About a Girl

By Susan ZiegerDecember 22, 2015

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

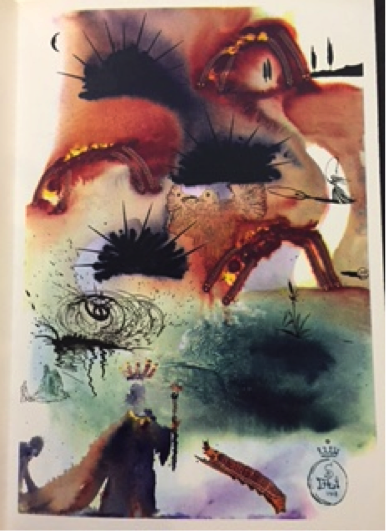

THE COUNTERCULTURE claimed Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland right around the time of its 100th birthday in 1965, when young people re-interpreted the book’s 19th-century fantasy of disorder as a trope for altered mental states. At the time, Lewis Carroll’s jubilant celebration of chaos seemed to have been in waiting to become a subversive rallying point — most famously by Grace Slick; her 1965 song “White Rabbit” referenced not only Carroll but also Owsley Stanley, the chemist known by that moniker, who provided the musicians of the day with LSD. Carroll’s imagery was in a sense re-claimed by supreme Surrealist Salvador Dalí (“I do not take drugs; I am drugs”) in 1969, when Random House joined with Maecenas Press to publish a limited edition of the text with 13 electrifying Dalí compositions. Drugs or no drugs, Dalí captured the youth culture’s mixture of mad energy and entranced introspection. His images still delight and amaze today: a gargantuan rabbit with a pulsing eye leaps over a mushroom; a fiery orange tree sprouts through the center of a melting clock strewn with teacups.

Princeton University Press’s re-publication of these lavish images in an affordable format is an exquisite way to mark the 150th anniversary of Carroll’s famous story. This superb edition invites us to back to the 1860s, with a detour through the 1960s, and via psychoanalysis — unavailable to Carroll, but key to Dalí’s Surrealism. Running through these moments in history is the figure of the girl, adrift in an absurd and arbitrary world, puzzling over her own identity.

The adventuresome girl usually returns critics to the well-known problem of Carroll’s possible erotic interest in Alice Liddell, the story’s real-life inspiration. In the mid-1990s, scholars intrigued by Carroll’s photographs and drawings of semi-clothed girls, and his sudden break with the Liddell family in 1863, raised the specter of pedophilia; it has yet to be either credited or dispelled. Nor may it satisfy 21st-century readers to learn that Oxford men routinely sought the company of young girls for boating and picnics, that many English girls became engaged and married in their mid-teens, and that the age of consent changed in 1865 — from 12 to 13. In step with his milieu, Carroll drew pleasure and inspiration from his time with Alice and her sisters, Lorina and Edith. His recent biographer, Robert Douglas-Fairhurst, suggests that Carroll’s emotions toward them were “sentimental rather than sexual,” and there is some evidence for that: over Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland hangs a premonition of the loss of youth and beauty that hits a distinctive emotional note.

The fictional Alice’s plunge into a lawless world, radical physical transformations, and return to normality, also gesture faintly toward the prurience that flavors Victorian culture. In this period, middle-class women and girls who left the house unaccompanied, displayed pleasure in eating and drinking, and eschewed corsets risked their reputations. Christina Rossetti’s contemporaneous poem “Goblin Market,” which appealed to Victorian children and late 20th-century pornographers, also causes this historical whiplash. Dalí’s imagery, suffused with Freudianism and sexual permissiveness, offers an alternative both to Victorian erotic innocence and to the contemporary tendency to detect childhood sexual abuse everywhere it looks.

Dalí bypasses the question of Carroll’s attraction to girls by reinterpreting Alice as a woman through a figure that appears in each of the 12 chapter illustrations and in an etching that precedes the title page. In it, a curvaceous female figure in long skirts with flowing hair and raised arms clasps a jump rope that billows up and out in a wide loop, casting a shadow on the ground; it can be seen in the upper right quadrant of the cover illustration, “The Lobster-Quadrille.”

“The Lobster-Quadrille”

In the shadows, the rope appears to extend and fuse with Alice’s arms, encircling and transforming her into an eerie mythic being or inscrutable ancient symbol. Dalí’s Alice varies in size and placement in the composition; sometimes her hair flows, and sometimes she looks bald; and she is often angled forward, as if about to lash the ground or rush out of the picture. The rope-circle signifies a hole that she carries with her, a negative space of femininity into which Carroll’s Alice plummets in the first pages. As Mark Burstein’s introduction to the edition notes, Dalí was repeating himself, recycling the figure from paintings such as Morphological Echo (1934–6), Nostalgic Echo (1935), and Landscape with Girl Skipping Rope (1936). The only moment in the story that the figure could possibly reference is when Alice stretches her arms around the mushroom “as far as they would go, and broke off a bit of the edge with each hand,” but even this is a stretch, as Dalí substitutes rope for the mushroom. What makes this figure resonate with Carroll’s story? How does it challenge our expectations of Alice’s girlhood?

By diverging so widely from the text, and from the tradition established by John Tenniel’s original illustrations, Dalí brings to the surface the narrative’s mingled melancholy and latent eroticism. Evoking Carroll’s penchant for reversing expectations, Dalí begins at the story’s end, in which Alice’s older sister imagines her as an adult: “[S]he pictured to herself how this same little sister of hers would, in the after-time, be herself a grown woman; and how she would keep, through all her riper years, the simple and loving heart of her childhood.” In these saccharine moments, the story nudges its readers back to drab reality by italicizing the apparent inevitability of the human female’s biological life cycle from pubescence to maturity.

Throughout the narrative, Alice has magically violated this sequence by growing instantly to gigantic proportions and shrinking to the size of a mouse. Trying to convince the Pigeon that she is not a serpent in spite of her elongated neck, she gives a dubious account of herself: “‘I – I’m a little girl,’ said Alice, rather doubtfully, as she remembered the number of changes she had gone through that day.” The marvel of wonderland lies as much in Alice’s physical elasticity as in the array of talking animals and the aristocrats’ bizarre irrationalism. The same spirit of play led Carroll to photograph Liddell as a beggar and a princess. In his vision, the girl is an endless, exuberant possibility until time and nature make her into a woman. Weighed down by voluminous Victorian skirts and hair, Dalí’s static, haunted figure never completes her rope-skip. Each of his illustrations evince an adult Alice pining for her lost childhood, a jumbled memory-scape of saturated color and outsized and miniaturized forms.

Though we may recall the story as amusingly punchy, it is also riven with sadness. “Mine is a long and a sad tale!” declares the Mouse, though we and Alice are distracted from its plot and emotion by the punning typeface that emulates a tail slinking down the page. Similarly, the Mock Turtle, “sitting sad and lonely on a little ledge of rock […] sighing as if his heart would break,” narrates his existential crisis — he once was a real turtle — but this confession dissipates into puns about the Tortoise who “taught us.” As early as chapter two, Alice sheds “gallons of tears, until there was a huge pool around her, about four inches deep and reaching half down the hall.” Carroll’s exaggeration transforms her misery into humor, diverting attention by zipping the plot along, but the story never directly addresses the motif of misery.

Dalí realizes both the dreamlike fragmentation of Carroll’s broken-off narratives and the evident gloom of all the creatures who fail to communicate or produce anything. Viewers of conventional, horizontal landscapes expect figures to travel across the space and thus sequentially through time, but the vertical landscapes of Dalí’s wonderland suggest instead the layered mind of psychoanalysis, in which unconscious forces and memories erupt upward, and consciousness exerts the downward pressure of repression. Dalí’s mock turtle, his shell aflame with yellow, is haunted from below by the primitive memory of his former self, and from above, inexplicably, by a butterfly exploding into human figures, while Alice jumps rope with her shadow in a corner. In one particularly sinuous image, Alice’s pink arm lolls from a second-story window to the ground, where it gingerly pinches a butterfly.

Dalí’s distinctive visual idiom is clearly indebted to Sigmund Freud, in particular his Interpretation of Dreams (1900), which Dalí considered one of the “great discoveries” of his life. Keen to paint dreams, he developed a mental practice of entrancing himself, and attempted to reproduce his visions on his canvases, which he stocked with his own personal symbols as well as with the keys and candles of classical psychoanalysis. Freud was the engine of Surrealism, and Dalí’s fellow travelers André Breton, René Magritte, and Man Ray also celebrated the unconscious as an authentic, individualized rebellion against externally imposed, rational controls. Dalí finally met and sketched Freud a year before the great thinker died in 1939.

“The Rabbit Sends in a Little Bill”

As with most psychoanalytically inflected, man-made art, Dalí’s image is also ripe for feminist reinterpretation. Too vivid and alive for stuffy feminine domesticity, the woman in the illustration longs to break her confines, stretching down — and back — to her girlhood. Yet she remains indoors, hidden behind high windows, Spanish tiles, and an improbably long staircase on which a caterpillar crawls. The image stews with the lugubriousness of 1960s psychedelia — one that also speaks to second-wave feminism.

The 1960s appropriated Alice’s Adventures with both insight and error. When Grace Slick recorded “White Rabbit” with Jefferson Airplane in 1967, a stately but ominous bolero powered by otherworldly vocals, the song popularized the notion that Alice’s physical changes were really the perceptual distortions of hallucinogenic experience. Books such as Alice in Acidland (1970) and Go Ask Alice (1971), as well as Disney’s sly 1974 re-release of its 1951 animated film Alice in Wonderland for mind-altered viewing, cemented the association with psychedelic experience. To the youth culture, Carroll’s text seemed serendipitously full of drug references. The King reads “Rule Forty-Two” from his notebook: “All persons more than a mile high to leave the court. Everybody looked at Alice. ‘I’m not a mile high,’ said Alice. ‘You are,’ said the King. ‘Nearly two miles high,’ added the Queen.”

Carroll himself, however, did not eat magic mushrooms. Although opium — in fearsome doses — was associated with visions since Thomas De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1821), Victorians did not experience anything remotely psychedelic until the 1890s, when Silas Weir Mitchell, Havelock Ellis, and other researchers began self-experimenting with mescaline and peyote. Carroll was mocking didactic literature for children, which Alice recalls when deliberating about whether to experiment with the bottle labelled “Drink me”: “She had read several nice little stories about children who had got burnt, and eaten up by wild beasts, and other unpleasant things, all because they would not remember the simple rules their friends had taught them.” Such examples of children’s literature before Alice’s Adventures remind us of the grim child death rate in the 19th century and the refreshing freedom from it that the Alice books purveyed. Thus, Alice did not so much represent a perceptual distortion of reality as whimsically indulge a little girl’s point of view, with its curiosity, partial education, self-centeredness, and desire for sweets. Carroll’s imaginative sympathy counted as a proto-feminist gesture. The 1960s’ psychonautical version of Alice also tacitly endorsed feminist mental adventuring: before that, representations and accounts of women’s mind-altered experience could be counted on one hand.

Carroll may have seemed to the counterculture like a Victorian version of R. D. Laing or Timothy Leary, reinterpreting Enlightenment reason and modern power as insanity, but this impression was also wrong. Carroll was fully committed to the dominant paradigms that his text later seemed to upend. An Oxford don, he taught mathematics; he also served as a deacon of the Church of England. Rather than political and cultural critique, Carroll saw harmless fun. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass seemed natural extensions of the comic family newspapers he had made for his 10 brothers and sisters, or the brain teasers he invented to entertain his mathematics pupils. If he had a specific axe to grind, it was a mathematical one.

At first glance, Alice’s Adventures seems to pit the arbitrary rules of language and social custom against those of logic and geometry. When Alice proclaims that saying what she means is the same thing as meaning what she says, the Hatter, March Hare, and the Dormouse contradict her with examples that expose language’s density in comparison to reversible mathematical sentences: “‘Why, you might just as well say that ‘I see what I eat’ is the same thing as “I eat what I see’!” Likewise, when the Tortoise explains that his school lessons began at 10 hours a day and “lessened” by an hour each day, with a holiday on the 11th, Alice asks, “’And how did you manage on the twelfth?” to which the Gryphon replies, “‘That’s enough about lessons.’” Such jokes perform Carroll’s antipathy to negative numbers, which, along with imaginary numbers and the multiplication of lines by lines, constituted the new trend of symbolic algebra. Carroll was a mathematical literalist, preferring logic and geometry for their referential relationship to reality, and thus, absolute truth. Accordingly, Alice’s Adventures mocks the resulting unreal wonderland, ungoverned by Euclidean geometry and real numbers, as much as it seems to celebrate it. Carroll’s mathematical conservatism makes his vision somewhat less subversive than 1960s popular culture would have it. On the stability of a mathematized world, Carroll and Dalí have little in common, so the inclusion of a preface by the differential geometrician Thomas Banchoff fits uneasily in the volume. Banchoff details his dealings with Dalí in the 1970s, when the artist consulted him on hyper-cubes in his efforts to render stereoscopic effects, which do not appear in the Alice images.

Although mistaken about Carroll’s taking drugs and questioning reality, the counterculture accurately observed the text’s idiom of challenging the illogical. Mirroring the youth movement, the Alice figure innocently questioned authority, custom, reality, and even herself, exposing hypocrisy and nonsense. Marshall McLuhan and Quentin Fiore’s contemporaneous collaboration of word and image, The Medium is the Massage (1967), echoed Carroll in a minor key: “Today’s child is growing up absurd, because he lives in two worlds, and neither of them inclines him to grow up.” McLuhan’s two worlds were the vestigial 19th-century world of authoritarian, conformist education, and the heady phantasmagoria of mass media and other kinds of consumption. The original Alice also inhabited similarly inadequate, polarized worlds of discipline and sweets; wonderland, where she could literally grow up but not mature, combined them. McLuhan’s universalizing masculine pronoun aside, in Alice, the little girl becomes the relentless interrogator and affirmer of biological, perceptual, and mathematical order. This questioning is everything. The girl has only a brief time to do it before she becomes weighed down in crinoline and immured by adult concerns. Little girls — traditionally more docile students than boys — have learned just enough to ask the pointed question but lack the brashness or rage to overthrow the classroom. Carroll’s narrative allows her to wonder aloud throughout, until she is coaxed into a sleep from which she awakens as a rueful woman: Dalí’s tragic, nostalgic figure, whose upraised hands, or fists, are ingeniously bound together. On the sesquicentennial of Carroll’s story, Alice remains vaguely countercultural, obscurely intellectual, somewhat feminist — and absolutely vital to modern culture.

¤

LARB Contributor

Susan Zieger is a scholar of 19th-century British and related literatures, with a special interest in the novel and mass culture. She is the author of Inventing the Addict: Drugs, Race, and Sexuality in Nineteenth-Century British and American Literature (University of Massachusetts Press). She teaches at the University of California, Riverside.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Scenes from the Resistance: Georges Perec’s “La boutique obscure”

GEORGES PEREC'S dream journal, which he kept between 1968 and 1972 and published in 1973 as La boutique obscure, is bookended by two dreams about...

Outsider Theorist Paul Scheerbart

IN THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING WORLD, perhaps the only traces of the phantasmagoric novels of German critic, serialist, and outsider theorist Paul Scheerbart...

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!