Lazarus by Greg Rucka and Michael Lark

It’s nothing new to note the enormous levels of money and power possessed by the super rich. What’s perhaps newly striking in 2017 is how the features of colossal wealth have blurred the boundaries that separate science from magic, and political power from omnipotence. If Kobe Bryant — a mere multimillionaire — can have his platelets “washed” in a lab in Germany to buy two more seasons in the NBA, and basic bro venture capitalists have “blood boys,” what could Jeff Bezos have done to his body? Did he get those arms through protein paste and kettle bells alone?

Consider, too, the dark money politics that accompany such economies of scale. If the brothers Koch can torque dozens of local and state elections and fund what amounts to a half-decade-long obstructionist movement in one nation, what might happen if the families Slim, Koç, Ambani, Ferrero, Bettencourt — to name several of the richest in the world — joined the Kochs, and others, and decided to flip the game board of geopolitics over?

This is the premise of the comic series Lazarus, which began publication in 2013 and whose fifth collected volume appeared in June. The series, created by writer Greg Rucka and artist Michael Lark and published by Image, depicts an unblinkingly plausible slide into dystopia brought about by the concentration of wealth in a few hands. In the mid-21st century of the series, China has stumbled economically, and its vast stores of Western debt have become toxic. Various private armies circle each other in resource-rich regions, vying for oil in Indonesia and for rare earth minerals in the horn of Africa. In the United States, a contested election and blanket crop failures yield a pair of military coups and the privatization of major metropolitan areas. A tech dynasty in England seizes the United Kingdom, buys itself an aristocratic lineage, and transforms four nations into Great Britain and Ireland-Made-One. The most powerful family in Israel and its equivalent in the Arab Gulf set aside centuries of conflict in the name of seamless modern commerce, merging into one “family.” A Brazilian meatpacking dynasty takes over South America. A Swiss insurance conglomerate grabs the German-speaking parts of Europe. And so on and so forth, as the wealthiest dozen families around the world decide to do away with nation-state intermediaries and run things in their own interest.

The Macau Accords — a name as perfect as one can find in this sort of dystopian saga — act as the book’s feudal-capitalist version of Sykes-Picot and Westphalia. The families lay down new borders and set new terms for all “non-family” members, roughly 99.9 percent of the world’s people. The Accords divide them into two categories: “serfs,” the skilled workers like scientists, engineers, and media propagandists who live acceptably well-off lives; and “waste,” the bulk of the world’s population, who toil as de facto sharecroppers for a family or wander in destitution.

In a recent interview with New York Magazine, William Gibson noted that where once dystopian fiction speculated about life a few centuries in the future, he now finds it ominous how seldom we see the setting of “the 22nd century” in contemporary work. Lazarus fits perfectly in this landscape, its near-future world all too plausible except, perhaps, for its glitziest, most wholly imagined element.

Each family in Lazarus has, well, a Lazarus: a family janissary, bodyguard, mascot, field commander, champion, and herald with more-than-human abilities. Some have been gene-treated, some take Nth-generation pharmaceuticals, some have had body parts or entire organ systems replaced with robotics. Need to boost your army’s morale and seize a particularly important piece of territory? Send your Lazarus. Want to settle a diplomatic or legislative dispute between families? Have the Lazari (the comic’s preferred plural) fight one-on-one. Want to demonstrate your family’s prowess in gene therapy, cybernetics, pharmaceuticals, or general excellence? Gussy up and trot out the Lazarus.

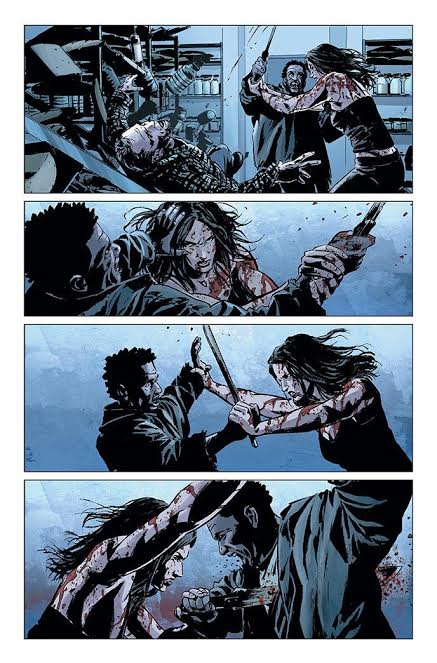

The series focuses on the Carlyle family, a mash-up of the real world Mercer family — the spooky libertarian financiers recently profiled in The New Yorker — and any number of West Coast tech dynasties. In the world of Lazarus, the Carlyle family is first among equals, and controls the western half of the United States. The series’s protagonist is Forever Carlyle, the family’s Lazarus. As Lark draws her, she is an imposing, furious warrior who looks like Hope Solo wielding a katana.

As majestically as Forever fights, she plays the black sheep in her own family. She’s desperately eager to please her distant father. She’s grumpy with her siblings — though to be fair, these are people who regularly dose her with new drugs in order to enhance her “systems.” Forever’s mysterious birth story, flashbacks to her training, and a snakebit romance with the Lazarus of a rival family make up the series’s perpetual b-plot.

You could imagine how, in other hands, this might collapse like a gassy summer tent-pole film or a Mark Millar–ish “edgy” bro-down among the ultra-rich. There would be swords, rich people in rooms that look like Apple Stores saying awful things about the existentially suffering poor, billion-dollar super soldiers questioning their own identity but still killing anyone they’re told to. Such a worst-of-all-possible-worlds version of the story would have only aroused reader’s interests in the dullest ways. It would have felt like ticking off the levels of a particularly passé video game. But Lazarus tries to do more than that. To the extent that the series succeeds in troubling the waters between the social pique of good speculative fiction and the exploitative thrills of watching rich peoples’ samurai get medieval, credit should go to creator and writer Rucka.

¤

Rucka has been positively voluble when it comes to the political urgency he’s imbued into Lazarus. To read interviews with him, and to read the interstitial material in the two hardcover editions of Lazarus that Image has published thus far, is to listen to a man on a mission.

In an essay accompanying the issue that closed the series’s most recent arc, and that’s made the comic world rounds online, Rucka writes:

Lazarus was born out of a fear of what happened when capitalism supplanted democracy. When the acquisition of wealth was the end of itself. That was how you got the world of Year X [the year in the comic’s timeline in which the Macau Accords go into effect].

This is precisely what we’re watching right now. A media machine that saw profit in Trump, and gave him all the publicity he could dream of for free, because it drove ratings, and ratings drove profits. A presidency that is shamelessly monetizing its very office, and a First Family that is leveraging their position to do the same. A deal that suddenly puts Trump brands in China after years of Chinese refusal; a 19.5% share in the recently-privatized Rosneft, sold to unnamed buyers, facilitated by Putin; the return of the Justice Department’s use of private prisons; a newly proposed budget that will ultimately dump billions and billions more dollars into the hands of a select few under the guise of bolstering the military.

This in itself is nothing particularly fresh. But Rucka’s not wrong, either. His description sounds like the generalized anxiety of a thousand Twitter feeds, but genuinely right-headed people and well-intentioned political parties around the world echo his concerns. If Frank Miller can embody the Brutalist–libertarian fantasy axis of comics, maybe Rucka, and by extension Lazarus, can occupy something closer to Occupy. Maybe.

Throughout his career, Rucka at his best has explored the space between institutional rigidity and individual choice, limited as this space may be. His DC series Gotham Central took the garish, blunt world of Batman and built a superb set of stories around the rank-and-file cops of Gotham City’s police department. It was a deft move. Instead of morality plays about costumed strong men, we got ragged stories about tired beat cops trying to make rent or deciding if they could come out to their family. Then they’d catch a case, chat over reheated, brackish coffee, go to the scene, and find Mr. Freeze. Rucka’s Joker didn’t have garish monologues. He used a bolt-action rifle to terrorize cops during a snowstorm. These moments of absurdity and horror sizzled in the context of Rucka’s workaday narrative. Lazarus flips Gotham Central’s absurdism/realism ratio, but Rucka’s drive to push against the quotidian continues to give his work its finest moments.

In Lazarus’s second and best arc, “Lift,” we meet the Barrett family, “waste” farmers in Montana, deep in the heart of Carlyle territory. Essentially sharecroppers, the Barretts enter the series as their farm floods. (Lazarus implies, if not directly states, that storms are more brutal and agriculture more untenable in the series’s world because of climate change.) The family “manager” in their area fails to deliver sand bags, they lose their farm, and they face a choice between taking out a back-breaking set of loans from the Carlyle family bureaucracy or forfeiting their worldly possessions and hitting the road.

They head for the Carlyle “lift,” the comic’s amped-up version of China’s Gaokao, or National Higher Education Entrance Examination, in which adolescents submit to a battery of tests and inspections to see if they might become serfs to the family. All manners of horror and suffering hit the family on the way to the lift. The end result? One child, Michael, is lifted to Carlyle-owned Stanford to become an engineer/doctor/mechanic for Forever. From rural stagnation to futurist pilgrim’s progress to triumph in a competitive admission process to a lucky, lucky life of service — this is a mutated Horatio Alger story in four beats.

“Lift” also encapsulates the deepest tension of Lazarus because it offers the firmest possible context for the art of Michael Lark. Lark is the series’s main artist, as he was for the initial run of Gotham Central. In both series he supplies lean, warm images, and is as adept at drawing action scenes as he is at setting the scene for dialogue. He renders facial expressions with particular subtlety: Lark gives desperate-for-immortality patriarch Malcolm Carlyle a wine cellar’s worth of scowls, while Michael Barrett’s face goes from anxious to empowered in half a dozen issues. Lark’s talent for drawing faces as they listen and observe, moreover, amplifies Lazarus’s moments of noirishness and conspiracy. “Lift” takes the reader from rural poverty to scabby back roads to the bulging domes of a Carlyle compound. Lark’s steadiness makes the world cohere, and puts the realism and fantasy of the series on a visual sliding scale. He also keeps battle scenes uncluttered, in a manner reminiscent of the war photography of Chris Hondros or the films of Michael Mann. Violence is omnipresent in the series, but Lark rarely depicts it with any kind of leer — a pointed choice in a series in which swords swung by super soldiers meet body parts semi-regularly. But when there is a bout between Lazari, Lark can summon the flinty grandeur of a Douglas Fairbanks duel.

¤

But what does all this genre excellence and political pathos get us? We do, after all, spend the bulk of our time around the .01 percent and the people who kill for them. We can admire how Lazarus succeeds on a number of technical levels, admire how grimly astute its world building is, admire how its notes resonate. But does Lazarus thrill our visual impulses at the cost of petrifying our rational ones? After all, as Rucka himself has made clear, the comic is not supposed to be escapism.

In the end, Lazarus demonstrates the difficulty, if not impossibility, of telling an anti-tech, anti-futurist, anti-inherited-wealth dystopic story in a visual medium. It exemplifies a revised (rebooted?) version of François Truffaut’s maxim about the conundrum of antiwar war movies: they are too exciting and filled with triumph to convince the audience of war’s inhumanity.

Like the 1980s British comic Judge Dredd or the Hunger Games movies, the very nature of visually representing a dystopia compounds the problem, because the aesthetic requirements of the genre mask its political urgency. The ruling class, no matter how vile, will simply look cooler than the ruled. Exclusively textual depictions of dystopias like Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We allow appropriately wary minds to create fittingly forbidding images. We don’t have the same freedom with comics, movies, TV, or video games.

You can approach the series completely in sync with its political commitments, but when Forever Carlyle shakes off a grizzly rifle shot to the ribs and vaults over a tank like a super-powered Simone Biles, your politics may go dormant for a second or four. This tension makes for good entertainment — which Lazarus is — but can Lazarus’s creators really say they’re offering an earnest warning about neo-feudalism when the series makes the body armor look so good?

I don’t blame Rucka and Lark. The difficulty is baked into the genre. It’s extremely hard to guess what a truly political dystopia might look like. Typically, when an underclass triumphs against the existing order the story ends. There’s no blueprint for what comes next. And all too often, in life and in art, what comes after dystopia is more dystopia. Lazarus seems at points to be aware of this dynamic. In the most recent issues, one of the Carlyle daughters begins to conspire with Forever and Michael Barrett to overthrow the hegemony of the families. She earns Forever’s trust by showing Forever her true origins. (Spoiler: They involve a lab, there are replacement body parts floating in a tank, and Forever is not the first Forever.). In contrast, she earns Michael Barrett‘s help by threatening him.

We read Lazarus and see palace intrigue, super soldiers who have dark nights of the soul about their provenance and occupation (Forever’s love interest, the Lazarus from a rival family, actually says to her, in an intimate moment in the third issue, “I think they make us fight so they don’t have to”), barren land, favelas next to the Hollywood sign, and squabbles among the wealthiest people in the history of the world. Everything here feels simultaneously fanciful and troublingly plausible. But what then do we do? Root for the beautiful futuristic janissaries to kill the masters and set up a “better” government? Hope for an uprising by the “waste,” the people with whom we are supposed to identify, the people for whom but for the grace of God, we would be? I’d venture to guess that Rucka plans to bend the narrative in the former direction, and that when Lazarus wraps up we’ll be given a new, more just order and hopes for some kind of democracy — whatever that means.

I can’t shake the feeling that there’s an insidious undertone to the story, an undertone shared by all the dystopian stories about money and power that play out in images. I’m supposed to look at the cool, conflicted $6-billion warriors, but my mind keeps drifting. I keep thinking about Michael Barrett, thinking about all that he has to forfeit for safety: his family “elevated” from their farm to what remains of Nob Hill; his childhood sweetheart whittled into a trusted military protégé of Forever; his own life transformed from reading and laboring on a farm to a “better” existence of intrigue, billion-dollar labs, and tending to a super soldier.

So for all of the technical accomplishment and political gestures of Lazarus, I wonder if it isn’t quietly, unintentionally, nudging the same maxim toward me that a thousand other dystopian fables have: get rich or die trying.

¤

LARB Contributor

LARB Staff Recommendations

Dystopian Resistance: Christopher Brown’s “Tropic of Kansas”

Christopher Urban on Christopher Brown’s SF thriller “Tropic of Kansas.”

Monsters Come Home: On Marjorie Liu and Sana Takeda’s “Monstress”

Min Hyoung Song on what Marjorie Liu and Sana Takeda's "Monstress" can teach us now.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2017%2F10%2Flazarus.jpeg)