Sink or Swim: Corinne Mucha Strives to “Get Over It”

By Megan KirbyDecember 27, 2014

Get Over It! by Corinne Mucha

IN A SPLASH PAGE toward the beginning of Corinne Mucha’s heartbreak memoir, Get Over It!, cartoon Corinne hunches over as teardrops stream down her face. Waves of her own making rise around her, simple and effective in their crosshatched depth. She strikes a familiar image: Alice in the pool of tears, a woman literally drowning in her own emotions.

It’s easy to draw comparisons to Roy Lichtenstein’s iconic “Drowning Girl.” In 1963, Lichtenstein copped the splash page from romance comic Secret Hearts #83 for what would become his pop-art magnum opus. He’d recreated the simple lines and bright colors of pulp comics before (earning the ire of artists who viewed his borrowing as theft). In “Drowning Girl,” the teenage protagonist appears trapped in a wave, her tear-stained face barely visible above the water. Her closed eyes and languid fingers belie the ironic apathy of her conundrum: she’s being pulled under by the weight of her own melodrama. Above her sits a speech bubble as famous as the image itself: “I don’t care! I’d rather sink -- than ask Brad for help!”

The classic girl from a ’60s romance rag is caught in a whirlpool of love and heartbreak, but Corinne’s inner monologue sways introspective rather than melodramatic: “Crying, crying, crying,” she writes. “Though water does not usually glue things together. It pushes them apart.”

Of course, Corinne Mucha isn’t the love-struck protagonist from a 1960s romance comic. She’s a modern comics creator recounting her real-life breakup with college sweetheart Sam. She had followed him from Massachusetts to Chicago, where they settled into seemingly domestic bliss. Her memoir recounts the happy beginnings. An early series of panels establishes their easy intimacy: co-mingled laundry, a pair of toothbrushes, collections of drawings and notes. They furnish their apartment “the way children build a fort,” playing at being adults as they drag furniture in from curbs. Five months later, nearly three years into their relationship, they break up.

This all happens in the first four pages, setting the stage for the crux of Corinne’s crisis: not the breakup itself, but the drawn-out, complicated process of getting over the relationship. Telling (and selling) a breakup story is tricky. Too many sad-sack reveries or bitter obsessions risk alienating readers. (Who doesn’t flinch a tiny bit when that newly single friend calls — again — to detail a months-old dispute — again?) Yet Mucha doesn’t dismiss her years-long depression; instead, she embarks on a funny, patient series of conversations with herself to get to the heart of her desperation. She further takes the opportunity to examine her own flawed reliance on the romantic tropes immortalized in romance comics like Secret Hearts. In Get Over It!, the conflict isn’t in her relationship with Sam. It’s in her struggle to reconcile the end of their love with the promised “happily ever after” she planned on. “You were my only sure thing,” cartoon Corinne mourns in one understated but heartbreaking frame.

¤

When Jack Kirby and Joe Simon teamed up to write Young Romance #1 in 1947, they offered an alternative to testosterone-heavy superhero and detective fare. This first foray into romance comics cost 10 cents for 32 pages of Real Life Stories, and it flew off the shelves. Romance comics boomed during the first three decades of the Cold War, following in the formulaic tradition of Harlequin romances and radio dramas. Watered-down, G-rated plots were also attributable to the Comics Code Authority (CCA), the self-regulated system the comics industry adopted to ensure publications fell in line with 1950s-era morality. Between the CCA, which outlined committed, monogamous relationships, and the growing focus on youth culture, romance comics — aimed at young women readers — did pretty well for themselves.

The plots were always narrated by head-over-heels young women (although the comics were largely written by men). In cover illustrations, teenage heroines sprawled across beds in nightgowns, clutching framed photographs of unrequited loves. Sometimes they watched from a cracked door as their beloved embraced another. They cried perfect Hollywood tears. At the end of the story, the protagonist always, always got the guy. (It was, after all, mandated.)

The books targeted female readers who had drifted away once superhero comics became devotedly, unquestionably masculine. The successful strategy brought a huge number of female readers back to the scene.

Today, the myth of “meant to be” shows up everywhere from Nicholas Sparks novels to episodes of The Bachelorette. Even cynics aim for true love or sigh at star-crossed lovers. It’s no secret that relationships in reality are messier (and much more mundane) than any fiction would have you believe. Get Over It! takes a look at that rift.

The innocent, the flirt, the girl next door: the characters made famous in the romance genre exist here as plot devices in place of real people. In the aftermath of her breakup, Corinne tries on different archetypes. She stages elaborate performances: the polished, perseverant Woman Scorned; the sloppy Blubbering Betsy. These characters might as well have their own pulp-comic covers, taglines and all.

Yet tropes don’t mesh with anyone’s daily schedules, and will-they-won’t-they cycles grow stale in real life and fiction alike. Romance comics have simple conflicts and sappy resolutions: the heroine ends her quest in the arms of her darling, and all is right with the world. Real-life romance ties up in knots instead of tidy bows, and picking the snags apart becomes monotonous work many prefer to walk away from.

Corinne and Sam separate, reconcile, separate — while Corinne writes lists, rereads old journals, and painfully compares herself to Sam’s new love interests. In the midst of this cycle, Mucha’s style shifts abruptly. For two pages, she and Sam show up as crude drawings, just a step above stick figures. They’ve treaded the same territory so much that their encounters adopt the sketched-out quality of notebook doodles. Together, they become badly drawn versions of themselves.

Then the narrative snaps back to Mucha’s signature style. She struggles to fit into yet another role: the forgiving girlfriend reunited with her heart’s desire. “Let’s kiss until I stop feeling totally betrayed by you!” she declares as Sam’s arms encircle her waist.

The shift in style underscores the distinct unpretentiousness to Mucha’s drawings. Depictions of herself border on unflattering, with a tiny ponytail always sticking haphazardly out of the top of her head. Her thin lines and simple patterns strike a balance between childlike and whimsical. It’s a purposeful, modest style, though — slightly more embellished than John Porcellino’s minimalism and a bit more guided than Lynda Barry’s messiness. Without losing charm, Get Over It! always seems polished, with Mucha in full control of every panel.

The slight book is an excellent entry point to Mucha’s maturing style. Her drawings have always been purposefully slapdash, but now her lines feel more practiced. Small, quiet strokes of visual acumen — as simple as a well-executed pattern on a tablecloth — give Mucha’s distinctive roughness a reasoned edge. The eccentric humor born in her early mini comics and zines, like Buzz and I Hate Mom’s Cat, seems more confident here, too, so that even the most bizarre fantasy scenes feel well placed or even logical. Corinne the character appears totally unfazed when she goes on the fantasy game show Innocent Questions (hosted by a talking question mark). Because she so readily slips into these fantasies, they never feel out of place.

When Sam admits he cheated, Corinne’s situation echoes countless old-school covers. “Look into her eyes and read the answer to her question… ‘Can any man be trusted?’” reads the tagline of Young Romance #150. Tears spill from under the tortured heroine’s sunglasses. Reflected in the lenses: her lover, passionately kissing someone else.

It would have been easy to vilify Sam — after all, the romance genre nearly demands it — but Mucha balances his infidelity with details of why she loved him in the first place. Their relationship has a distinct personality, worth preserving at the surface level. Sam sings made-up Korean-pop songs in bed and holds Corinne on the couch when she cries. Even as she begins to reject the idea of destiny, she remains emphatic of her long-standing tenderness toward the man who broke her heart. “Thank you for being the kind of person who was truly difficult to get over,” she writes in an endnote to Sam.

Mucha touched on similar subject matter in My Every Single Thought, a zine that ruminates on her solo life. Her first graphic novel, 2008 Xeric Grant–winning My Alaskan Summer, focused on Corinne and Sam in happier postgrad days — working at her aunt’s bed and breakfast and eating halibut for a season in Alaska. The book serves as an interesting prequel to Get Over It! — a depiction of their lives with no hint of an oncoming breakup.

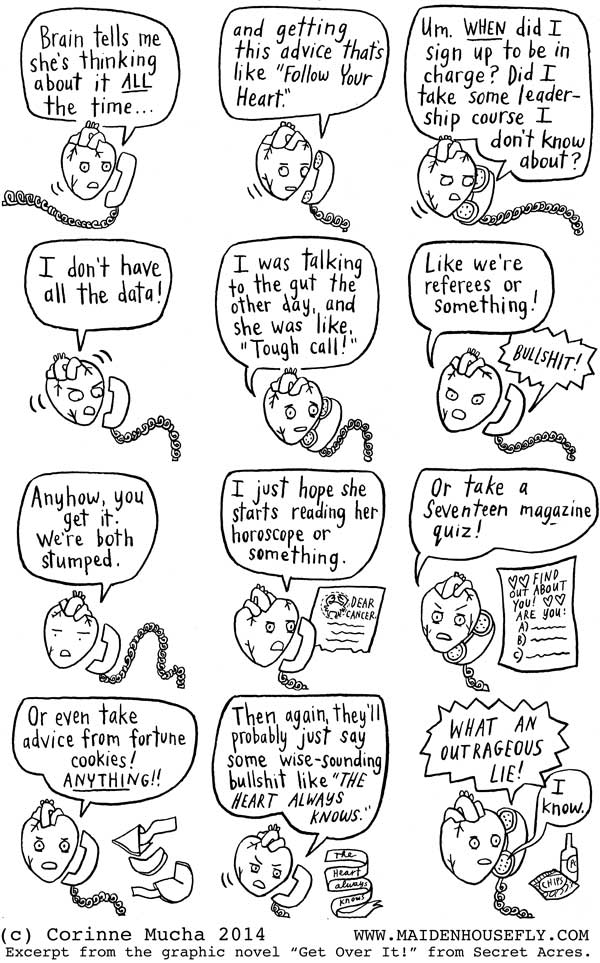

Her unique sense of humor balances a story that, at its heart, is very much about grief. Mucha’s constant use of wordplay, gags, visual metaphors, and childlike flights of fancy give her a self-aware edge. She balances difficult themes of grief and healing with a heavy dose of visual puns and irreverent humor, from Beyoncé references to surreal, drawn-out phone calls between her anthropomorphic heart and brain. She slips easily in and out of fantasy, with daydreams bleeding into reality.

If Mucha had tackled this comic in the midst of her breakup, the resulting story might have provided enough drama and heartbreak to fill a whole new run of Young Romance. But with the clarity born of time and distance, she’s crafted something extraordinary. A book about healing that never feels preachy. A look at depression that balances darkness with humor and tenderness.

Love affairs and breakup stories always have the same ingredients: infatuation, passion, chemistry, and dire stakes. The difference comes in the ending, and Corinne and Sam were never destined for a happy one. This is not a memoir about breaking up so much as it’s a story about letting go. It’s not really, therefore, a romance comic. It’s a story about self-discovery.

In the course of the book, Mucha depicts “getting over it” as a Chinese finger trap, a cat-faced clock, and a carnival game with only consolation prizes. But her strongest metaphor is also her simplest: “What does letting go feel like?” her protagonist asks. “Like you have a ball in your hand and you drop it. And you don’t chase after it.”

¤

LARB Contributor

Megan Kirby lives and writes in Chicago. Since moving to the city, she’s paid her rent freelancing for alumni magazines, walking rich people’s dogs, working a comic shop counter, and selling the occasional short story. She loves discussing feminism, geek culture, and the places where the two intersect. Over the years, she’s published a few zines. One of them is about The NeverEnding Story.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Approaches to Comics

Sara Lautman’s comic review of two other comics, by Leslie Weibeler and Dane Martin.

Truth and Permanence in the Comics of Bishakh Som

“I’M NOT INTERESTED IN TELLING THE TRUTH,” Bishakh Som says.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!