In Memoriam: Carolyn See

By John Rechy, Lynell George, Lisa See, Susan Straight, Ron Charles, Laurence Goldstein, Jonathan KirschJanuary 13, 2017

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2017%2F01%2FCarolyn-See.jpg)

On July 13th, 2016, Carolyn See — novelist, critic, professor, and Los Angeles woman of letters — died in Santa Monica. Today, January 13th, would have been her 83rd birthday. To celebrate, we’ve gathered a few tributes and remembrances from her literary friends. Ron Charles, her longtime editor at the Washington Post, wrote a note in celebration of her 80th birthday; Lynell George writes an appreciation of her time as a student and then a friend; Larry Goldstein, former student, poet, and editor of the Michigan Quarterly Review, imagines her on her new perch; and John Rechy, one of Los Angeles’s literary lights, recognizes that same luminosity in a friend. In the eulogies they gave, Susan Straight invokes the singular characteristics of a mentor, while Jonathan Kirsch, author, good pal, and fellow Van Morrison aficionado, wraps her in white light.

— Lisa See and Clara Sturak

¤

For Carolyn, from John Rechy

¤

Eulogy by Susan Straight

Many of you here will know this — but I have to say it. When Carolyn talked to us on the phone, maybe telling us a joke or listening to us whine about writing or motherhood or New York, she’d laugh so hard you knew she was holding herself away from the receiver like Mariah Carey holding herself away from the microphone, and that pure sound would ring everywhere in the room. She had the most badass laugh of anyone I’ve ever known. She was my fairy godmother. About not finishing a book, about not finishing the laundry, about snobbery in publishing, she’d say, “Oh, honey, who really gives a shit?” and crack up until you did.

Because of Carolyn, I believed I could write about California. Her vision of our native place was like no one else’s. I was 22 when I read her novels and essays and wanted to be her. Carolyn See, Wanda Coleman, and John Rechy made me understand the beauty in places like ours — canyons with buckwheat and lizards, alleys with wild tobacco, streets with restless children who have come here for golden days. I could quote forever, but this line has sustained me:

I know it’s embarrassing to be from California, but here’s the other side: this state is the repository of America’s dreams; it is to America what America is to the rest of the world. If some of those dreams are tacky or inappropriate, that’s part of what I’m writing about.

That’s from Dreaming. I idolized Carolyn, and had met her only once. When she came to Riverside City College to read from Dreaming, I had published three books, but had no working car and three small children. I got a babysitter and walked down the gravel driveway of my old California bungalow, past the ancient Cecile Brunner rosebush, to the auditorium, and she began by reading the passage about her mother beating her near the pink Cecile Brunner roses in along the driveway of their California bungalow. I was trembling when she finished. When she was done signing, I introduced myself, and she laughed and laughed. She signed my book: My mom could beat yours — in an unfair fight. What do you say? Is it a bet?

Last night, I washed my car, because I was coming here. I was thinking about Golden Days and disaster, about how Carolyn saw dystopian futures long before they were popular. I haven’t washed my car for a year and a half. My neighbor walked up the sidewalk, carrying his own liquor in a lunchbag cooler as always; for 20 years, he’s lived in his sister’s backyard in his camper. He said, “Look at you! Drought must be over, right!” He said he might fill his empty above-ground pool now, since he wanted a better view from the camper, and I almost cried, thinking she’d love that story.

She was a fairy godmother to all of us. She was the first badass single mother native Californian writer I’d ever met. She knew we could save ourselves with story, with her elegant sentences and precise comic timing, with that laugh so powerful it was really a song.

¤

From Ron Charles to Carolyn on Her 80th Birthday

Dear Dear Carolyn,

If I hadn’t squandered away my Washington Post budget on new Kindles, I would be there in person to wish you a happy birthday!

For almost 10 years, I’ve had the pleasure of editing your witty, generous and insightful reviews. But you’ve been entertaining readers in the Washington Post a lot longer than that — since 1987!

Over those years, you’ve led us to so many wonderful books — and yes, you’ve warned us away from so many stinkers, too. But more than that, you’ve given us a sense of your wry wit, your incisive intelligence, and especially your generous spirit.

And how grateful I am for those times when you’ve called just to say hello and make sure I’m still fighting the good fight. Again and again, laughing for a few minutes with you has made all the difference. And I’m not even counting the time you called from the hospital all ginned up on painkillers and offered me a blow job.

To the only reviewer who calls me “Sugar Plums” and “Sweetums,” I wish you a very, very happy birthday and many happy returns of the day.

With love,

Ron

¤

Going the Distance: An Appreciation by Lynell George

The distance between writing and being a writer is deceptive. How close — or far — that goal appears can be a moving target. Making it to that destination depends on where you’re starting from and on whom and what you encounter along the way.

When I met Carolyn See as a junior in college, I already lived deeply in the landscape of words. I read and wrote daily — had done so for years — but it was mostly a private practice — something only my family and closest friends knew about.

Venturing out of that private space, I’d suffered a few bumps — teachers who couldn’t make heads or tails of me or what I was attempting to do on the page, writing about the people — often eccentrics, misfits or outsiders I encountered around Los Angeles — in compact word sketches, vignettes or lyric prose.

When I walked into Dr. See’s class at LMU — a course on magazine writing — she sat before us in a coral cashmere twin set and simple strand of pearls, and outlined her expectations with a soft lilt in her voice. I wasn’t sure what the ride would be.

I knew her name from the spines of books I shelved at the bookstore where I worked in evenings and on weekends during my college years. I also knew her byline from the LA Times. I loved how her essays in particular drifted through a Los Angeles I had some understanding of — in landscapes and characters and pace. Even the soundtrack — Gerry Mulligan, Warne Marsh and Chet Baker — were names I’d known from the backdrop of my growing up here, filtering through on the West Coast jazz LPs that spun on my mother’s own stereo.

Here before me was a real working writer. She treated us like adults and expected us to act as such. We were responsible for our stories — pitching ideas and embarking on the reporting, coming in with drafts to workshop. But the class’ shape changed — departed from any other I had had before — when it became clear a necessary percentage of our grade was based on taking part in the literary world. That might mean to pick and venture out to a reading, or go to one of Dr. See’s book events or parties. “You’ll meet people!” she encouraged.

There were times that her writing work took her away from class (she was working on Lotus Land at the time, with her daughter Lisa and her partner John Espey, under the winking nom de plume Monica Highland). In her absence, we often had someone come in and speak about writing or the writing life. Or we were expected to use the time for research — getting ahead on our reporting or writing. What I learned from Carolyn’s class was that we needed to be not just self-starters, but that we needed to keep the momentum going. Being a writer wasn’t simply about being in your head, it was about being in the world — connecting with people, shaping your day, shaping your destiny. I saw close up what it meant to be part of a larger conversation and where I might belong in it.

I turned in my piece, a feature about the then-illegal arts colony that was blooming in the old abandoned buildings not zoned for living in downtown LA. When she passed the paper back to me I saw the “A” floating in the white space of the top margin. Then she said, in that musical voice: “Dear, you could publish this.” I floated for weeks. This didn’t need to be a “private” thing. Those words helped point a clearer path for me.

Between graduate school, work and trying to sort out where that writer’s journey would take me, I wouldn’t see Carolyn in for another ten years. By this time, I had a book coming out and was working at L.A. Weekly as a staff writer. As a guest of a visiting writer friend, I’d bumped into her at the LA Times Book Prizes. Carolyn and I chatted long enough to learn that we would both be in the same collection of essays to be published later that year. My piece, I explained, was an outgrowth of the paper I’d begun in her class all those years ago.

With that reconnection, we began a different chapter of our relationship; she went from teacher/mentor to mentor/friend. I’d run into her at readings or be seated next to her on panels. I remember one in particular when young man thrust his hand in the air and asked Carolyn what was the best way to make money in the business. She paused and in that sweet-tea voice of hers said: “Well, dear, if that’s what your goal is, you’re really going after the wrong thing here ...”

Later as a staff writer for the LA Times, I was at once thrilled and terrified to write about her. After the profile ran, she sent me a lovely handwritten thank you note, just as she had always schooled us to do.

When too much time had elapsed between our chats and emails weren’t sufficient, we needed an in-person catch up, I’d meet her for lunch in Santa Monica at Michael’s. Later as her eyesight was challenging her, I’d pick her up and we’d head over for dinner at I Cuggini. But mind you, despite her compromised vision, she was always navigating, advising me when the turn was coming up and scoping out the best parking places.

More recently our ritual had been margaritas and tacos at Lula’s on Main Street, where we’d talk and laugh for hours about writing and writers and changing Los Angeles. She was always concerned about how things were going in my life — when the job front got rough, when my personal life was upended or when she thought someone angling for my attention was dangerous: “You know honeybunny, I think you need to be wary of that one, he’s a bit of a rapscallion!”

In last week’s flood of remembrances, I saw a quote of Carolyn’s I’d forgotten: “'When I started to write I was relatively old, and lived in California. So I was the wrong sex, wrong age, wrong coast. Luckily I was too ignorant to know it.”

I think one of the things that Carolyn saw in me was “the quiet girl who sat by the window” — and connected with — knowing precisely what it might be like to feel underestimated, to know full well what you had inside yourself that people might miss or refuse to see. But you keep going.

Earlier this week, I was clearing out boxes in my old childhood bedroom and my hand landed on that paper Carolyn had handed back more than 30 years ago. I’d saved it all this time.

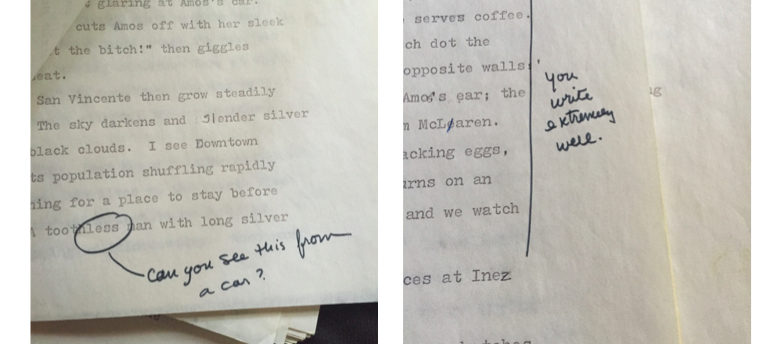

To see her handwriting in the margins — the felt-tip loops, the exclamation marks — all as distinctive as her voice — brought back the same sharp hit of joy I’d felt as her student.

“Have you established that you’ll be writing about LA Society?”

“Can you see that from a car?”

“You write extremely well.”

At the very bottom of the last page, she inscribed: “I don’t think this 'ends.' Or are you just halfway through? Anyway what you do have here is absolutely swell.”

Between the lines she’s saying: “Keep going.” She always has. It’s an echo, I now realize, I’ve long been carrying and will continue to carry, in her voice, always.

¤

TO CAROLYN SEE, by Laurence Goldstein

Now you’re gazing downward,

taking notes, as angels do,

even of inessentials. Rid

of all the macula of time

and worldly ambition, but

attentive as ever, you preside

and, I imagine, still cultivate

our kind, like those boys on

Wilshire Boulevard that your coven

of giggly teens vamped on

during golden glamorous days

in your favorite flesh. Or so you wrote.

“Write about what’s physical.

Write about sex,” you told my frosh

comp class in 1960, “and wait

awhile before you fall for French

styles and settings. Choose L.A.

as your hard turf. Like I do.”

Take down this note. You were

indispensable to the happiness

so many well-wrought characters:

your mean mother and hardy dad,

your splendid daughters and dear John.

You made even ghosts immortal.

Or so it seems on this summer day

when drought imperils the sites

of your fiction — gardens and Gardens,

canyons, Chinatown, the surf-

foam rising upward like your soul.

Like your voice. Your sentences.

Indignation with urban life

keeps your vision up-to-date.

True, the last poor beach is buried

in dollars, Dashiell Hammett

and Henry Miller go untaught,

traffic saps our will to voyage out.

But your tensile prose survives,

reprinted just as stores demand.

See how we read it. Overhear us

parse your paragraphs. You knew

we would never stop loving what

you made essential to our lives.

We’ll keep thanking you, placing you

aloft in the second-best perch

L.A. has to offer, its blue tomorrows.

¤

Eulogy by Jonathan Kirsch

I want to start by acknowledging to Clara and Lisa that they have always had to share their beloved mother with her readers, and never more so than at this sad and painful moment. Ann and I want to express our gratitude to Clara and Lisa and their families for allowing us to participate in today’s tribute.

A passion for Van Morrison is something that Carolyn and I shared and talked about a lot. He was the source of powerful if subliminal inspiration for both of us, but Carolyn also told me, for example, that she met a masseuse who once had Van the Man on her table and, Carolyn confided that he was not very gentlemanly.

When I heard the sad news about Carolyn’s death, I put one of Van’s songs, Comfort You, on the box. Carolyn and I had talked about that song, too, and what I recall is a story she told me about how the song soothed her during a bad acid trip in the Muir Woods back in the day.

Here’s how the song goes:

Just let your tears run wild

Like when you were a child.

I’ll do what I can do.

I just wanna comfort you.

I can witness to the fact that Carolyn was always a source of comfort. More to the point, however, she comforted the afflicted and afflicted the comfortable.

She was always radiant and serene, generous and funny, and yet, as she reveals so bluntly in Dreaming, she is neither shocked nor embarrassed about the darker side of human nature and experience. To put it another way, the fact that Van Morrison may get a little frisky on the massage table does not detract from the artistry of his words and music or diminish the inspiration that she drew from it.

As I wrote in the Los Angeles Times when she won a lifetime achievement award named after my late father:

See is always capable of surprising us, and she stubbornly refuses to be consigned to any of the niches reserved for women who write. She is not a “women's novelist” or a “feminist” novelist or even a “California” novelist. Rather, she is unmistakably herself, a voice so distinctive and so authentic that her every word crackles with good humor and sings out with sheer joy.

That joy and humor always carried an edge. When Dreaming was published, both of us participated in a book-and-author program along with a prominent rabbi who had written an inspirational book about God. To demonstrate how one ought to believe in something we cannot see or hear or feel, he summoned Carolyn from her seat on the stage and asked her to stand directly in front of him. “I love my wife,” he said. “I love my daughters.” And then he commanded Carolyn to reach out and, as he put it, “Touch my love!”

I don’t think the good rabbi quite realized that Carolyn, both as an English professor and as the daughter of a prolific author of erotica, might regard his words as metaphorical rather than theological.

I saw a twinkle in Carolyn’s eye as she reached out for the rabbi with both hands. A titter ran through the audience. Then, at the last moment before moral catastrophe, she raised her hands and vaguely outlined the rabbi’s head and shoulders. A scandal was averted, but the point was made. Carolyn would not abide sanctimony, and especially when it concealed a hard truth.

In 1994, on the occasion of Carolyn’s 60th birthday, I borrowed a line from Golden Days to create a postcard in her honor. It is a passage that I have quoted over and over again across the years because I can always hear Carolyn’s authentic voice in her words. How could I have known then that it would provide a eulogy for its author?

Here’s what Carolyn wrote:

Some say Lorna was a quack. Could that have been what they said? But I say she was magic, because I took all of it, the part I couldn’t bear, that little lost dog, that running jump of love, my dead souls, all souls, and my beloved dearest daughters, wrapped them first in white light, then in pink, and floated them away to be a star.

So I want to echo Carolyn’s own words today. I say you are magic, Carolyn, and now more than ever before. You’ve made that running jump of love, and you have floated away to be a star.

¤

Transcription of John Rechy's Note

For Carolyn: Jul 21, 2016

In old Hollywood, there was a small contraption known as a “key light.” Only the greatest actresses — and only actresses — were given it; a unique light for each. It cast a glow that allowed the star to be seen at her best.

Carolyn had her own key light, but it was not a contraption. Hers was an inner key light, and it radiated from her presence, uniquely hers. Its magic, shimmering spirit is in every book, everything she wrote. It was in her celebrated teachings that inspired so many writers. It was certainly in her many friendships, cherished by everyone who felt such friendship as if it were only for him, for her — special. Her inner key light, her spirit, her magic — how else to account for the fact that she could smile while she was crying?

There’s another metaphor I might use to try to share my feelings about Carolyn. I’ve heard that some plants — perhaps all plants, perhaps only the most beautiful flowers — I think of peach-colored roses — when they are separated from their roots, that those plants, those flowers, those peach-colored roses flecked with red, leave an aura, a magical outline that lingers after they have been separated. Carolyn surely has left such an aura that those of us who cherish her will detect in memories of her.

How best to end these loving notes to someone special than with her own words: Dear Carolyn, there will never be another you.

— John Rechy

¤

LARB Contributors

John Francis Rechy is an American author. He is the recipient of PEN Center USA’s Lifetime Achievement Award and The Publishing Triangle’s William Whitehead Award for Lifetime Achievement. Among the pioneers of modern LGBT literature, Rechy is the author of over a dozen novels, nonfiction books, and plays, and has written essays for The Nation, Los Angeles Times Book Review, Washington Post Book World, The Saturday Review, New York Times Book Review, San Francisco Chronicle, The Philadelphia Inquirer, Dallas Morning News, London Magazine, Evergreen Review, New York Magazine, The Advocate, Mother Jones, Premiere, and many other national publications.

Susan Straight is Distinguished Professor of Creative Writing at University of California, Riverside. Her latest novel is Between Heaven and Here.

Jonathan Kirsch, author and publishing attorney, is the book editor of the Jewish Journal. He is the author of, most recently, The Short, Strange Life of Herschel Grynszpan: A Boy Avenger, a Nazi Diplomat and a Murder in Paris (Liveright).

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!