Above: Albino child, Biafra, Nigeria, 1969, detail. Left: Shell-shocked U.S. Marine, Hue, Vietnam, 1968. © Don McCullin (Contact Press Images)

THE ONLY TIME legendary wartime photojournalist Don McCullin lost his nerve was in Cambodia in 1970. Caught in the relentless crossfire that was decimating the soldiers around him, he finally realized that “a negative is not worth my life.” He discovered that the Nikon next to his head had taken a bullet, while he’d zigzagged back to camp. Yet despite suffering something like a nervous breakdown that day, McCullin rallied and went on to cover yet more of the headline conflicts of the last third of the 20th century. By some charmed combination of guts, fate, resilience, and foolhardiness, McCullin survived to tell a half century’s harrowing tales of covering fighting in Cyprus, Beirut, Congo (“its awful, dark Conradian period”), in wars in Vietnam, Biafra, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and the civil unrest in Northern Ireland; of being one of the few photographers in Jerusalem during The 6-Day War, back for the Yom Kippur War, the first and second Iraq Wars, and other theaters of manmade horror.

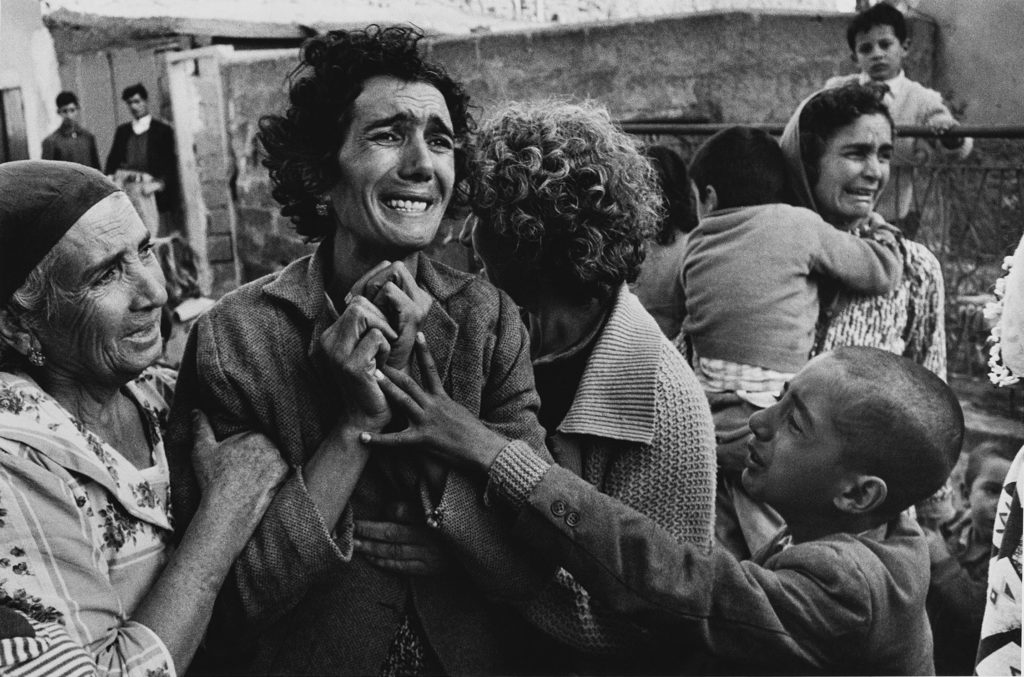

Turkish woman mourning the death of her husband killed by Greek forces during

civil war, Limassol, Cyprus, 1964 © Don McCullin (Contact Press Images)

Each destination yielded indelible black-and-white images that have informed minds and seared consciences around the world — as well as being annotations in McCullin’s own private hell. For him, there has always been an inner debate about the posture of voyeur in the face of human suffering and violent death. At times he was compelled to put down his camera and assist in some small way as best he could. (In Cyprus, he carried a frail old woman to safety, in Vietnam a wounded GI.) At other times he felt considerably less resolve for those he encountered. He promptly left Afghanistan upon discovering that the Mujahideen were stealing his gear. “I told the writer I didn’t want to die with that kind of dishonorable thieves.”

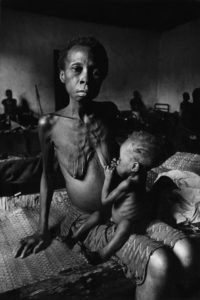

McCullin fought his own wars early on. Raised in disadvantaged circumstance in a tough district of North London, and losing his beloved father at 13, he hung out with delinquents, got in street scrapes, and didn’t bother much with attending school — a lapse of intellectual stimulation he would diligently remedy once he began working alongside newspaper writers. Apart from the compassion for the destitute and the victims of violence that he would take away from his turbulent youth, he recalls being shaken to the core by the postwar images of the Holocaust that began to appear in magazines. At 19, candid photographs that he casually shot of his home-turf gang made their way to the desk of an impressed editor at the Observer, and a stellar career was launched. His first series was self-initiated: the building of the Berlin Wall in 1961. Then, having served in the military in Cyprus, he was eager to cover his first international conflict there. As a young adrenalin junkie making his name in a medium that he took to with alacrity and preternatural artfulness, he saw these hot zones as opportunities to learn and experience. It was only after years of bearing witness to needless privation, grievous injury, mass starvation and bloody death that McCullin absorbed the darkness of it all, and viscerally reckoned with the fragility and transience of life. He endured periods of despondency, moral nausea, and “conscience nightmares.” Though he is revered as the heir to Robert Capa’s crown, he says, “I don’t wear my laurels comfortably.” He would title one of his books Sleeping With Ghosts.

Thirty-four-year old mother and child awaiting death,

Biafra, Nigeria, 1969 © Don McCullin (Contact Press Images)

The death of McCullin's father made it necessary to forego art school, but he remained a devoted autodidact, making drawings and paintings that developed his eye for compositional nuance, and for rendering light. He was profoundly inspired by Henri Cartier-Bresson’s ability to analyze and compose a scene in a fugitive instant, the sine qua non of a hotspot-chasing photojournalist. But he was equally imprinted with the art of Goya, his gift for rendering scenes that are at once macabre, political, and quasi-religious:

In the drawings of Goya, people are looking up as if waiting for God’s salvation, and He doesn’t come. I’ve seen so many people who have been executed and they call for God, they look up, particularly Islamic people. I’ve seen men shot point-blank in front of me and falling with the word Allah before they hit the ground. It’s the human body language that applies to this imagery of death or the moments before death. I tend to be more of an atheist. Having seen so much I find it hard to believe there is a God who will offer you that salvation.

Exhausted mother and child, in a camp on the border of India

and Bangladesh, August 1971 © Don McCullin (Contact Press Images)

McCullin’s eyes are, he says, his voice.

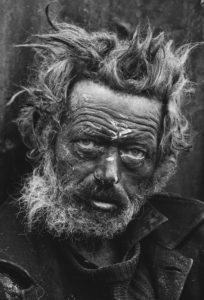

McCullin’s intensive globetrotting took a toll on his personal life, and his first family disintegrated because of his having placed exclusive priority on his work — not uncommon in that era, and in that profession. “I was inflicting my work and my sense of its importance on my family. I was not taking into consideration they had a life.” Years later he would sort through the resentments about his tough early life, become more self-aware and put things in perspective, he says. When he returned to England for good, more or less, he sought to reclaim his local identity and found another war to capture in his undaunted way: the impoverished denizens left behind in postwar Britain. He travelled around the country until fixing his lens on the industrial town of Bradford, and its indigent and homeless inhabitants, as a canvas for a grim social statement. Even the moody English landscapes that he has shot in recent years have an ulterior message: Pollution is destroying the exquisite pastoral scenes for which his emerald island nation is known, while farmers living off subsidies refuse to farm and food must be imported. “I can find a war anytime I want in any subject you choose to throw at me.”

Tormented, homeless Irishman, Spitalfields, London, 1969

© Don McCullin (Contact Press Images)

At 80, McCullin continues to reflect on the roads he’s taken, and remains as restless as ever (he recently returned from Syria). “The only ticket that someone ever gave me in life that was free was the ticket of fate. I’ve relied on fate to carry me through. Since 1961, 1000 journalists and photographers have been killed covering wars. Haven’t we learned our lesson?” Yet he subscribes to the notion that the core value of photojournalism, especially that practiced by the intrepid breed that comes face to face with atrocity on a regular basis, lies in its service to democracy. An informed citizenry needs to see and be outraged by these pictures of man’s persistent inhumanity, and perhaps in seeing the horror, they will prosecute for change. It is what continues to propel him. That and photography itself: “There is a kind of dynamo, an energy, in me which is arced by the name of photography, which drives me on, and even at my age I’m still having this love affair with photography.”

¤

Among McCullin's many books are Don McCullin: The New Definitive Edition, updated edition including 40 new unpublished photographs and a new introduction by Harold Evans (London: Jonathan Cape, 2015) and Irreconcilable Truths (2016), a three-volume boxed set of a limited edition of 1,000 numbered copies (the volumes are War & Reportage; Landscapes, Still Lifes & Travel; and Unreasonable Behaviour), 2016. It can be ordered at: http://donmccullin.com/.

LARB Contributor

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

![Don McCullin: Chronicler of Man's Inhumanity [VIDEO]](https://lareviewofbooks-media.azureedge.net/unsafe/3840x0/filters:format(jpeg):quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2016%2F09%2FMcCullin-caption-2.jpg)