I was 29 years old when I saw Velázquez’s portrait of Góngora in Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. Until then, I had imagined other people were lying — let’s say, fooling themselves — when they expressed strong feelings about visual art. My mother cannot smell: I could not see.

Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599–1660) is a giant, to be classed with Michelangelo, Raphael, da Vinci, Dürer, Bernini, Goya, and other titans. It is always a good use of time to think about Velázquez.

The poet Luis de Góngora y Argote (1561–1627) is interesting, but he is not a pillar of our tradition in the way Velázquez is. After his so-called “Prince of Light” phase, Góngora devoted himself to knotty, allusive complexity, and earned the nickname by which he is remembered, Príncipe de las Tinieblas, “Prince of Darkness.” Like Faulkner’s, like Kafka’s, Góngora’s style has its own adjective. Thirty years later, I still hear Srta. Geile with her little hand puppet, Teodoro, saying Gongorismo. What can that be, I wondered.

I enjoy Góngora’s Soledades, but I do not admire them. They are overwrought.

El bosque dividido en islas pocas,

fragrante productor de aquel aroma

— que, traducido mal por el Egito,

tarde le encomiendó el Nilo a sus bocas,

y ellas más tarde a la gulosa Grecia —,

clavo no, espuela sí del apetito,

— que cuanto en conocello tardó Roma

fué templado Catón, casta Lucrecia —,

quédese, amigo, en tan inciertos mares,

donde con mi hacienda

del alma se quedó la mejor prenda,

cuya memoria es buitre de pesares.

Egypt and the Nile, Greece and Rome, Cato and Lucrece: eight percent of 75 words. Góngora’s structural complexity is exciting (as the avant-funk guitarist Mister Gravity once said to me, “Yo, Bach has mad riffs, boy”), but his allusions are relentless. He is always pointing elsewhere. It is as if he wished not merely to be situated among but to disappear behind his associations.

To say nothing of the bombast.

Auden goofs on it in The Portable Greek Reader.

Medea. This with a wife, or knowing not the couch?

Aegeus. Nay, not unyoked to wedlock’s bed am I. […]

Medea. Are you married or single?

Aegeus. Married.

Herbert Spencer asks, “[W]hat is bombast but a force of expression too great for the magnitude of the ideas embodied?”

Alberto Manguel says, of Soledades, “It is obvious to most readers that the essence of these verses is not in the story but in the telling of the story, in the voluptuous verbal construction.” I think of The Last Psychiatrist:

Psychopaths are an endless stream of words. They talk, they talk around, they talk around and around the actual point […] drown you in endless, pointless, but seemingly earnest talk about other things […] You know it’s bullshit, but civility, or insecurity, force[s] you to sit there and listen. It wears you down […] When I do an eval for a criminal trial […] you ask, “what time did you get to the house?” and for the next twenty minutes, you never hear the words “time” or “house” come out of their mouth.

But putting Bach and Auden to work in this brief article is not so different from Góngora’s enlisting Cato and Lucrece, is it?

¤

What I love most in Velázquez is his backgrounds. It was Jacques-Louis David’s The Death of Marat (1793) that taught me to ask: Where is this happening? — Where did Marat die?

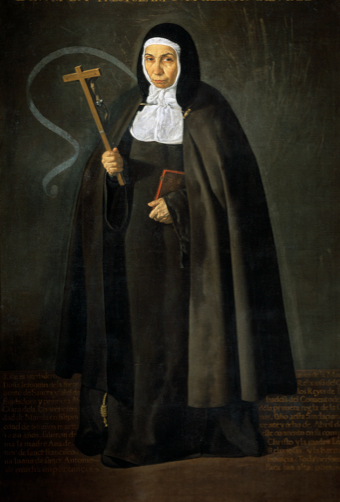

Where is Madre Jerónima de la Asunción (1620) standing?

Where is Madre Jerónima de la Asunción (1620) standing? Where is The Buffoon Pablo de Valladolid (1636–’37)?

Where is The Buffoon Pablo de Valladolid (1636–’37)?

I love the light Velázquez paints on Góngora’s forehead, and the shadow at his temple. I love the fold at the right shoulder of his cassock and the crease in his collar. I love the strange strokes of darkness, a downward streak and an open wedge, visible to the viewer’s left of Góngora’s ear.

More than all of this, I love that Góngora — densest, most clotted epitome of horror vacui — floats in Velázquez’s void, amor vacui. I love that Góngora’s attempts to flood his poems and his world with meaning trickle out into emptiness. It is a fact.

Where is this happening? In the void. — “The usefulness of a cup is its emptiness.”

Dan Hicks asks, “How can I miss you when you won’t go away?” Douglas Coupland says, “For me this apartment is full of nothingness […] I hoard space.” Pierre Bayard says, “Non-reading is not just the absence of reading. It is a genuine activity, one that consists of adopting a stance in relation to the immense tide of books that protects you from drowning.”

Lack is the necessary ground of desire. Desire leads to creation: to hallucinating, to rebuilding a lost object of desire. Presence annihilates lack.

See also: Necessity is the mother of invention. Fortunately, life is impossible.

¤

J. D. Daniels drove through North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas for Esquire before the 2016 US Presidential Election; his collection The Correspondence was published by Farrar Strauss and Giroux, by Jonathan Cape UK, and Suhrkamp Verlag in 2017.

LARB Contributor

LARB Staff Recommendations

Histories of Violence: The Violence of Art

Brad Evans speaks with British-born artist Jake Chapman, one half of the Chapman Brothers. A conversation in Brad Evans’s “Histories of Violence”...

Regarding the Pain of Trump

What Susan Sontag might say about Trump’s response to the Syrian Civil War.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2018%2F01%2FDanielsVelazquez.png)