How to Paint a Battle and Think About War: Leonardo Vs. Michelangelo

By Michael KammenFebruary 3, 2013

The Lost Battles by Jonathan Jones

WHEN TWO OF THE GREATEST artistic talents of all time, living in the same urban hothouse, are enticed into intense rivalry by leaders and patrons of their community, the consequence is a consummate competition exacerbated by the politics of pride and instability. The ego-driven desire to surpass a rival can uncover suns of genius casting long-term shadows. In this particular instance, the artists happen to be the middle-aged Leonardo da Vinci and the zealous, energetic Michelangelo, a generation younger.

The place is republican Florence; the focal time is 1503 to 1506, with many implications far beyond, when the Medici family, tossed from power late in the 15th century, successfully schemed to regain firm control (they ultimately did in 1530). By then Leonardo had died in France as a self-imposed exile and court painter to the king, and Michelangelo had gone to Rome, first to build a mausoleum for the Pope and later to labor on his masterwork, the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Court painter to the Pope and hardly alone, he was one of the architects who figured out the math needed to raise Bramante’s immense dome over St. Peter’s.

Jonathan Jones — a Cantabridgian art critic for The Guardian and contributor to many magazines and newspapers, including the Los Angeles Times — has written a well-argued and well-informed page-turner about the artists and their rivalry that is infinitely accessible for the general reader. It is also little more than half the length of Rona Goffen’s very fine Renaissance Rivals: Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael, Titian (2002). Readers intrigued by The Lost Battles, as I am, may choose to follow up with Goffen’s tome. Jones’s is a treatise of political and artistic intrigue, crafted in muscular and arresting prose. He makes bold, provocative assertions that some scholars may not find entirely acceptable. Two examples:

Leonardo […] dressed almost exclusively in pink and purple, a delicate palette that harmonized with his own paintings. It was as if he were a character escaped from a fresco.

Surely this was a deliberate badge of professional identity — wearing colours that might have been mixed in his own workshop. […]

Michelangelo is the first artist who had a youth. That is, he is the first artist whose works seem to express his youthful experience of life — the first artist to become personal enough to express the passion, energy, ambition, and risk with which he seethed in his twenties.

Hmmm. Well, Praxiteles of Athens (4th century BC), for one, was once a precocious youth who sculpted astonishing nudes of both genders with considerable enthusiasm and genius.

Michelangelo carved his touching Pietà in 1500 at the astounding age of 25 and the next year received a commission to sculpt his monumental David, resolutely ready to slay Goliath, an emblem of manifold Florentine enemies. On May 14, 1504, it was first rolled out and displayed in the Piazza della Signoria, less than eight months after Leonardo had received his commission for a grand battle scene. Michelangelo’s award would soon follow. Machiavelli had a hand in both endeavors, not simply to be manipulative but because artistic competition at the highest level would benefit his republic.

(Leonardo did not want David to be displayed prominently, and in his notebook drew a metallic cover for the giant’s genitals: bronzed briefs for modesty [ornamento decente]! At some point he doodled an emasculated caricature of David. Yet in a late drawing related to his sensual painting of St. John the Baptist [Louvre], Leonardo depicted a long-haired youth pointing to heaven with an enormous erection — perhaps a dream about his ultimate destiny?)

At one point Leonardo would write that it was a boon for art students to work alongside others because that would inculcate a competitive spirit: “I say and say again that to draw in company is much better than working alone, for many reasons, the first of which is that you would be ashamed to feel inferior to the other students, and this shame will make you study well; secondly good envy [la invidia bona] [sic] will stimulate you to be among the number who are more praised than you, and the lauding of the others will spur you on.” Leonardo thereby offered a notion of “good envy,” the kind that can move an artist to excel. That’s exactly what happened in 1503–1506, but in this instance with an abundance of ill will.

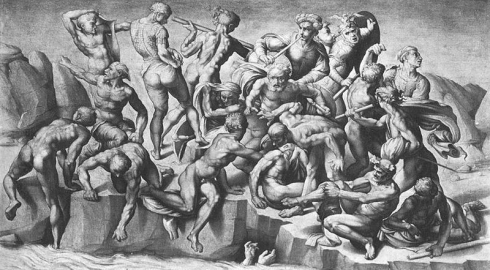

The lost battles in this book were enormous drawings, rather than finished paintings, of military triumph. Indeed, the two large works were commissioned in 1503–1504 to commemorate great victories by Florence: the Battle of Anghiari (1440) against menacing Milan, fought on the border between Tuscany and Umbria, and the Battle of Cascina (1364) with Pisa. Florence was not militarily strong in 1503 and indeed would be humbled less than a generation later. But it was a proud republic of citizen-soldiers as well as remarkable intellectuals and artists — the likes of Machiavelli, Botticelli, Filippino Lippi, Vasari, the young Benvenuto Cellini, and others too numerous to mention — a hall of fame with familiars. (See Martin Kemp, Leonardo da Vinci: The Marvelous Works of Nature and Man [2006], especially pages 227–40, for a factually succinct account of Leonardo’s project but not Michelangelo’s.)

Above: Peter Paul Rubens's copy of the lost "Battle of Anghiari," Leonardo da Vinci

Below: Bastiano da Sangallo's copy of the lost "Battle of Cascina," Michelangelo

Leonardo, widely recognized as a genius and brilliant draughtsman — his Mona Lisa was first shown to the Florentines in 1503 — received the Anghiari commission, while Michelangelo, just 28, understandably full of himself and arrogantly disrespectful of his senior, was given Cascina. They proceeded to work on their cartoons in private places, in very different ways, with various interruptions for other projects, and, as it turns out, with quite different aims in mind. The genius of Jones’s book lies in the way he uncovers and unfolds their idiosyncratic objectives, in the process riffing about the various all-stars we still celebrate (perhaps venerate) in Renaissance Florence. He uses written work by the artists and their contemporaries to reveal the meanings of the parallel projects, pursued pari passu. Late in life, for example, Leonardo wrote “How to Paint a Battle.” Michelangelo began to compose poems, increasingly as years went by.

The rivalry between these two masters ended only with their deaths, and even then it lived on in the minds of their followers. Raphael, eight years younger than Michelangelo, was an eyewitness to the contest, learned from both men and sought to incorporate the best of each in his own work. Jones puts it this way in describing the qualities the younger artist derived from his exemplary seniors:

Michelangelo is energy. The sideways, soaring movement of the child in Mary’s arms in the Bridgewater Madonna [by Raphael in 1507], the determination of Christ to stand upright — the strident, passionate fluency of Michelangelo’s art — is unmistakable in Raphael’s quotations. But this is balanced by the courtly Raphael with the softness of Leonardo, the yielding, enveloping quality of his compositions and his painterly delicacy of tone.

So how did the two cartoons differ — bozzetti in charcoal or black chalk — to ultimately be placed on facing walls in the Great Council Hall of the Palazzo della Signoria? What message did each artist want to send? What kind of story to be told? Leonardo was anti-war. At 52 he had witnessed too much of it. He was fascinated by furia, by the hatred that consumes men when they fight, and he had long been fascinated by the challenge of drawing horses in motion. So he concentrated his scene upon four riders and their massive mounts in the intense thick of battle — actually two against two according to Kemp. Horses and human bodies are interlocked, savagery contorting their faces. (Some of Leonardo’s preliminary sketches have survived at the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice and there is a surviving copy of the cartoon by an unknown 16th century artist.) Leonardo was all about the horrors of war.

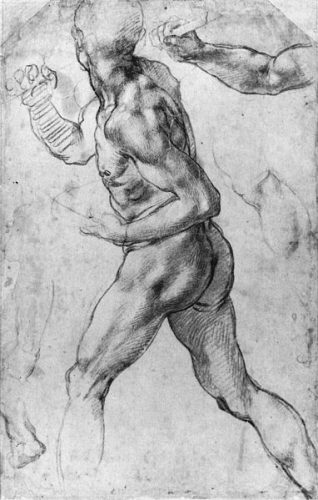

Michelangelo took a very different tack. As Jones makes abundantly clear in a chapter titled “Naked Truth,” he loved to paint muscular nude males with detailed attention to their anatomy. (Unlike Leonardo, he did not become actively homosexual with young men until later, after his beloved father died.) Rather than draw a fierce physical conflict in progress, as Leonardo did, he depicted fighters emerging from the River Arno where they had bathed prior to dressing and then armoring themselves for battle, either the next day or else directly following an emergency drill (again, see Kemp). Michelangelo was quite capable of drawing men in armor or fighting, but that seemed less beautiful than fully exposed figures in the buff. The appropriate apparel had been preshrunk, as it were. He did not glorify war, but as a citizen-patriot he made an enduring commitment to help defend his home place. Later, in the 1520s, he would design brilliant earthworks and urgent fortifications for Florence. Sound defense became an imperative.

Above: "Study of Two Warriors' Heads for the Battle of Anghiari," Leonardo da Vinci

Below: Michelangelo's study of "Battle of Cascina"

Once the cartoons were completed the next phase would involve putting them in place in the Council Hall, and Leonardo actually did erect a scaffold and began to paint. But working in the Great Hall was difficult because it was open for business and bustling, which disturbed the artist’s concentration. Moreover his paint did not adhere well and progress did not get very far. The moisture from a huge rainstorm was also ruinous. What remains beneath frescoes painted over by Vasari from the 1560s, restorationists believe, is a “great stain” that they are still hoping to uncover. Ultrasonic and thermal investigations have been made intermittently since 1976.

By the autumn of 1506 Leonardo’s relationships with the powers-that-be had soured, and he was out of favor. Meanwhile Michelangelo had become a favorite of the Gonfaloniere of Justice, named Soderini (like a Venetian Doge for life), and The Lost Battles pursues its saga of reputations rising and falling. Just three years earlier Leonardo had been an idolized figure in Florence, though clearly not by Michelangelo.

During the winter of 1512–1513 the Great Council Hall was devastated, witnessed by Benvenuto Cellini as a child. But half a century later he recalled what he had seen as a youngster:

This cartoon was the first beautiful work in which Michelangelo showed his marvelous talent [as a draughtsman], and he made it in competition with another who was at work there: with Leonardo da Vinci; the works were intended to serve for the Council Hall of the Palazzo della Signoria. They represented when Pisa was taken by the Florentines; and the admirable Leonardo da Vinci chose to show a battle of horsemen with the seizure of certain standards [banners], as divinely made, as it is possible to imagine. Michelangelo Buonarroti showed numerous infantrymen who because it was summer were bathing in the Arno, and in the same instant that the alarm was given he showed these nude footsoldiers rushing to arms, and with so many beautiful gestures, that no work by the ancients or moderns was ever seen to reach such a high mark, and as I have said, that of Leonardo was most beautiful and admirable.

Despite Cellini’s praise for Leonardo’s project, he declared that it was surpassed by Michelangelo’s, which was, according to Jones, “simply the greatest work of art in the history of the world,” a superlative that some are likely to challenge as over-the-top. From 1506 until 1512 the two massive cartoons remained on display, Leonardo’s in the Medici Palace and Michelangelo’s in the Sala del Papa in the convent of Santa Maria Novella. As Cellini insisted, “while they remained there, they served as the school of the world.”

I must mention the lengths to which Leonardo went in pursuing historical sources in the interest of accuracy and a specific sense of truth. Jones observes that the passion for historical research that Leonardo showed in his preparations to paint The Battle of Anghiari “matched his more famous love of scientific research. History was the favorite literary genre of the Humanists.” In his notebooks Leonardo argued, with literary Humanists in mind, that painting could narrate a complex event like a battle with even more immediacy than a written account:

But I ask no more than that a good painter should depict the fury of a battle and that a poet should write about it, and that they might be put in public where many people could see them and then we would see where the witnesses would look more, where they would give the most praise and which would satisfy them more; certainly the painting would please more, being more useful and beautiful.

I can concur about the superior aesthetics of art. Yet the compelling narrative prose of a Thucydides, or Francis Parkman, or more recently Garrett Mattingly, John Keegan, Jonathan Spence, or David McCullough, might very well be even more useful to the public because they are more fully elaborated than a painting, and the prose nearly equal in grace if not beauty. The public arts speak with many profound voices.

The cartoons were lost all too soon, largely gone by 1512. The one may have been torn up by enemies of Leonardo, hard to believe as that might be. More likely both were shredded by artists who tore off pieces of each as souvenirs or, even more plausible, as templates for their own works about horses and riders or nude bathers preparing for battle. The content of these cartoons remained well known, however; Leonardo’s use of art as an antiwar declamation has a direct line of influence to such greats as Rubens’s The Horrors of War (1637–38), Picasso’s Guernica (1937), Dalí’s España (1938), and many others.

Moreover, the competition cast a long and complex shadow in 16th century Italian art. Because the rivalry called upon the most intense ingenuity of each artist, a major legacy would be the swift emergence of Mannerism, a stylized mode of painting meant to highlight the ingenuity of the artist with fanciful developments. The two great painters shaped and influenced themselves as their work evolved. Michelangelo, for example, began work on the Sistine Chapel in 1508. His scene of the great flood there owes something to the Cascina’s soldiers leaping from the Arno.

The Lost Battles includes countless excursions and “side-bars” that fascinate and illuminate, such as various depictions of Judith beheading Holofernes, the issue of sexual inequality in Renaissance Europe, and the sheer size of the gay community in 15th century Florence. Leonardo may have been forced to leave for Milan in 1479, among other reasons, because he hosted a group of younger gay men, yet later he was accepted with his entourage because of his extraordinary value as a scientist and artist. Jones has an interesting short section on gay life in early modern Italy. (See also Michael Rocke, Forbidden Friendships: Homosexuality and Male Friendships in Renaissance Florence [1996], which Jones does not use. Donatello, Botticelli, and Cellini also had homoerotic inclinations. Rocke’s frontispiece shows a painting by Domenico Cresti, Bathers at San Niccolò (c. 1600, in a private collection). The numerous and boldly amorous males bring to mind Michelangelo’s men emerging from the Arno.)

There are informative passages about Leonardo as a brilliant architect and engineer, designing temples, domes, fortifications, bastions, and earthworks. Later we get the same tour-de-force treatment for Michelangelo as architect and designer of defenses. Jones provides a useful corrective to Sigmund Freud’s misreading of Leonardo in his biography of that complex figure. Last but not least, Machiavelli comes alive as an admirer of the ancients and a man who rationalized battle scenes as a call to arms and honor for the Florentines. As he wrote in praise of republics in The Prince: “There is greater vitality, greater hatred, more desire for revenge.”

The spiteful relationship between our two protagonists persists throughout. Leonardo created his kneeling and sexually charged Leda and the Swan as a riposte to Michelangelo’s nudes. Their relationship kindled excursions into can-you-top-this or I’ll-put-you-down exercises. Jones has a very fine summation of the sensual differences between the two men:

With his coiffed hair and his pink tights and his extravagant wardrobe, his equally finely got-up servants and followers, Leonardo simply repelled Michelangelo. There is real rage toward the older man’s blurring of male and female beauty, his strange sensuality and “family” in the younger artist’s responses to [Leonardo’s] Annunziata cartoon.

The more rugged Michelangelo rejected what he perceived as Leonardo’s effeminacy.

The subtlety and complexity of this sometimes-breezy book defies simplistic summation. It can be read for its historical understanding of art and of detective reasoning. It shows how genius can be soiled by pettiness. Let’s give Jones the last word. He deserves it:

Art can say the deepest things imaginable about life and death. It can speak with sublime, pure eloquence. And it can heighten the experience of the beholder, like a bacchic ecstasy. All this art can do, in the hands of Leonardo and Michelangelo […] [W]hat is crucial to understanding their competition in Florence is that both believe in a public vocation for art. And monuments and frescoes are the appropriate forms for an art that is about to ascend to its true nobility.

¤

LARB Contributor

Michael Kammen was the Newton C. Farr Professor of American History and Culture (emeritus) at Cornell University, where he taught from 1965 until 2008. In 1980-81 he held a newly created visiting professorship in American history at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes in Paris. He was an elected member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and served in 1995-96 as President of the Organization of American Historians. In 2009 he received the American Historical Association Award for Scholarly Distinction. His books include People of Paradox: An Inquiry Concerning the Origins of American Civilization (1972), awarded the Pulitzer Prize for History in 1973; A Machine That Would Go of Itself: The Constitution in American Culture (1986), awarded the Francis Parkman Prize and the Henry Adams Prize; Mystic Chords of Memory: The Transformation of Tradition in American Culture (1991); A Time to Every Purpose: The Four Seasons in American Culture (2004), Visual Shock: A History of Art Controversies in American Culture (2006), and Digging Up the Dead: A History of Notable American Reburials (2010).

He wrote prolifically for the Los Angeles Review of Books before passing away in November 2013. He will be missed.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Edward Hopper as Home and Homesickness

Hopper's reception abroad

Open Marriage Chez Clem: A Life with Clement Greenberg

MAX ERNST, A GERMAN SURREALIST and sometime husband of Peggy Guggenheim (the famously promiscuous art dealer), once overturned a fully loaded ashtray...

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!