’s lack of respect for Afghanistan and is retelling the story to someone on the phone. At one point, his forehead bulging, he snaps: “This country does not need people who think they are masters, it needs decent human beings.” The poets from Afghanistan were in Tehran to read at a Bukhara event titled “Night of Afghan Poets.”

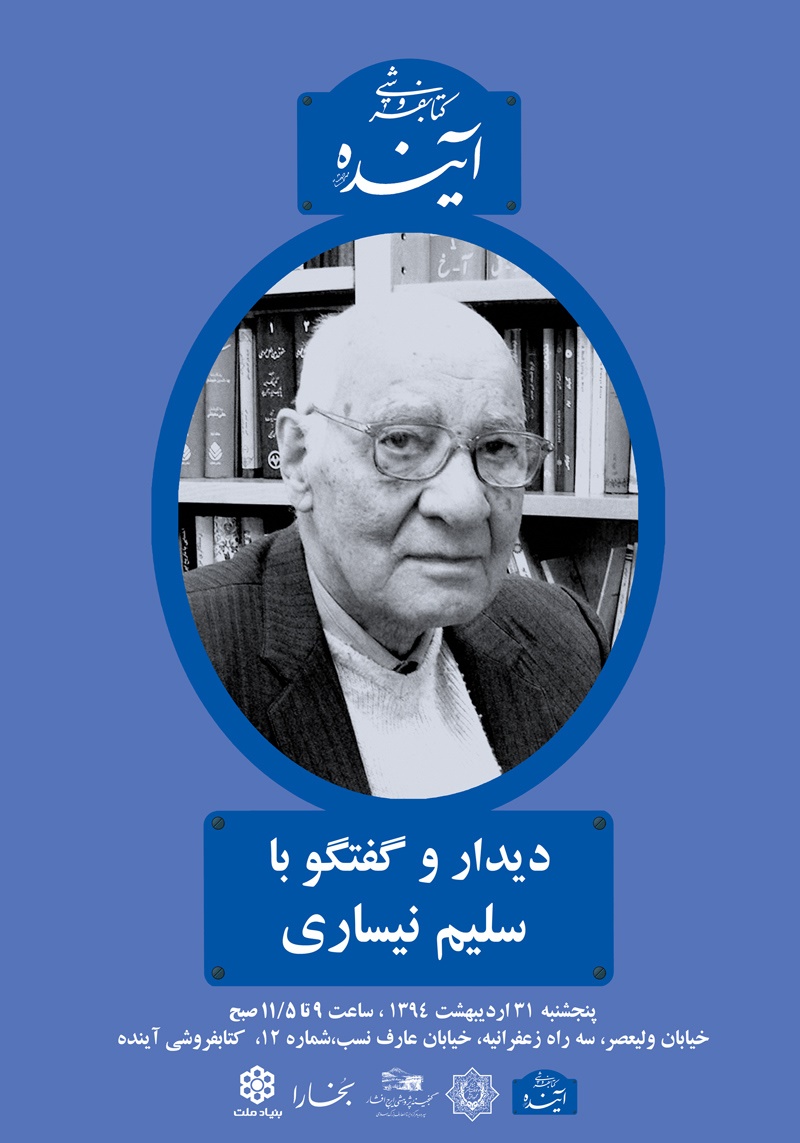

Under the Bukhara name, Dehbashi organizes and hosts a number of events. There is “Thursdays at Ayandeh Bookstore” — where Neysari appeared — a two-hour conversation between Dehbashi and a noted writer, artist, painter, or scholar. Canadian scholar Richard Foltz, French/Iranian translator Leili Anvar, Turkish Mowlavi scholar Adnan Oghloo, actress Fatemeh Motamed-Arya, and children’s novelist Houshang Moradi Kermani have been among the guests. He invites people he’d like to sit with and speak to, and tells me of his criteria: “They must be nationalist, independent, and have no affiliations with censorship.”

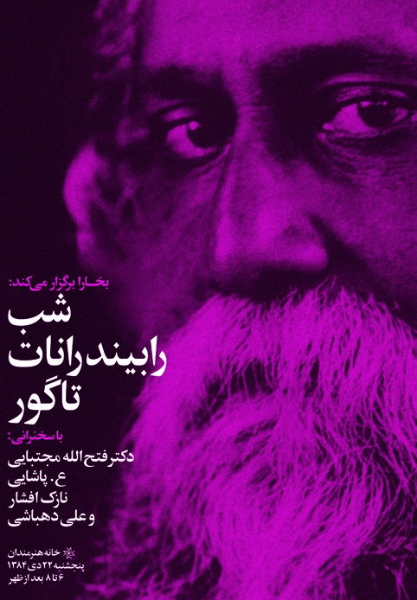

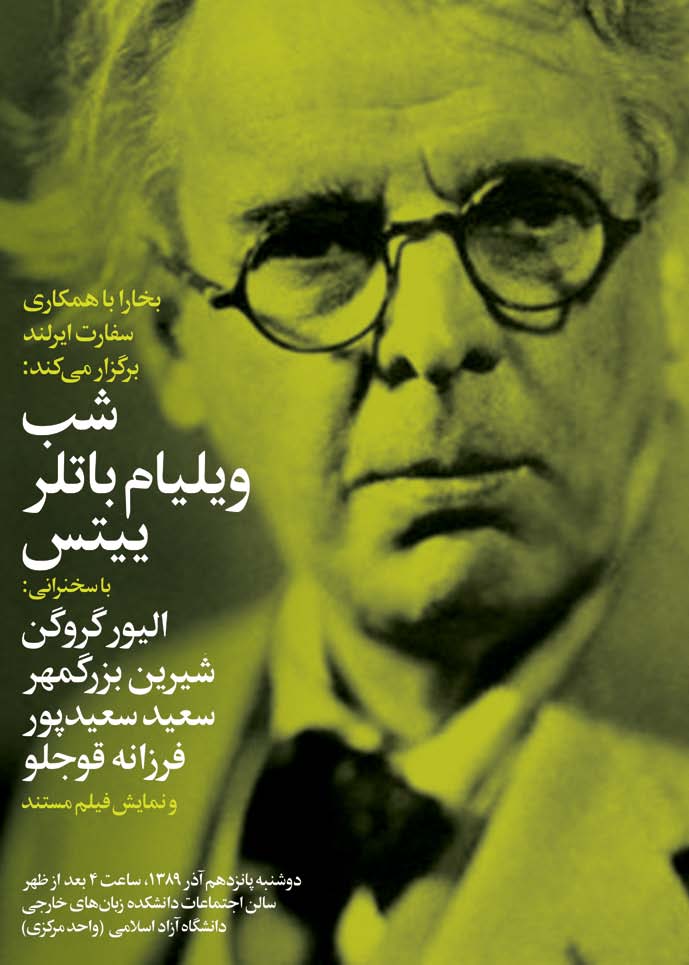

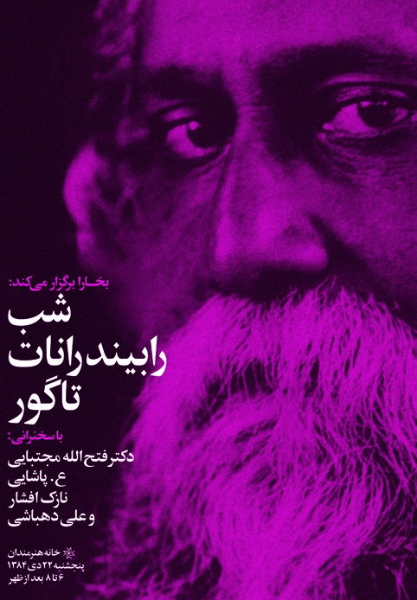

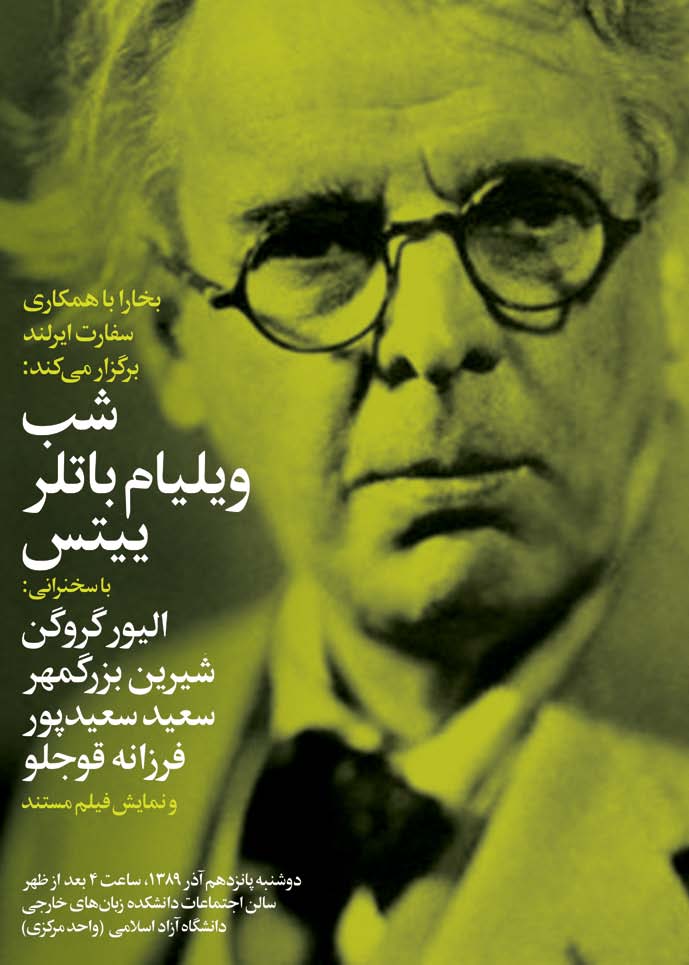

“Shabhayeh Bukhara” (“Bukhara Nights”) are held to commemorate writers, cities, artists, and histories. The first “Bukhara Night” in January 2006 honored Rabindranath Tagore — a favorite poet of Dehbashi’s late father. Since, “Bukhara Nights” have been held to honor Umberto Eco, Mahmoud Darwish, William Butler Yeats, the Polish essayist and poet Adam Mickiewicz, Hannah Arendt, Virginia Woolf, the Urdo poet Iftikhar Arif, and more. Some nights are organized around a theme: old Tehran; the art and poetry surrounding pomegranates; ancient Zoroastrian manuscripts; the Armenian Genocide; or Assyrian Literature.

Attendance is free and open to all. The auditorium where Dehbashi currently hosts “Bukhara Nights” has 110 seats, with an additional room that fits 50 chairs in front of a large screen display. If the guests are well known (a number of times Sayeh has agreed to attend) there will be people sitting on the floors and on the steps. There are no notices given for the event aside from an announcement on social media a day or two before. The Nights feature a combination of short lectures, musical performances, poetry readings, and documentary screenings — all that Dehbashi thinks will honor the topic fully.

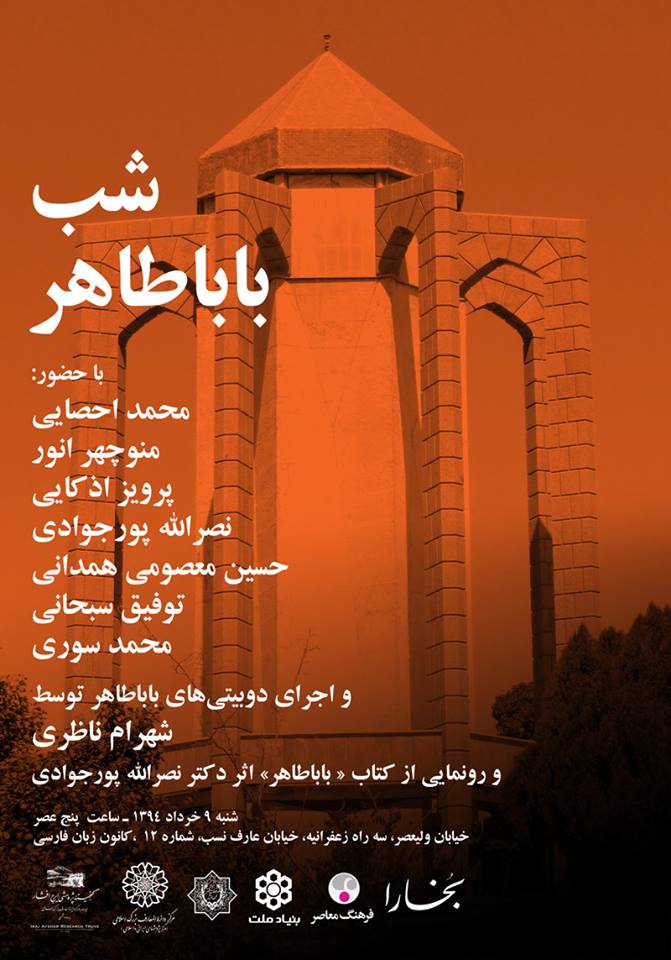

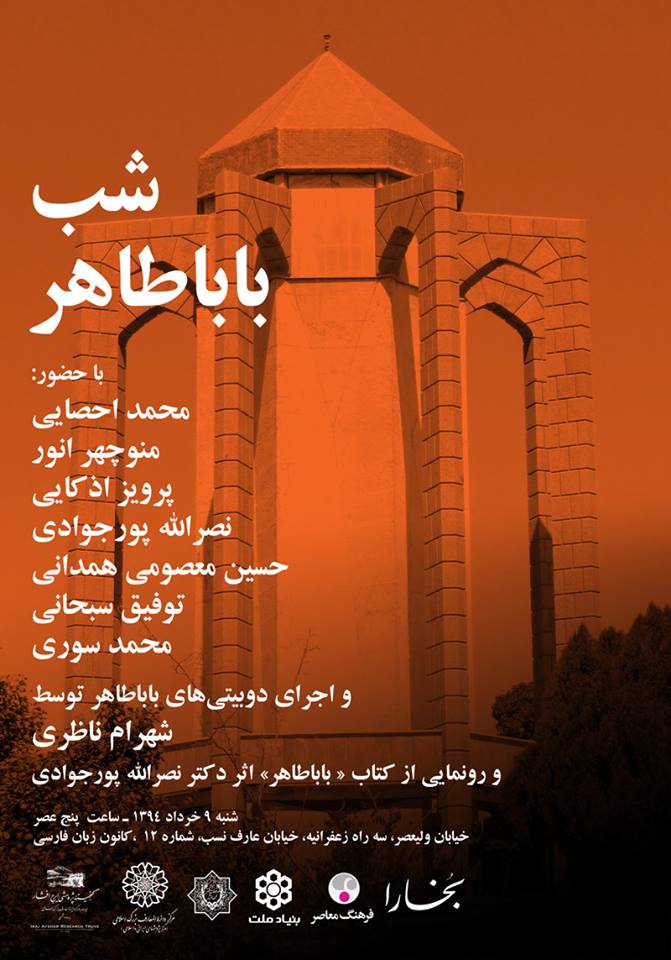

“Bukhara Nights” have slowly gathered critical acclaim, to become some of the city’s most significant cultural gatherings. The Night of Baba Tahir, the 11th-century Persian poet from Hamedan, was organized as a book and lecture for Nasrollah Pourjavadi’s new biography of Baba Tahir. It was also an opportunity for the 200 people in the audience to hear Mohammad Souri. Wearing his usual cap and worn shoes, Souri described his in-depth research into the Hamedan School of mysticism from Baba Tahir to Eyn ol Ghozat. Nowhere else in Tehran would Souri find a public audience for a topic that is both so fundamental to Iran’s understanding of its own intellectual history yet so stubbornly ignored. Vocalist Shahram Nazeri poignantly sang a number of Baba Tahir’s quatrains at the end.

“Bukhara Nights” have slowly gathered critical acclaim, to become some of the city’s most significant cultural gatherings. The Night of Baba Tahir, the 11th-century Persian poet from Hamedan, was organized as a book and lecture for Nasrollah Pourjavadi’s new biography of Baba Tahir. It was also an opportunity for the 200 people in the audience to hear Mohammad Souri. Wearing his usual cap and worn shoes, Souri described his in-depth research into the Hamedan School of mysticism from Baba Tahir to Eyn ol Ghozat. Nowhere else in Tehran would Souri find a public audience for a topic that is both so fundamental to Iran’s understanding of its own intellectual history yet so stubbornly ignored. Vocalist Shahram Nazeri poignantly sang a number of Baba Tahir’s quatrains at the end.

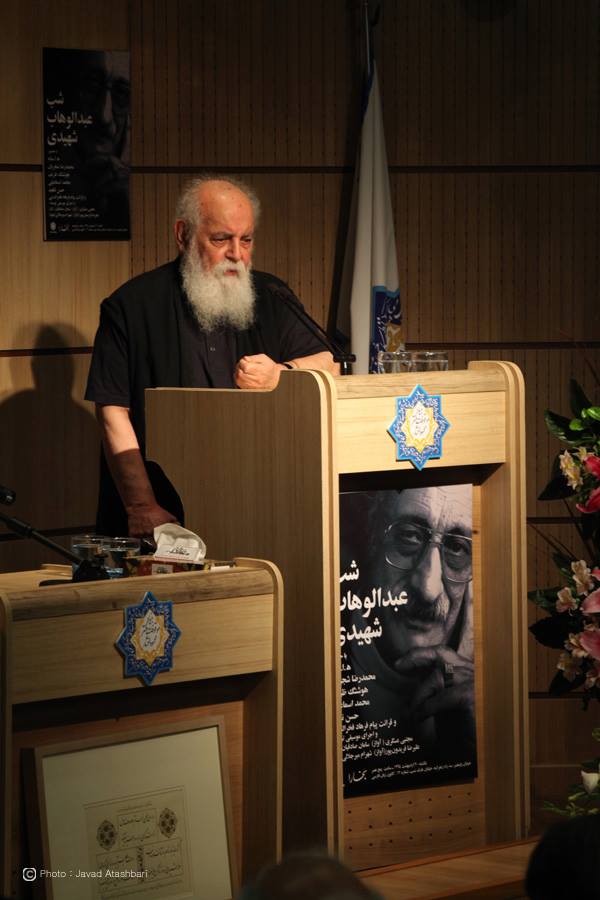

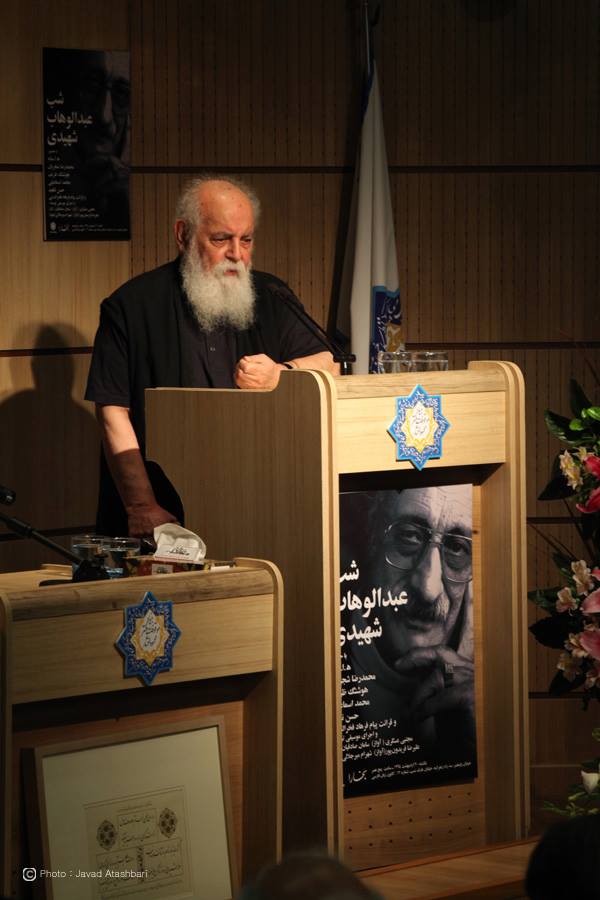

Other aims of Bukhara, one especially at the heart of Dehbashi’s work, is to honor those who have spent a lifetime on a particular branch of scholarship or the arts in Iran. On the night of legendary vocalist and oud player Abdul Wahhab Shahdi, one of the most widely attended to date, Sayeh came and cried during a speech recalling the hardships his friend had had to endure. Also present were Mohammad-Reza Shajarian, Iran’s most celebrated living classical lyricist, tar player Houshang Zarif and ney master Hassan Nahid. All knew Shahidi closely and spoke fondly of their time working with him. Dehbashi had spent well over a year trying to bring all five men in one room before Shahidi. “Bukhara Nights” link past and present, honor all that was and all that was lost, and link a new generation to the intricacies of what was before them.

Dehbashi is seen foremost for his work in literature and the arts within the Persian speaking cultural realm, “beyond the political” as he routinely reminds. But where exactly does the literary end and the political begin? Some of Iran’s most notable 20th-century poets were exiles or prisoners. Somewhere in the calling of the writer or intellectual is the negation of reality as promoted by the state. Dehbashi can never be far from the censorship apparatus.

He is now in court for the second time, over the publication of a poem in Bukhara that authorities deemed disrespectful to women with chador. This bears heavily on him — a ruling might close down the magazine. Dehbashi’s gatherings too are continuously under scrutiny. Often the guests speak on a whim, on a whole range of topics, both socially or politically taboo.

“Bukhara Nights” was launched in 2006. Weekly conversations with writers began as Thursday Afternoons at Bukhara in 2008. Among his early guests were the vocalist Pari Zangeneh, cultural theorist and scholar Dariush Shayegan, Tudeh activist turned critic and writer Anvar Khamei. Afternoon events, which Dehbashi hosted at his office, were brought to a standstill when the hardline newspaper Kayhan published a story titled, “Thursday evenings with the Freemasonry.” He subsequently organized Tuesday Mornings at Nashr-e Sales at the café on the upper floor of Sales Bookstore. He had to stop those meetings when the manager of Sales was called and told not to let Dehbashi in. Then, came the Afshar Foundation.

Mahmoud Afshar and his son, Iraj, with which Dehbashi was particularly close, were prolific scholars of the Persian language. They were also descendants of wealthy merchants of Yazd. In north Tehran’s upscale Valiasr Avenue, home to Iran’s highest priced real estate, lies Mowqoofat-e Mahmoud Afshar, the religious endowments that Mahmoud left for the publication, presentation, and propagation of scholarly and literary works of the Persian language. The home that Mahmoud Afshar and his wife shared has since been turned into an auditorium. The endowment saved the house from becoming a high rise. Dehbashi has been able to use that space to host “Bukhara Nights” and weekly conversations. The head of the Mowqoofat is cleric Ayatollah Mohaghegh Damad, academic and researcher, involved with both university and research institutions like the Center for the Great Islamic Encyclopedia established in 1984. Mohaghegh Damad is one of the only clerics to regularly appear at Bukhara.

Dehbashi, as anyone else closely involved with independent publishing, is also on the forefront of political disruptions. He has, often miraculously, been able to carry forward from the presidency of reformist President Khatami through the very tumultuous Ahmadinejad years when government played a much more prominent role in censorship. Mohammad-Ali Ramin became the Press Deputy at the Ministry of Culture under Ahmadinejad, tasked with leading an unprecedented shutdown of newspapers and magazines, while Ahmad Bourghani held that post in the Khatami administration. The media and publishing community, including Dehbashi, remember Bourghani fondly. “He took my side when Kayhan called me a freemason. Told them that what they really wanted to do was shut me down with baseless accusations.”

Underlying much of Dehbashi’s work at Bukhara lingers an uneasy feeling that the Persian language in Iran no longer has such committed custodians as it once did. Most specifically, university and publishing institutions, who in tandem gave rise to the best literary productions of the 20th century, do not produce writers and scholars of national and international stature as they once did. Shafiei Kadkani is the last of University of Tehran’s famed literature professors, a department where scholars like Badiozzaman Forouzanfar and Abdolhossein Zarrinkoob once taught. Literary magazines like Bukhara are not as prominent as they once were. Kadkani and Ebtehaj belong to the “golden age” of contemporary Iranian poetry and scholarship, which often feels like a bygone era.

Can the nascent literary enthusiasts of today be connected to the generations before them? Dehbashi’s events, each in their own way, attempt to bridge the old with the new. He has been walking the streets of Tehran for decades now, organizing, hosting, editing, and publishing, despite the buttons that have been yanked off. One wonders how long the shirt, and the man wearing it, will hold.

Pedestrian is a writer from Khuzestan, in southern Iran. Across and over clashing, intersecting, and merging borders, she now lives between Iran and the US.

IT’S 9 A.M. on a cool but sunny Tehran morning in the spring. We sit in a corner of a garden in Bagh-e Ferdows, upper Valiasr Street, one of the only few homes of the early Pahlavi era that have not yet been razed to make way for an apartment building, or a high rise. There are sycamore trees all around us, once ubiquitous in the vast orchards that ran through this area. Every now and then two of the cats that frequent the garden casually pass by, their tails curved in the air. Ali Dehbashi, editor of Tehran’s Bukhara magazine, begins his conversation with scholar Salim Neysari, facing an audience of about 60, sitting on stone steps made into an open-air auditorium. Water, tea, coffee, and an assortment of pastries are offered in a corner.

Salim Neysari is 95 years old. His career spans 70 years as an administrator, dean, writer, researcher, and academic. He is also a keen reader of every existing manuscript of Divan-e Hafez, which total 48, and can effortlessly run through verses that differ from manuscript to manuscript. Nearly 500 ghazals make up the Divan of Hafez, all composed by the 14th-century poet who is perhaps the most widely read throughout the Persian speaking world. Verses in a number of his ghazals are common proverbs or sayings in the Persian language, including the first verse of the opening poem: “Keh eshgh asan nemood aval vali oftad moshkelha” — “Many hardships await on the path of love, that at first glance, showed to be simple.”

As Neysari begins to speak, the sound of a cane alerts the audience to a new presence. Even from the corner of our eyes we can spot that signature beard, flowing like a waterfall. The poet Houshang Ebtehaj, whose pen name is Sayeh, walks in with small, hesitant strides. Starstruck and giddy, we all want to look his way, but that would be disrespectful to the speaker. Neysari himself solves the dilemma, looking toward Sayeh and welcoming him warmly, while Dehbashi asks one of the volunteers to take him a chair. Days before the event on a social media, some speculate that Sayeh might be here today given his friendship with Neysari. But he rarely makes public appearances, so members remained undecided.

Ebtehaj is Iran’s most celebrated living poet. For 60 years, he has been both political activist and prisoner, involved with the leftist literary movement, revolution, and exile. In the early 1950s, along with poets Morteza Keyvan and Siavash Kasrai, he formed a social, political poetry circle that became both celebrated and widely read. Keyvan played a central role in connecting young leftist poets and intellectuals of his day. Sayeh, Kasrai, Mehdi Akhavan-Sales, and Ahmad Shamloo, among others, found their beginnings in his literary gatherings and vividly recall his cultural influence. Keyvan was the only civilian executed following the 1953 coup which ousted Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh. He was 33 years old. Sayeh writes of Keyvan’s unmarked grave: “Oh dear of my heart, which sycamore are you?”

Ebtehaj is Iran’s most celebrated living poet. For 60 years, he has been both political activist and prisoner, involved with the leftist literary movement, revolution, and exile. In the early 1950s, along with poets Morteza Keyvan and Siavash Kasrai, he formed a social, political poetry circle that became both celebrated and widely read. Keyvan played a central role in connecting young leftist poets and intellectuals of his day. Sayeh, Kasrai, Mehdi Akhavan-Sales, and Ahmad Shamloo, among others, found their beginnings in his literary gatherings and vividly recall his cultural influence. Keyvan was the only civilian executed following the 1953 coup which ousted Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh. He was 33 years old. Sayeh writes of Keyvan’s unmarked grave: “Oh dear of my heart, which sycamore are you?” More than any other contemporary poet, Sayeh is referred to as the “Hafez of the age.” In 1967, at the Shiraz Arts Festival, he was scheduled to read his ghazals to an anticipating crowd waiting at the Mausoleum of Hafez. Travel writer and historian Mohammad Ebrahim Bastani Parizi later recalled that he had never before “seen audiences so welcoming and receptive to new poetry.” Neysari points to him when he is asked who he believes to be Iran’s greatest living poet. But this is far from a settled argument. Editor Manuchehr Anvar once commented during his own talk weeks before: “Persian literature stopped producing giants like Hafez long ago. We must now talk amongst ourselves in the world of dwarves.”

More than any other contemporary poet, Sayeh is referred to as the “Hafez of the age.” In 1967, at the Shiraz Arts Festival, he was scheduled to read his ghazals to an anticipating crowd waiting at the Mausoleum of Hafez. Travel writer and historian Mohammad Ebrahim Bastani Parizi later recalled that he had never before “seen audiences so welcoming and receptive to new poetry.” Neysari points to him when he is asked who he believes to be Iran’s greatest living poet. But this is far from a settled argument. Editor Manuchehr Anvar once commented during his own talk weeks before: “Persian literature stopped producing giants like Hafez long ago. We must now talk amongst ourselves in the world of dwarves.”Walking in with Sayeh and later sitting to his right is Mohammad-Reza Shafiei Kadkani, a poet and one of University of Tehran’s most distinguished professors, and a scholar of medieval Persian Sufi manuscripts. Students from all across the country travel to the capital to attend his classes at the University of Tehran. During lectures, they sit on the floors, by the doorway, and on the window sill, often leaving him no place to go other than his desk (his chair is first to be given out to one of the standing students). His revision to more than 20,000 verses of mystical narrative poetry by the 12th-century Sufi poet Farid ud-Din Attar of Nishapur was published in recent years to wide critical acclaim. The multi-volume project includes a thousand pages of commentary in addition to the poems. Kadkani meticulously traces the sources of Attar’s poems to earlier books, stories, and mystics, and describes the roots and meanings of Sufi expressions, making Attar’s words accessible to a new generation. Rumi, who is more widely known and read in Iran and the West, writes: “Attar has traversed the seven cities of love, while we are only on the first street.”

The most accomplished of Iran’s students go to schools of engineering or medicine today. Kadkani was educated during an era where his overachievement (he could recite Ibn Malik’s 13th-century book of Arabic grammar by heart at the age of eight) led him to poetry and literature. He holds a stature of unparalleled admiration from the public, so much so that when he left Iran for Princeton in 2009 following the contested elections in June of that year, it was the gravest sign of what Iran had become: even Shafiei Kadkani would leave now. Rumors circulated that he would never return. And perhaps, that he did return a year later, was also a sign of how that Iran carries forward.

Salim Neysari has never before granted an interview, nor has he given a public talk. Kadkani and Sayeh are not seen at Tehran’s increasing number of book readings and cultural circles. Only one man can bring together artists, scholars, and writers of this caliber: Ali Dehbashi. Here, he is in his element, his lips curve in a smile of satisfaction; his usually worried eyes are calm. He has spent a lifetime cultivating relationships that would make this day possible — both for speakers and audience. Since his career began as an editor in the 1970s, Dehbashi has cemented his place as “the lover of the Persian language, across political borders,” as he is called by many who know him. He has also provided a gathering space for the artists of this language, and its legacy, to be presented and explored. In tandem with such efforts, he publishes what remains Iran’s most influential literary magazine: Bukhara.

The late Fereydoon Moshiri, whose poetry President Obama cited in his 2016 Nowruz message, was one of Iran’s most beloved writers. In 2000, just months before he died, he spoke at a ceremony marking the third year of Bukhara’s publication. He described how Ali Dehbashi singlehandedly publishes the magazine, nafas nafas zanan, always short of breath due to the severe asthma that Moshiri has seen “from up close.” “His right shoulder is always bent due to the weight of the bag he carries,” Moshiri continues, while pushing his right shoulder down with his left hand to show how Dehbashi stands with his signature shoulder bag, his “office, archive, library, and editing desk.” Like most other people who mention Dehbashi, he reminds the audience of the price the editor pays to bring each issue of the magazine to publication, one that he always anticipates: “I sit there, asking whoever walks in if it is in the mail.”

¤

Ali Dehbashi rents a house on the first floor of a four-story apartment building — which currently serves as both his residence and the Bukhara office in downtown Tehran. The front door is open during visiting hours, early mornings, when I drop by every now and then. A hallway leads to a yard where dozens of tiny pots of flowers, either on the ground or on wooden stools are aligned in neat rows. He attends to the plants daily before heading out of the house. At the end of the yard, on the right, there is a door leading to the unit which serves as his home and office.

Inside, staring eyes confront the visitor in every direction: wide-eyed owl figurines made of sea shells, wood, ceramic, clay, metal, and straw. They hang from shelves and cases, or hold on to dear life from the outer most edge of a table — what can be seen of a table that is, upon which lie hundreds of pages of paper, books, and manuscripts. Long wooden bookshelves cover the walls from floor to ceiling in the living room. On the upper shelf of every case, fine leather-bound issues of magazines Dehbashi has edited, including Bukhara, shine with gold and green calligraphy. In front of each bookcase, a collection of folders, boxes, and more books are scattered. I spot a portable oxygen tank and inhalers in between the piles, hinting at how this chaotic calm can be instantaneously shattered. Photos of Dehbashi and writers and poets hang in various corners of the living room. One shows a much younger (and much thinner) Dehbashi gleefully smiling at the late Akhavan-Sales. He tells me that he has an archive of thousands of these photos in storage.

Copies of the French literary magazine Le Magazine Littéraire, a book of photos of Ernest Hemingway, and The Ultimate Book of Pens (Dehbashi collects fine pens) are among the other publications casually thrown around. Dehbashi knows exactly where everything is, and can effortlessly reach out and take a sheet of paper lying unseen beneath the stacks. Among the piles, visitors can find a stool or a chair or just an empty place to sit. Dehbashi warns guests about making a mess.

During the cold season, a thin camel-colored wool blanket hangs from Dehbashi’s shoulder as he moves from one part of the room to the other while receiving company, mail, editing or proofreading articles, and responding to phone calls on his cell. He does not use headsets on his phone, but instead chooses to put the phone on speaker and hold it horizontally in his right hand.

A student calls to say that he has gotten Dehbashi’s number through a professor, and needs help with a thesis on “how modernity is represented in Persian novels.” Dehbashi questions the student to get more details, in the process also quickly assessing the student’s knowledge and interest. He ends the conversation when he concludes that that the caller does not have much to offer, instead wanting Dehbashi to do his homework. He looks at his phone with disgust after hanging up. “This new generation is shallow in every aspect. I ask for details and he says he has to hand in the thesis in three months and, ‘oh I want to know about story writing in general.’”

Dehbashi doesn’t always pick up his phone. If he purposely does not answer someone and they call back, he will have a word or two with them. He barks angrily at one caller who has phoned three times in less than two minutes: “Maybe I can’t pick up the phone right now, hasn’t anyone taught you to not keep calling?” Journalists phone him often, a group with which he sometimes has tense relations. “An arts journalist working for a prominent paper once called me to inform me of an event,” he says, “naming Virginia Woolf as one of the guests — that’s the state we are in.” While I am sitting there one day, a reporter from a local news agency, a young woman, calls him and asks him to double-check a story she is running about a reading he recently hosted. He skims through her article and finds error after error, including mistakes with the names of speakers. He pauses for a moment, after finding a third name that is incorrect, then angrily demands: “What, so you party all night and transcribe your tape sleepy and blurry eyed in the morning?” He gives her the accurate names and spellings and quickly says goodbye.

Dehbashi doesn’t always pick up his phone. If he purposely does not answer someone and they call back, he will have a word or two with them. He barks angrily at one caller who has phoned three times in less than two minutes: “Maybe I can’t pick up the phone right now, hasn’t anyone taught you to not keep calling?” Journalists phone him often, a group with which he sometimes has tense relations. “An arts journalist working for a prominent paper once called me to inform me of an event,” he says, “naming Virginia Woolf as one of the guests — that’s the state we are in.” While I am sitting there one day, a reporter from a local news agency, a young woman, calls him and asks him to double-check a story she is running about a reading he recently hosted. He skims through her article and finds error after error, including mistakes with the names of speakers. He pauses for a moment, after finding a third name that is incorrect, then angrily demands: “What, so you party all night and transcribe your tape sleepy and blurry eyed in the morning?” He gives her the accurate names and spellings and quickly says goodbye.Dehbashi is divorced, with a son, Shahab, who is a documentary filmmaker. Dehbashi confesses that he “neglected” his son to work on Bukhara, but that Shahab is slowly coming around to realizing the value of what his father tried to build. He tells the story of barely making it to the hospital in time for Shahab’s birth, arriving with his video camera in hand just as he was born. “And only a few minutes before, I ran into the room, and pressed record.”

Dehbashi’s social circle consists of Persian literature’s aging poets and scholars, some to whom he’s attended like a son. Nasser-edin Sahebzamani, author of The Third Script, a seminal work on Rumi’s spiritual instructor, Shams-e Tabrizi, says Dehbashi takes care of the “cultural dinosaurs.” But that is the drive behind much of Dehbashi’s work: to care for and recognize the giants he sees before him, whether in Tehran, Hamedan, Dushanbe, or Samarkand.

“My father was the stern military type. He’d point to our mother and ask: khanom [madam], what grade is that one in?” Instead, he explains, he found attentive caregivers in the literary scholars Anjavi Shirazi and Abdolhossein Zarrinkoob — both of whom are now deceased. He says: “I have had to see my father die, many times.” Along with Shirazi and Zarrinkoob, Dehbashi speaks fondly of Simin Behbahani, a poetess whom he knew well and who passed away in 2014. He tells me: “Somewhere in the afterlife, Anjavi and Simin are sitting together drinking tea and talking and I’d love to join them,” he hesitates here, “but not before publishing the latest issue of Bukhara.”

While spanning a long career in the publishing business, beginning with a summer job as an assistant in a printing house at the age of 12, Dehbashi’s most prominent work has been the publication of KELK and Bukhara, both literary magazines. Dehbashi worked as editor-in-chief of KELK from 1990 until 1997 when owner Mirkasra Haj Seyed Javadi dismissed him. Issue 94 of KELK, the last on which Dehbashi worked, was a tribute to Fereydun Adamiyat — son of a prominent supporter of Iran’s 1906 Constitutional Revolution and a later historian of that revolution, who became a high-ranking deputy of the foreign ministry under the Shah. Adamiyat chose to stay in Tehran following the revolution of 1979, but lived the rest of his days in seclusion.

After his dismissal from KELK, Dehbashi began where he left off by publishing Bukhara magazine within less than a year. But painter Aydin Aghdashloo hints at what Dehbashi’s removal from KELK meant to him: “His life project, momentarily failed.” Dehbashi calls Bukhara, which has now run for 111 issues, and 18 years, the “logical continuum of KELK.” At more than 500 pages printed on inexpensive groundwood paper, each issue presents analyses, critiques, poems, and photography. The connecting theme of the publication is a general focus on Iranian studies, but Iran as defined by the “cultural borders of the Persian language,” Dehbashi stresses. The face of one prominent person is featured on every cover, about which a number of articles appear. In September 2015, the 107th issue honored archeologist Shahriar Adl who passed away suddenly in Paris, having led excavation projects in Iran for four decades. Translations of Adl’s academic papers were published, as well as eulogies written by family and friends such as historian Ehsan Eshraghi and Irina Bokova, director general of UNESCO, an organization with which Adl collaborated regularly.

As Moshiri had noted during his speech years ago, Ali Dehbashi is not only the editor-in-chief of Bukhara, but the advertising manager, photo editor, and print production manager — the latter of which severely damaged his health, aggravating his asthma after spending long hours by the printing press for each issue. “I once went home to sleep for a few hours during a night shift at the chapkhooneh (printing house) and came back to find the printers sleeping too, despite having promised to finish the work. I’ll never repeat that mistake.” Almost daily, he visits Tehran’s paper district located in historic Zahir Ol-Eslam Street to check the price of paper and make a purchase when he thinks it cheap enough. “Paper has to be stored for the magazine, we can’t afford to buy all we need at once at any price.” He can trust no one else with the job he claims — not with his discipline.

To ensure the continuity of Bukhara, there are 6,432 pages of the magazine ready for publication. They lie in neat boxes, edited, typed, and formatted. “I could die tomorrow and the magazine could continue for a few years,” Dehbashi says. He saves three copies of these pages: one at his mother’s home, one at a friend’s, and one in his apartment.

Each issue of Bukhara is printed in 8,500 copies. 300 are sent to writers and institutions in Tajikistan, Pakistan, and India. The rest are distributed to kiosks and stores in Tehran and major cities. Still, the magazine incurs a loss of about three million tomans ($900) per issue, Dehbashi tells me. He explains that he tries to cover the costs in other ways. “I’m currently printing tomato sauce labels for a food company,” he laughs. All of this points to the fact that Bukhara is not the hottest thing on the newsstand. “I was once turned away at an ad agency because the secretary could not read the name on our cover and we were not using glossy paper,” he says, in his signature tone which moves between the mocking and the tragic. The logo she failed to read was designed by famed Iranian calligrapher and painter Mohammad Ehsai, and features the word Bukhara in simple Nastaliq script.

Dehbashi summarizes the perils of his work this way: “If you want to get something done, if you want to have an impact, you have to be prepared to face an uphill battle. In this country specifically, you have to be ready to have your shirt buttons yanked off and bricks thrown at you — even if what you want to do is as simple as walking from here to Enqelab Square” — a 10 minute walk from his house. Dehbashi’s metaphors frequently invoke physical harm or lurking danger. His alarming tone dramatically shifts when he speaks of the Persian language, cites a poem, or recalls the tiles and domes of Shiraz, Bukhara, or Samarkand — with a twinkle in his eyes and a lighthearted voice. Something beyond material comfort and recognition drives him.

When I press him about his financial wellbeing, he does not give a clear answer, but chooses to launch into another story. Behesht-e Zahra, in south Tehran, is a massive cemetery, where more than one million bodies are currently buried and where a grave can cost anywhere from three million tomans in the newer sections with few trees, to 30 million tomans in the older sections that are filled with ample green spaces. The Artist’s Section of the cemetery is where some of Iran’s most noted contemporary artists and scholars are buried. Years ago, Dehbashi was gifted a deed to a grave in the Artist’s Section in both recognition and reimbursement for the help he’d given the administration. “Then, one day I got word that they had buried someone in that space, so I called them. They said it was a two story grave.” He shrugs it off as inconsequential, his large body moving back and forth in laughter: “In this world, I owned a cell phone and a grave, and the grave I have to share now.”

When I press him about his financial wellbeing, he does not give a clear answer, but chooses to launch into another story. Behesht-e Zahra, in south Tehran, is a massive cemetery, where more than one million bodies are currently buried and where a grave can cost anywhere from three million tomans in the newer sections with few trees, to 30 million tomans in the older sections that are filled with ample green spaces. The Artist’s Section of the cemetery is where some of Iran’s most noted contemporary artists and scholars are buried. Years ago, Dehbashi was gifted a deed to a grave in the Artist’s Section in both recognition and reimbursement for the help he’d given the administration. “Then, one day I got word that they had buried someone in that space, so I called them. They said it was a two story grave.” He shrugs it off as inconsequential, his large body moving back and forth in laughter: “In this world, I owned a cell phone and a grave, and the grave I have to share now.”I ask him if out of the hundreds of literature students admitted to Tehran’s universities, he’s ever hired interns or assistants. “I get regular calls. Two weeks ago a student’s parents called and asked me to accept him as an assistant, so he could begin to learn about publishing and editing.” On the first few days, the student showed up late. The subsequent week, he forgot an appointment. And that was the end. Dehbashi works alone not only because there is no one — but no one that is as uncompromising. He recalls his conversation with Neysari to emphasize this point: “The media called Neysari’s talk with Kadkani and Sayeh, the epic day of Iranian literature, but the boy (a volunteer) filming it fell asleep during Kadkani’s talk.”

It matters not that Kadkani’s contributions may no longer be as interesting to a 25-year-old Iranian youth — one must respect an ostad (master’s) weight.

¤

When I meet Dehbashi in February 2016, his health has deteriorated. He is in panic mode because his rent contract is about to expire with no renewal. In a daze, he wonders how he will move thousands of books, manuscripts, and photos that have not yet been archived. He also has help staying at his home for the first time. Mr. Razi is from the olive orchards of Rudbar, Gilan Province, north Iran. He says that he once saw Dehbashi interviewed on satellite television, and wondered about meeting him in person. He later moved to Tehran to work at a fast food restaurant, and bumped into Dehbashi one morning near the editor’s home. Razi writes song lyrics and says that he hopes to have singers like Ebi or Dariush, Iranian pop singers based in Los Angeles, sing them one day. He points to a pile of books Dehbashi has given him to read at night, helping him through the study of Persian literature. “I don’t know how long he’ll stay though,” Dehbashi later comments, “no one can take my temper after a while.”

This particular morning, Dehbashi is angry at a celebrated Iranian poet for traveling to Isfahan while having agreed to meet with a group of Afghan poets that were in Tehran by Dehbashi’s invitation. Dehbashi took this as the poet’s lack of respect for Afghanistan and is retelling the story to someone on the phone. At one point, his forehead bulging, he snaps: “This country does not need people who think they are masters, it needs decent human beings.” The poets from Afghanistan were in Tehran to read at a Bukhara event titled “Night of Afghan Poets.”

Under the Bukhara name, Dehbashi organizes and hosts a number of events. There is “Thursdays at Ayandeh Bookstore” — where Neysari appeared — a two-hour conversation between Dehbashi and a noted writer, artist, painter, or scholar. Canadian scholar Richard Foltz, French/Iranian translator Leili Anvar, Turkish Mowlavi scholar Adnan Oghloo, actress Fatemeh Motamed-Arya, and children’s novelist Houshang Moradi Kermani have been among the guests. He invites people he’d like to sit with and speak to, and tells me of his criteria: “They must be nationalist, independent, and have no affiliations with censorship.”

“Shabhayeh Bukhara” (“Bukhara Nights”) are held to commemorate writers, cities, artists, and histories. The first “Bukhara Night” in January 2006 honored Rabindranath Tagore — a favorite poet of Dehbashi’s late father. Since, “Bukhara Nights” have been held to honor Umberto Eco, Mahmoud Darwish, William Butler Yeats, the Polish essayist and poet Adam Mickiewicz, Hannah Arendt, Virginia Woolf, the Urdo poet Iftikhar Arif, and more. Some nights are organized around a theme: old Tehran; the art and poetry surrounding pomegranates; ancient Zoroastrian manuscripts; the Armenian Genocide; or Assyrian Literature.

Attendance is free and open to all. The auditorium where Dehbashi currently hosts “Bukhara Nights” has 110 seats, with an additional room that fits 50 chairs in front of a large screen display. If the guests are well known (a number of times Sayeh has agreed to attend) there will be people sitting on the floors and on the steps. There are no notices given for the event aside from an announcement on social media a day or two before. The Nights feature a combination of short lectures, musical performances, poetry readings, and documentary screenings — all that Dehbashi thinks will honor the topic fully.

“Bukhara Nights” have slowly gathered critical acclaim, to become some of the city’s most significant cultural gatherings. The Night of Baba Tahir, the 11th-century Persian poet from Hamedan, was organized as a book and lecture for Nasrollah Pourjavadi’s new biography of Baba Tahir. It was also an opportunity for the 200 people in the audience to hear Mohammad Souri. Wearing his usual cap and worn shoes, Souri described his in-depth research into the Hamedan School of mysticism from Baba Tahir to Eyn ol Ghozat. Nowhere else in Tehran would Souri find a public audience for a topic that is both so fundamental to Iran’s understanding of its own intellectual history yet so stubbornly ignored. Vocalist Shahram Nazeri poignantly sang a number of Baba Tahir’s quatrains at the end.

“Bukhara Nights” have slowly gathered critical acclaim, to become some of the city’s most significant cultural gatherings. The Night of Baba Tahir, the 11th-century Persian poet from Hamedan, was organized as a book and lecture for Nasrollah Pourjavadi’s new biography of Baba Tahir. It was also an opportunity for the 200 people in the audience to hear Mohammad Souri. Wearing his usual cap and worn shoes, Souri described his in-depth research into the Hamedan School of mysticism from Baba Tahir to Eyn ol Ghozat. Nowhere else in Tehran would Souri find a public audience for a topic that is both so fundamental to Iran’s understanding of its own intellectual history yet so stubbornly ignored. Vocalist Shahram Nazeri poignantly sang a number of Baba Tahir’s quatrains at the end.Other aims of Bukhara, one especially at the heart of Dehbashi’s work, is to honor those who have spent a lifetime on a particular branch of scholarship or the arts in Iran. On the night of legendary vocalist and oud player Abdul Wahhab Shahdi, one of the most widely attended to date, Sayeh came and cried during a speech recalling the hardships his friend had had to endure. Also present were Mohammad-Reza Shajarian, Iran’s most celebrated living classical lyricist, tar player Houshang Zarif and ney master Hassan Nahid. All knew Shahidi closely and spoke fondly of their time working with him. Dehbashi had spent well over a year trying to bring all five men in one room before Shahidi. “Bukhara Nights” link past and present, honor all that was and all that was lost, and link a new generation to the intricacies of what was before them.

¤

Dehbashi is seen foremost for his work in literature and the arts within the Persian speaking cultural realm, “beyond the political” as he routinely reminds. But where exactly does the literary end and the political begin? Some of Iran’s most notable 20th-century poets were exiles or prisoners. Somewhere in the calling of the writer or intellectual is the negation of reality as promoted by the state. Dehbashi can never be far from the censorship apparatus.

He is now in court for the second time, over the publication of a poem in Bukhara that authorities deemed disrespectful to women with chador. This bears heavily on him — a ruling might close down the magazine. Dehbashi’s gatherings too are continuously under scrutiny. Often the guests speak on a whim, on a whole range of topics, both socially or politically taboo.

“Bukhara Nights” was launched in 2006. Weekly conversations with writers began as Thursday Afternoons at Bukhara in 2008. Among his early guests were the vocalist Pari Zangeneh, cultural theorist and scholar Dariush Shayegan, Tudeh activist turned critic and writer Anvar Khamei. Afternoon events, which Dehbashi hosted at his office, were brought to a standstill when the hardline newspaper Kayhan published a story titled, “Thursday evenings with the Freemasonry.” He subsequently organized Tuesday Mornings at Nashr-e Sales at the café on the upper floor of Sales Bookstore. He had to stop those meetings when the manager of Sales was called and told not to let Dehbashi in. Then, came the Afshar Foundation.

Mahmoud Afshar and his son, Iraj, with which Dehbashi was particularly close, were prolific scholars of the Persian language. They were also descendants of wealthy merchants of Yazd. In north Tehran’s upscale Valiasr Avenue, home to Iran’s highest priced real estate, lies Mowqoofat-e Mahmoud Afshar, the religious endowments that Mahmoud left for the publication, presentation, and propagation of scholarly and literary works of the Persian language. The home that Mahmoud Afshar and his wife shared has since been turned into an auditorium. The endowment saved the house from becoming a high rise. Dehbashi has been able to use that space to host “Bukhara Nights” and weekly conversations. The head of the Mowqoofat is cleric Ayatollah Mohaghegh Damad, academic and researcher, involved with both university and research institutions like the Center for the Great Islamic Encyclopedia established in 1984. Mohaghegh Damad is one of the only clerics to regularly appear at Bukhara.

Dehbashi, as anyone else closely involved with independent publishing, is also on the forefront of political disruptions. He has, often miraculously, been able to carry forward from the presidency of reformist President Khatami through the very tumultuous Ahmadinejad years when government played a much more prominent role in censorship. Mohammad-Ali Ramin became the Press Deputy at the Ministry of Culture under Ahmadinejad, tasked with leading an unprecedented shutdown of newspapers and magazines, while Ahmad Bourghani held that post in the Khatami administration. The media and publishing community, including Dehbashi, remember Bourghani fondly. “He took my side when Kayhan called me a freemason. Told them that what they really wanted to do was shut me down with baseless accusations.”

¤

Underlying much of Dehbashi’s work at Bukhara lingers an uneasy feeling that the Persian language in Iran no longer has such committed custodians as it once did. Most specifically, university and publishing institutions, who in tandem gave rise to the best literary productions of the 20th century, do not produce writers and scholars of national and international stature as they once did. Shafiei Kadkani is the last of University of Tehran’s famed literature professors, a department where scholars like Badiozzaman Forouzanfar and Abdolhossein Zarrinkoob once taught. Literary magazines like Bukhara are not as prominent as they once were. Kadkani and Ebtehaj belong to the “golden age” of contemporary Iranian poetry and scholarship, which often feels like a bygone era.

Can the nascent literary enthusiasts of today be connected to the generations before them? Dehbashi’s events, each in their own way, attempt to bridge the old with the new. He has been walking the streets of Tehran for decades now, organizing, hosting, editing, and publishing, despite the buttons that have been yanked off. One wonders how long the shirt, and the man wearing it, will hold.

¤

Pedestrian is a writer from Khuzestan, in southern Iran. Across and over clashing, intersecting, and merging borders, she now lives between Iran and the US.

LARB Contributor

Pedestrian is a freelance correspondent in Tehran.

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Nobel Tradition: Rabindranath Tagore — the First Songwriter to Win the Prize

Caroline Eden appreciates the work of Rabindranath Tagore, a songwriter who won the Nobel Prize decades before Bob Dylan was born.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2016%2F05%2FBukharaNight_Shahidi-1.jpg)