Srsly.

By Sarah MesleNovember 6, 2014

Texts from Jane Eyre by Mallory Ortberg

MOST MEN aren’t terrible.

Most men don’t condescend, don’t leer; most men are good and kind human beings. Most men I know respect women and have a healthy understanding of sexism and structural inequality.

What's more, both men and women have their choices curtailed by our culture’s gender norms. Even the categories “men” and “women” — these terms don’t really capture the diverse ways we experience gender and gender oppression.

The niceness of most men I know makes the claim I am about to make somewhat difficult. But here it is: I am regularly kinda pissed at men. So often, in ways big and small, men suck.

You’re not supposed to say that. Being categorically angry with men is unattractive, and it isn’t (given the basic human decency of most men) really fair. What’s worse, being angry isn’t effective. If you’re in the midst of dealing with a sucky man situation, expressing anger about sexism or structural inequality is the surest way to get yourself and your point of view relegated to the “crazy angry lady” category where your tone will be labeled shrill and your opinions summarily dismissed.

This is the conundrum many women find themselves navigating: we regularly experience an anger we can only partially credit and only in certain contexts safely or successfully articulate. That anger needs to go somewhere. It needs different modes. It needs, often, satire.

Into this emotional context enters a new book: Mallory Ortberg’s Texts from Jane Eyre. It’s a splendid and wry work of humor writing, but that is not its only merit. Comprised entirely of imagined text conversations with or between literary figures, Texts from Jane Eyre employs a clever conceit. But “the phones,” as Ortberg has said, “aren’t really the point.” Texts from Jane Eyre isn’t really another book in the mode of Pride and Prejudice and Zombies — a book I enjoy, but which stages the collision between high literature and mass culture as a joke for its own sake. Texts from Jane Eyre, by contrast, uses that collision to pointed satiric effect.

The better comparison might be that Texts from Jane Eyre is to literary culture what The Daily Show is to politics: both use satire to expose the contradictions and absurdity enabling powerful figures. And Ortberg’s satire matters because it is fantastically able to express women’s anger toward men: men both real, and imagined.

For those of us who first discovered Ortberg’s writing in the ephemeral wilds of the internet, the news that her “Texts from …” series would be published just in time for a major holiday marketing push was greeted as a wonderful sort of validation. Ortberg is the co-creater of The Toast, a “general interest website geared toward women.” She is also one of the most noteworthy figures in a vibrant internet culture of feminist writing, one marked by its interest in developing new forms for describing gender’s social power.

Given the internet’s serpentine genealogies, charting the tradition out of which Ortberg’s writing emerges is somewhat difficult, but I would point interested readers toward a few key source texts: Edith Zimmerman’s strange and blistering “Women Laughing Alone with Salad” and the dearly departed Jezebel series “Crap Email from a Dude.”

As these titles indicate, Ortberg’s writing comes from a culture that is both unapologetically and unconventionally political. Not all of her work is explicitly gendered — perhaps my favorite piece of hers is a list of “The Eleven Worst Plants” — but the intersection of gender, art (writ large), and social power is her great topic, and she returns to it almost weekly in posts exploring issues such as “Women Who Want to Be Alone in Western Art History.” With Texts from Jane Eyre, Ortberg’s writing is poised to reach a wider audience. This seems, then, a good moment to pause and take stock of the stakes of her project. Why texts; why Jane Eyre?

The title Texts from Jane Eyre sounds a bit like the book will offer equal-opportunity literary skewering — it doesn’t necessarily sound like an forceful piece of feminist writing. But in fact, the book focuses its ridicule mostly on the behavior of self-styled male geniuses, both authors and characters, who childishly demand that their genius be catered to, coddled, and reinforced.

Genius, of course, is not necessarily male, but Ortberg’s work makes us realize the extent to which the idea of genius — let’s mark it as Genius with a capital G — remains strangely masculinized; strikingly available to men regardless of their actual talent. The genre of the phone text, as I will discuss, becomes the form of text — text here in the literary sense — most able to reveal how social power and literary prominence align.

Practically speaking, what this means is that Ortberg’s Texts from Jane Eyre is not only a major work of bathroom humor reading, but also a significant contribution to feminist literary criticism. It is difficult to imagine another book that would both be a perfect stocking stuffer and an exemplary text for a seminar in literary studies.

¤

Consider David Gilmour. In the fall of 2013, Gilmour, a novelist and professor at the University of Toronto (he’s quite established, and in his mid-sixties), granted an interview to the journal Hazlitt to run in their “Shelf Esteem” series. It was jaw-dropping in its casual misogyny. Indeed, Gilmour offered up his sexism as a kind of integrity. Take for instance this infamous quotation:

I’m not interested in teaching books by women. Virginia Woolf is the only writer that interests me as a woman writer, so I do teach one of her short stories. But once again, when I was given this job I said I would only teach the people that I truly, truly love. Unfortunately, none of those happen to be Chinese, or women. Except for Virginia Woolf. […] What I teach is guys. Serious heterosexual guys.

Gilmour frames his pedagogy as both personal preference and objective aesthetic judgment. He teaches what he “loves,” but of course what he loves just “happens” to be only the “serious” work of “heterosexual guys.” His invocation of the “serious” is key; he is a serious reader of serious fiction; if women would “happen” to write seriously then certainly he might love them too. But of course, Gilmour’s categories are always already gendered: seriousness and love are fundamentally male, because maleness is fundamentally serious and lovable.

What was most remarkable for me about reading Gilmour’s interview was its explicitness; its content, I had certainly seen before. Of course I had: I am a professor; I study writing and literature. Despite what one is occasionally told about the liberal professoriate, smug dudes, with their smug dude assumptions about Genius, “seriousness,” and the “Chinese, or women” remain shockingly in evidence in your average university setting. (These smug dudes are usually also old white dudes — age and race exponentially exacerbate the problem.) On every campus I have visited, smug dudes roam around being casually or aggressively condescending. (Once, for instance, an elderly smug dude, in a gesture that he clearly meant as one of good will, publicly patted me on the head; I was 32.)

Managing these men is a daily fact of life of being a woman and an academic (let alone being an academic of color, or queer). My approach, which has served me well enough, is one of intellectual avoidance; at receptions, for instance, I try to steer conversation away from my work toward the snacks. “Oh, thank you for asking, so bemusedly, about my project! Have you tried a mini-quiche?”

Let me pause and say here: of course I love many literary dudes. They are not, all of them, smug and condescending. But let me say something else: I thought for a while that the really terrible ones were time limited — that they were products of the 1950s, of a particular time period, and that it really was a viable strategy to just talk about snacks until they all retired.

But I have now realized this is not true; new terrible smug dudes are coming up through the ranks. Hydra-like, smug dude attitude keeps springing forth from itself.

I can only conclude that we do not have the 1950s to blame for this terribleness. The problem is more pernicious. The problem is that so few men can resist partaking of the benefits of that structure for which they are still the symbols of seriousness. Spend enough time in this system, as a white dude particularly, and you come to believe in your own gravitas.

The symbolic association of manhood with seriousness — with Genius, with talent, with regard — has proved shockingly tenacious. Despite decades now of focused feminist critique, dudes still boom condescendingly at us. (Sometimes, they boom at us about feminism, which they feel uniquely able to explain!) Somehow the language of serious intellectual engagement has not been able to bring down the cult of Male Genius.

This particular failure of academic feminist writing — which is not to say that the feminist academy has not had innumerable successes; it certainly has — is the void that much internet feminist writing seeks to fill. Online, one finds various strategies for dismantling male seriousness: one I admire is Rebecca Solnit’s, which works as a sort of catalog of the often un-archived daily humiliations of writing-while-female.

Ortberg’s strategy, if strategy is not an inappropriately solid descriptor for Ortberg’s always-recursive rhetorical persona, is to actually inhabit the voice of male seriousness itself. She booms at us as men do, but to boom-dismantling effect.

Where I, as a literary critic, might straightforwardly explain and refute David Gilmour’s sexist logic, Ortberg’s response is to step into that logic, expanding it until its own precariousness becomes clear: in this case, she published an essay called “The Life of Virginia Woolf, Beloved Chinese Novelist, As Told By David Gilmour.”

Ortberg, writing as Gilmour, spins out a seemingly off-the-cuff account of Woolf’s intellectual merit:

Virginia Woolf was a famous Chinese novelist. She was born in China, as is so popular among the Chinese, where she was born. She came in third during the Boxer Uprising, after which she wrote The Good Earth, which was about China, while being a woman novelist.

Here and throughout the essay, Ortberg relies on repetition (“born in China […] where she was born”) to mock the self-congratulatory tone of Gilmour’s original interview: Gilmour imagined, one assumes, that his style served to emphasize and clarify, but in Ortberg’s essay the effect is to demonstrate that his ideas overall — particularly those about the (lack of) seriousness of women writers — are tautological.

This isn’t the only time Ortberg writes in the voice of the Male Genius, or rather in the voice that takes Male Genius as a given. In Ortberg’s hands, the serious dude worldview becomes an amusing place to visit, a sort of poorly run tourist site. Consider for instance her famed list “Male Novelist Jokes.” Without naming any male novelist in particular, Ortberg works to skewer all of them simultaneously.

Q: How many male novelists does it take to screw in a light bulb?

A: War is hell.

Q: How many male novelists does it take to screw in a light bulb?

A: [4000 words about an isolated encounter with a service worker that borders on racist and goes nowhere]

Is the object of this joke Hemingway or Pynchon, or the reader of Hemingway or Pynchon? It doesn’t matter; the joke is that male novelists inhabit a space where getting things done — whether the thing to be done is to screw in a light bulb, or to tell a story — can comfortably be ignored in favor of nurturing a sense of simultaneous suffering and self-importance. At least twice, Ortberg’s answer to the “how many male novelists” question involves the male novelists doing pushups: these shows of strength, like Gilmour’s tautologies, lift only themselves.

¤

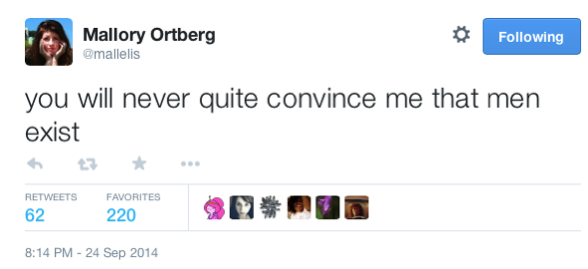

The internet, with its distractions and its slang, is often seen as precipitating the collapse of serious literary engagement. What Ortberg seems to have realized is that, to the extent that seriousness is coded male, the internet’s informal mode is less a problem than a feminist opportunity. Every attack that is made on the internet’s form becomes more fodder for the Mallory Ortberg dismantling-machine — take for instance this gorgeous June 1 tweet:

Responding here to an ambivalent New Yorker review of Patricia Lockwood’s poetry — and I should say that I don’t entirely agree with Ortberg’s take on that review — Ortberg turns Twitter’s form into a sort of imagist poem. The white space, the breaking syntax: in Ortberg’s hands, these perfectly illustrate the exhaustion of dealing with male reviewers who feel fit to judge the “real emotional depth” of women’s lives and forms. Ortberg shows why Lockwood, a poet whose most famous works are deeply feminist, would turn to Twitter in the first place, rather than a site of “seriousness” — like, for instance, The New Yorker.

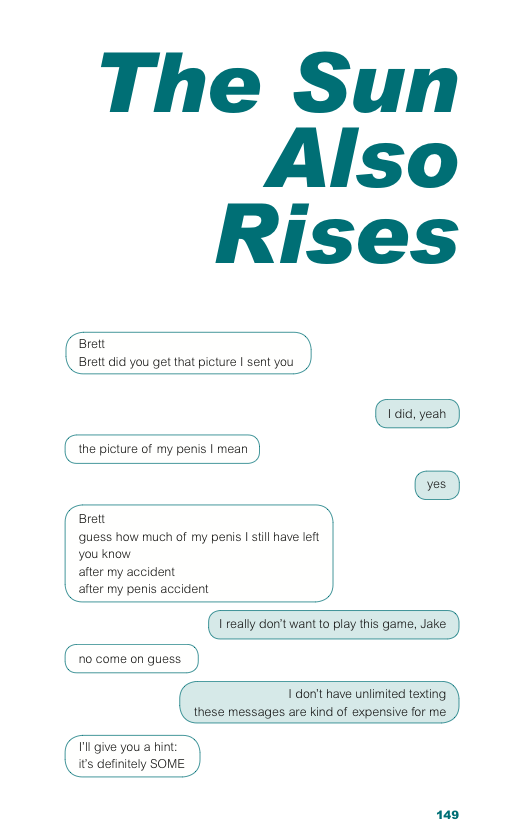

Like her tweet above, Ortberg’s Texts from Jane Eyre deploys the idioms of the digital age to recast debates about gender and seriousness. Let me turn to my question, above: why texts? The phone text, I think, is a genre where pragmatism and wit triumph, while grandeur and oratory annoy. Texts don’t pay much respect to seriousness. And thus, through them, Ortberg disables the seeming self-evident claim that seriousness, or Genius, merits recognition and support. Take for example this exchange Ortberg creates between Jake Barnes and Brett Ashley, central characters in The Sun Also Rises:

Where the cult of Genius stages niceness and practicality — “I don’t have unlimited texting” — as the opposite of the serious, Ortberg’s texts reveal these modes as strategies that women might use when men just won’t shut up. Again and again, Texts from Jane Eyre recasts this joke — the repetition, in fact, is part of the joke — of a woman dealing with the self-involved Male Genius, who reaches out only to suck her into a tiresome male drama.

Sometimes, like Hemingway’s Brett, the woman is named. But more often she’s a nameless figure (and I guess it’s possible that the figure is not necessarily a woman, except that the structure of the book implies the figure’s opposition to the literary Male Genius). Texts from Jane Eyre’s women have to, for instance, negotiate party arrival times with Edgar Allan Poe, and try not to hurt William Blake’s feelings as he attempts to bestow as a gift yet another unwanted drawing of a flaying. (“I just already have so many watercolors of flayings already,” Blake’s text correspondant says. “I wouldn’t know where to put another one.”)

Sometimes, on the other hand, the texts are exchanged between two women. These women range from the classical to the contemporary. (Ortberg, not bound by any limits of genre, moves with equal cleverness between Euripides’ Medea and The Baby-Sitters Club.) Here the niceness works differently. When Medea texts Glauce to say “hiiiiiiii” and that “‘Jason and Glauce’ sounds so good together,” we see text-world niceness not as a kind of vapidity, but rather as a small weapon that women are sometimes happy to use. Why not? Ortberg doesn’t endorse it, but she seems to show digital faux niceness as the sort of versatile tool one might use when other cultural resources — like Genius — are unavailable to you.

The best jokes, however, are those in which social equity isn’t just the text’s subtext but its overt subject. Tracking across stories from “The Yellow Wallpaper” to Gone With the Wind to the American Girl series, Ortberg imagines the silenced voices of American literary culture with phones in their hands. While much of the book (as much of this essay, I am aware) seems to play exclusively on the axis of gender, in these moments more complicated intersections of race and class come into play. The website for Texts from Jane Eyre jokes about “Scarlett O’Hara [with] an unlimited data plan,” but I will tell you that Ortberg is far more interested in what Scarlett’s slave Prissy might herself say about “not knowing nothing about birthing no babies.”

For the reader, the pleasure across the board here is basically one of revenge. It’s not always revenge on the character. (I personally have no problem with William Blake, for example — I really do like his flayings — and there’s a way in which the take down of so many characters in a row can get a little wearying.) Instead, it’s revenge on a system that has made particular responses to reading seem untenable, or necessarily unserious. There’s so little room to roll your eyes at these fantastic men; to say that they suck. And there’s a tremendous catharsis that comes from a whole book that encourages you to do so.

That is why, perhaps, it’s Jane Eyre who gets the book’s title. Jane Eyre is a key text in feminist criticism, and has been for nearly a century: Virginia Woolf discusses it in A Room of One’s Own, and the field-changing (and life-changing, for some of us) book The Madwoman in the Attic uses it as an ur-text for explaining how both literature and life have kept women’s talent caged. (I’ll note also this amazing discussion of Vilette by Carrie Hill Wilner.) I don’t know that Ortberg purposefully chose her title to bring Texts from Jane Eyre in dialogue with Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar’s book — though I would not be surprised — but it’s certainly the case that Ortberg’s title makes the association present for me. What can Ortberg’s texts teach us about Jane Eyre’s choices that a century of feminist criticism has not revealed? Or, let me put this differently: how does it change our sense of Rochester to find him texting to Jane in all caps: “I KNEW IT / DID YOU LEAVE BECAUSE OF MY ATTIC WIFE / IS THAT WHAT THIS IS ABOUT?”

What do we make of Rochester’s all caps? In them, in Rochester’s description of Jane as his “POCKET WITCH,” I see Rochester … booming. And then, a moment later, St. John also booming, about “these TWO TICKETS TO INDIA.” Rochester and St. John both boom at Jane, as though to make their fantasies of who she is more real. Ortberg’s reader sees Jane positioned between two men who share a sense of entitlement about Jane’s future. This is not a new claim, exactly, but for me Ortberg’s idiom made available a mind-changing encounter with Rochester: I will teach Jane Eyre differently now.

Satire resists analysis: that’s its job. So it’s hard to know where to stop with Texts from Jane Eyre. There is more to say about how Ortberg’s access to the internet’s satiric lower registers will change as she herself becomes more culturally prominent and powerful; there is, too, more to say about how Texts from Jane Eyre both resists and indulges “relatability” as a foundation of criticism or of reading. But I am not sure how to say these things without slipping too far into a mode of critical seriousness that’s completely antithetical to the humor of Ortberg’s work. Suffice it to say that I think Ortberg is doing something new with feminist prose, and that one good effect of her prose’s success will be the calling forth of a new kind of feminist criticism: one less worried about its friendliness.

However, it’s worth anticipating at least one possible criticism of Ortberg — that her dismissal of men and male behavior is too wide-sweeping. I can imagine being a male novelist, or even just an actual male, and finding Ortberg wearying. Her condemnation of men writing, and also men reading, is so sweeping that it borders on farcical. Isn’t it man-hating? Isn’t she reinforcing the stereotype that feminists, and feminist critics, hate men? Shouldn’t she be more nuanced? Shouldn’t she acknowledge more fully how many good men there are in the world?

Here is my response: I turn to Ortberg’s work in moments when I have been patted on the head by older men who don’t see it a problem that they will never imagine me as more than a child; when I am told (overtly or implicitly) that whatever I do it will never be as important as what a man does; when yet another male talent is revealed as abusive and the world fails to respond. I turn to Ortberg when I, like her, feel rather proud to wear the “misandrist” mantel. I turn to Ortberg when I want to say to the men I love that “your request of ‘gotta hear both sides’ has been denied.”

Ortberg dismantles Male Genius so effectively that she allows her readers to create an imaginative space outside of male seriousness; this is her appeal. In the space she creates, Male Genius is not so much a powerful symbolic order as a self-involved and bumbling habit, one that we might easily leave by the snack table while we get on with the more serious business of living dynamic creative lives. As Ortberg recently said on Twitter:

Reader: at moments like this, I would marry her.

¤

LARB Contributor

Sarah Mesle (PhD, Northwestern) is faculty at USC and Senior Humanities Editor at the Los Angeles Review of Books. Prior to arriving at USC, she held postdoctoral fellowships in English at the University of Michigan and the University of California, Los Angeles. She is a 19th-century Americanist by training and is interested, generally speaking, in the long history of the American popular novel and in the many ways pop culture can excite, estrange, and surprise.

With Sarah Blackwood, she is co-editor of Avidly.org. You can follow her on Twitter.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Miserablism and Resistance at the American Studies Association

Sarah Mesle interviews David Roediger about the 2015 American Studies Association conference and ASA's relationship to social action.

America Hates Women

Bad Feminist brings an inclusive and modulated voice to what has been, at times, a shrill conversation.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!